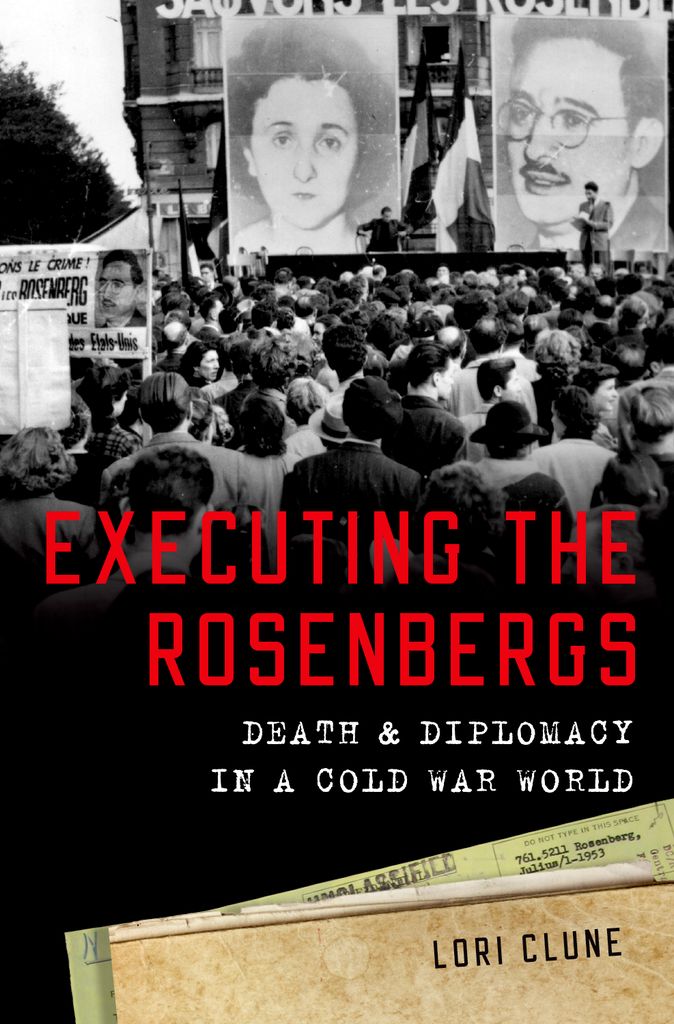

Executing the Rosenbergs

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clune, Lori, author.

Title: Executing the Rosenbergs : death and diplomacy in a Cold War world / Lori Clune.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015040550 | ISBN 9780190265885 (hardback) | eISBN 9780190265908

Subjects: LCSH: Rosenberg, Julius, 19181953Trials, litigation, etc. | Rosenberg, Ethel, 19151953Trials, litigation, etc. | Trials (Espionage)New York (State)New York. | Trials (Conspiracy)New York (State)New York. | United StatesHistory1945-1953. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century.

Classification: LCC KF224.R6 C58 2016 | DDC 345.73/0231dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040550

Portions of .

To the memory of Anthony Salvatore Scimeca

CONTENTS

My research into the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg began as a minor detour. I was writingor thought I was writinga book about international perception of various high-profile Cold War security cases. Singer Paul Robeson, actor Charlie Chaplin, Senator Joseph McCarthy, atomic scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer: they were the main subjects of my investigations. It was their cases that led me to the State Department archives when I discovered the perplexing case of the missing Name Cards.

Whenever an American diplomat abroad reports back to Washington, D.C., the State Department keeps a record of the communication. In the 1950s, when a Foreign Service officer stationed overseas wrote to the State Department in Washington, officials labeled and catalogued the correspondence and created a Name Card for anyone referenced in the message. Though sometimes problematic in terms of objectivity and translation accuracy, these diplomatic communications included foreign policy considerations and sensitivities that were carefully considered back in Washington.

Diplomats sent dispatches from their posts to alert Washington of issues and controversies, often asking for clarification or guidance, and occasionally offering policy suggestions. The resulting Name Card Index consists of hundreds of boxes packed with thousands of tissue-thin pieces of three-by-five paper. Each of these cards contains cross-referenced document numbers and is alphabetized under the last name of everyone mentioned in the communication. This index is indispensable for researchers delving into State Department Cold War documents.

For example, in the State Department Name Card Index for 19501954, located in National Archives II in College Park, Maryland, there are more than fifty Name Cards for Senator Joseph McCarthy.case of Charlie Chaplin garnered international attention, prompting a handful of Name Cards. When the State Department rescinded J. Robert Oppenheimers security clearance, a half a dozen Name Cards resulted. Paul Robeson and his suspended passport generated about twenty Name Cards.

The case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had attracted even more international attention than those of Chaplin and Robeson. FBI agents arrested thirty-two-year-old Julius Rosenberg in New York City in 1950 and officially charged him with conspiracy under the Espionage Act of 1917. Specifically, officials accused Julius of using his military spy ring to pass the secret of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. A few weeks later, agents arrested his wife, Ethel. The Communist Party members claimed their innocence and refused to name names; they were convicted and sentenced to death. Appeals and protests lasted more than two years before their grisly executions in 1953 made orphans of their two young sons. In 2008, Rosenberg codefendant Morton Sobell (who had served eighteen years in prison) admitted that he and Julius had indeed passed military secrets to the Soviet Union.

As I continued my research, I decided to look at the State Department documents on the international response to the Rosenberg case. Historians had told small pieces of the overseas reaction, but I was hoping there was more. I was confident that diplomatic officials stationed overseas wrote at least a handful of telegrams concerning the Rosenberg case. So I looked for Julius and Ethels Name Cards. There were none.

As I thumbed through the Name Card Index for 19501954, I discovered it jumped from Rosenberg, Bertha to Rosenberg, Ludwig.

Historians frequently cite one particular document describing foreign protest over the executions: Ambassador to France C. Douglas Dillons May 1953 telegram to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Since Secretary Dulles forwarded this cable to the White House, a copy can be found in the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas.

Map 1 World Protest MapEmbassies, Consulates, and Legations that Documented Rosenberg Case Protest to the State Department, 19521954. Courtesy of Ben Emerzian.

A few weeks after my visit to the National Archives in College Park, archivist David Pfeiffer wrote to say that after conducting additional searches in areas where the documents could have been, he had located two boxes. He thought it looked like very good material, but the boxes had not been referenced in the Name Card Index and had never been seen before. I was excited but cautious; I knew that two boxes could mean just a few files and only a handful of documents. Stuck in California at the start of a semester of teaching, I asked my Maryland-based sister if she would consider spending an hour or so taking digital photos of the documents in College Park. She graciously agreed. An hour turned into fifteen, and as the deluge of digital documents flooded my inbox, I knew David Pfeiffer had found the treasure chest full of gold. More than nine hundred gold pieces, actually.

These boxes contain newly unearthed documents from more than eighty cities in forty-eight countries around the world: newspaper clippings, editorial comments, petitions, and placards, all attached to detailed correspondence from embassies, consulates, and legations, spanning 1952 to 1954. They show that protests extended from Argentina to Australia, from Iceland to India, and from Switzerland to South Africa (). These documents prove that the May 1953 Dillon memo was far from unique; on nearly a dozen separate occasions the American ambassador to France himself wrote to complain about the governments handling of the Rosenberg case.