BETWEEN CONTAINMENT AND ROLLBACK

THE UNITED STATES AND THE COLD WAR IN GERMANY

Christian F. Ostermann

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2021 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ostermann, Christian F., author.

Title: Between containment and rollback : the United States and the Cold War in Germany / Christian F. Ostermann.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2021 | Series: Cold war international history project | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019051240 (print) | LCCN 2019051241 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503606784 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503607637 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cold War. | United StatesForeign relationsGermany (East) | Germany (East)Foreign relationsUnited States. | United StatesForeign relations1945-1953. | GermanyForeign relations1945- | Germany (East)History.

Classification: LCC E183.8.G3 O83 2019 (print) | LCC E183.8.G3 (ebook) | DDC 327.73043/109045dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051240

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019051241

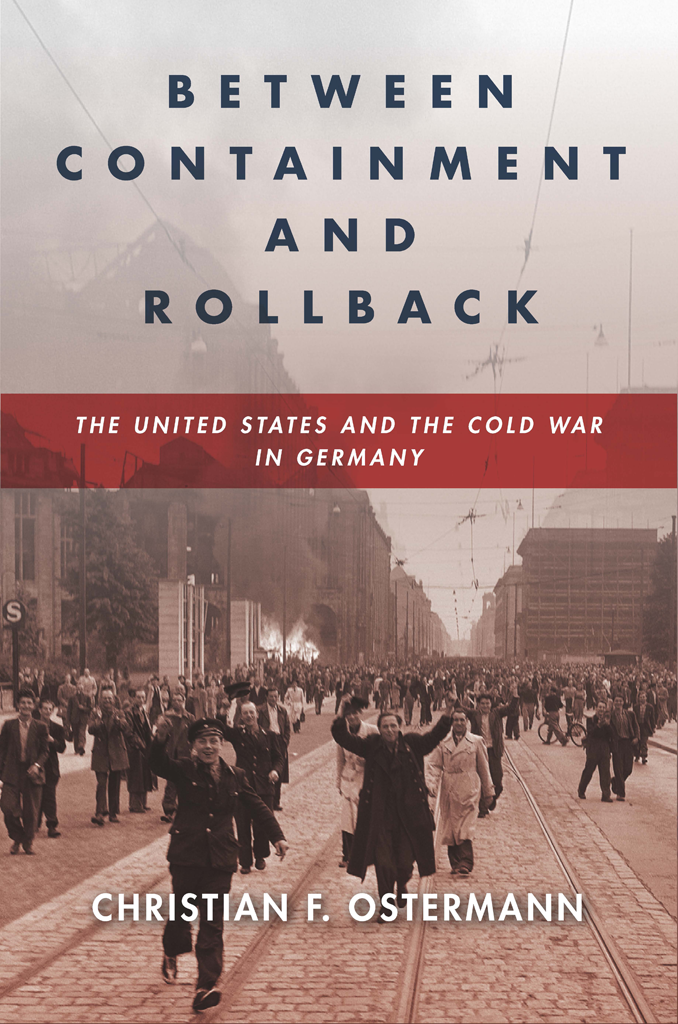

Cover photo: June 17, 1953 Uprisingstrikers on Leipziger Strasse on the way to Potsdamer Platz. Courtesy of Gert Schtz/Landesarchiv Berlin.

Cover design: Rob Ehle

Typeset by Kevin Barrett Kane in 10.2/14 Adobe Garamond Pro

To my parents, Elisabeth and Friedrich Ostermann

Contents

PREFACE

Writing East Germany into Cold War History

On February 9, 1990, U.S. president George H. W. Bush sat down to pen a personal letter to West German federal chancellor Helmut Kohl. He wanted Kohl to know that he wholeheartedly supported the chancellors accelerated drive toward German unification. The situation in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had been deteriorating. For many East Germans, change in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, could not come fast enough. Thousands of East Germans went west, putting pressure on Kohl for fast-track unification. The West German leader was about to confront Soviet Communist Party secretary general Mikhail Gorbachev, who, by all accounts, held the key to Germanys unity. Bush assured his German counterpart of the complete readiness of the United States to see the fulfillment of the deepest national aspirations of the German people. If events are moving faster than expected, it just means that our common goal for all these years of German unity will be realized even sooner than we had hoped.

