Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The opinions and characterizations in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the US government.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

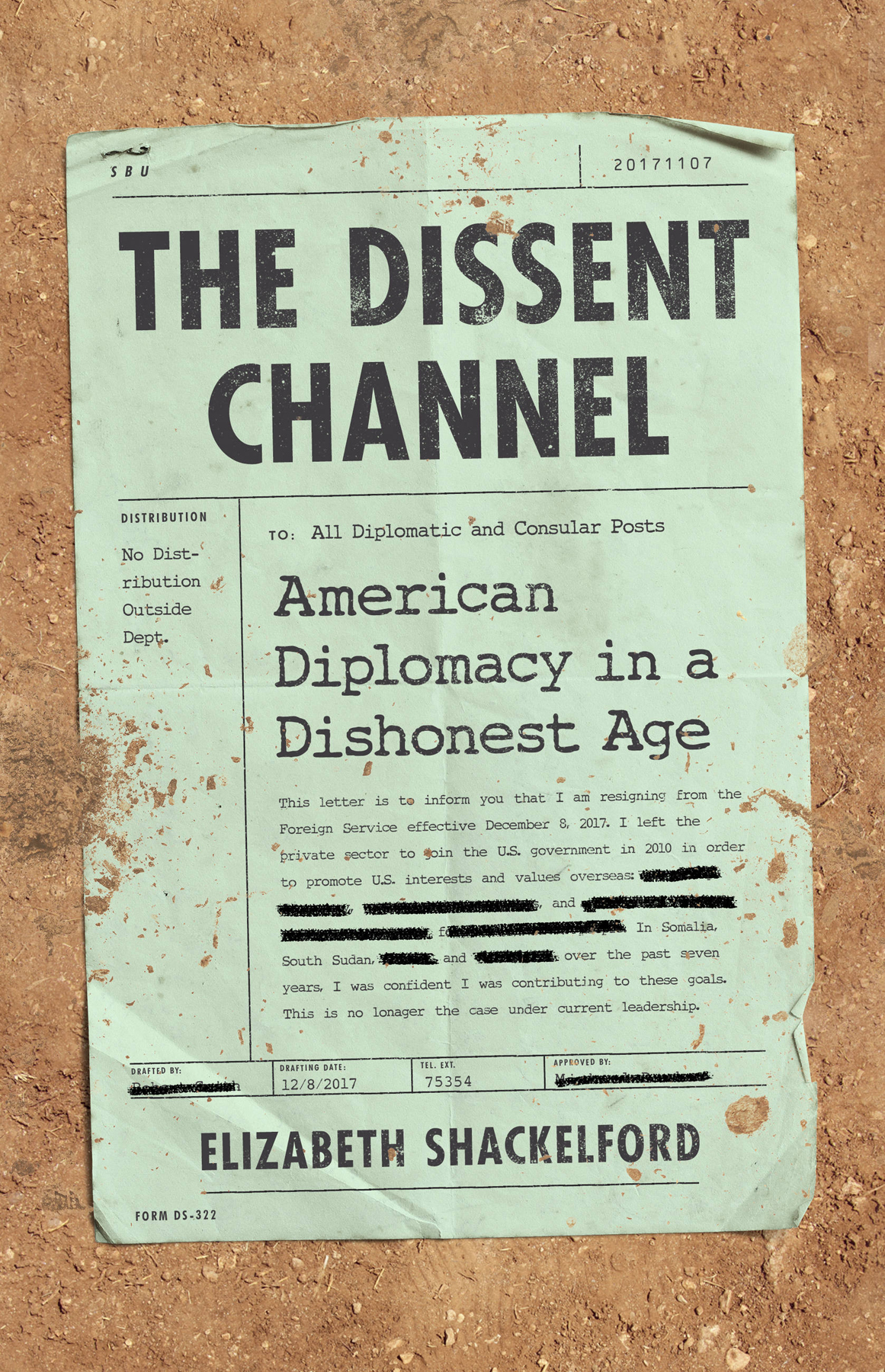

IN 1971, THE US DEPARTMENT OF STATE ESTABLISHED THE Dissent Channel, an official avenue for expressing dissent within the department. Disappointment and disgust with our foreign policy during the Vietnam War had led to hundreds of resignations, revealing unprecedented levels of professional discontent. With the White House shaping foreign policy decisions to influence narrow political goals and domestic policy ends, career diplomats felt helpless, watching a barrage of far-reaching consequences unfold. But the administration had no intention of changing its direction. The Dissent Channel was the bureaucratic solution. The Foreign Affairs Manual outlines its purpose and process:

It is Department of State policy that all U.S. citizen employees, foreign and domestic, be able to express dissenting or alternative views on substantive issues of policy, in a manner which ensures serious, high-level review and response.