In characterizing his support of Kohl, Bush was on the mark. Sooner than other European leaders, the American president had developed a comfort level with the idea of German unification: Id love to see Germany reunited, Bush told the Washington Times on May 16, 1989.

Yet the grand narrative of Americans and Germans standing side by side for all these years in the pursuit of Germany unity, so evocatively suggested by Bushs letter to Kohl, reduces the complex story of U.S. policy toward the German question since the end of World War II. This study looks at that storys early years, from Allied occupation to the early 1950s, when both West Germany and East Germany became members of the politico-military pacts facing off against each other in Europe. It does so through the prism of American attitudes and policy toward the Soviet-controlled part of Germany. It was these Germans, caught by the post-1945 geopolitical fallout of the war that Nazi Germany had launched in 1939, who most dearly paid the price of the countrys division. Histories of the AmericanGerman relationships in the postwar era have left these Germans largely out of the narrative. This book seeks to write the East Germansleadership and populaceback into history, certainly as objects of American policy, at times even as historical agents of their own.

Was there an American policy toward East Germany? Two major intellectual-political projects for a long time relegated the answer to this question to a footnote. One was the perception, prevailing for most of the Cold War, of the USSRs dominating role in the Soviet occupation zone and later the German Democratic Republic. In this view, generally speaking, the GDR as part of the Soviet-led eastern bloc lacked historical agency. American policy was thus directed at the Soviets in Germany; based on the supreme authority the four occupation powers had assumed in Germany in June 1945, the United States held the USSR responsible for events in the Soviet zone and GDR.. If there was a distinctive U.S. approach to East Germany in this perspective, it was one of diplomatic non-recognition of the Communist German regime after 1949, a policy that sought to deprive that regime of any legitimacy and aligned with the West German Hallstein Doctrine, which punished recognition of the GDR by other countries. During the Cold War and beyond, many historians unconsciously echoed the dominant political view in the West by denying the GDR historical agency. Not until 1989 did a book by a political scientist address the topic more fully, although it focused on

The more important reason for the lack of inquiries into U.S. policy toward East Germany was the primacy of the American relationship with its Germany. To this day, the alliance the United States forged with the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) represents one of the most successful endeavors in the history of U.S. diplomacy. Turning the western part of Germany from a wartime adversary to an economically and politically pluralistic, vibrant, and peaceful ally was and is considered critical to the postWorld War II reconstruction and stabilization of Western Europe and the global liberal-capitalist system, vital to Americas prevailing in the Cold War, and central to assuring U.S. predominance on the European continent once the Soviet empire had crumbled.

Emblematic of the importance of West Germany to the United States, President Bush in May 1989 called for both countries to become partners in leadership. With a great deal of merit, generations of historians in the United States and Germany and beyond have written libraries full of books exploring every aspect of Americas relationship with the Federal Republic. Whether supportive of the relationship in which both countries had invested so much, or critical of the mistakes, failures, and moral or political compromises that had been involved, however, these bodies of work were by and large united in their neglect of East Germany as a serious factor in forging the relationship.

This book is made possible by two recent historiographic shifts, both facilitated in part by access to declassified documents. First, a greater appreciation for the fact that U.S. foreign policy in the early phase of the Cold War was far more assertive in nature than the defensive posture implied by the notion of containment. Since the late 1940s, reactive, defensive notions of containing this new Soviet threat mixed in the political discourse in Washington with more activist and offensively conceived notions of liberation and of rollback of Soviet power. Benefiting from increased declassification of formerly secret documents in the 1980s, Melvyn Lefflers