It is considered an option of last resort, to be used after all other routine channels have been attempted.

In an institution staffed with polite professionals tasked with minimizing conflict and managing discord (were diplomats, after all), its use is rare. As it is a carefully guarded internal tool, its public discussion is even rarer. If youve heard of it at all, it was probably from the leaked dissent cable in 2017 opposing the Muslim travel ban, which more than one thousand State Department employees signed. Or in 2016, when a few dozen diplomats signed a dissent urging strikes against the Assad regime in Syria.

Usually, however, dissents are conducted quietly, politely, within the walls of the department, all protocols observed. Diplomats who have filed a dissent can tell themselves theyve done everything in their power that they could do.

Unfortunately, those dissents are often prescient, laying out in plain language the dangers of a foreign policy driven by inertia, domestic politics, short-term thinking, and overly narrow interpretations of the national interest. Often, these are lessons weve learned before. Dissents dont typically identify problems no one saw coming. They usually identify problems we willfully chose to ignore.

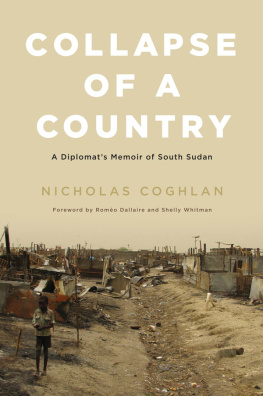

What follows is one story of a problem we ignored, repeatedly and over a long period of time, which the decisions and actions of the US government not only failed to stop, but helped precipitate. It is a story of impunity, of unchecked violence against civilians, of abuses that occurred on our watch by a government we continued to legitimize. It illuminates a long-standing American trend of failing to look at long-term consequences in our foreign policy. I learned firsthand about the consequences of our failure to take a stand for the values of human rights and justice, when doing so could make a difference. This is the story of how America failed the people of a small country and how it did so by failing itself.

This book reflects the authors best recollections and understanding of the events portrayed. While the author has had the benefit of extensive contemporaneous notes, journals, and correspondence to fact-check and enhance these recollections, others will inevitably have different memories of some of these events. Some names have been changed, some events compressed, and some dialogue re-created, but the author has endeavored at every stage to capture all events as truthfully and accurately as possible.

WITH THE FOURTEEN-HOUR FLIGHT FROM WASHINGTON behind me, I had just a short hop from Addis Ababa to Juba before Id arrive in my new home. As I sat at the crowded gate awaiting boarding, I overheard the Ethiopian check-in attendant ask a tall, thin man if he had a nationality. The question sounded odd to me, but the man took it in stride. I am South Sudanese, he responded, as an obvious matter of fact.

You only have this Sudanese passport though? asked the attendant, looking at the rough and aged travel document. How long have you been away?

Four years, the tall man replied. The attendant reflected on this for a moment and said, I cannot guarantee they will honor this and allow you in. But welcome home.

South Sudan: the worlds newest country. Many of my colleagues, friends, and family were shocked that I volunteered for the assignment, even more so that it was my top choice. I was coming out of a prime posting in Europe, which some friends had hoped might steer me away from a fixation on less glamorous places. Having left the development world behind when I joined the Foreign Service, I had options now, and a directed assignment to Europe gave me a first step on a career path winding through pleasant places to livethe kind your friends and family want to visit. No one would be visiting me in Juba. My parents werent thrilled with my choice, but they knew me better than anyone. They had tried to dissuade me from a move to South Africa when I was nineteen. When that failed, they simply came to terms with my life choices, and now they expected nothing less.

An unsourced one-page backgrounder provided in my welcome packet began with a description of Juba as a place where the only time you dont feel sweaty is 5 minutes after youve had a wash (if you have any water to wash with). The rest of the sheet read:

Climate: Mostly 100 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit

Morning air: rather dusty

Evening air: extremely dusty

Getting Around: Juba has one tarmac road built in 1972 that today consists of a patchwork of potholes. All other roads are built of other potholes, dust and layers of plastic bottles and other rubbish.

Money: Take all money you think you will need with you, since credit cards are not accepted and there are no reliable banks.

Accommodation, Food and Health: Allegedly, Juba is the 2nd most expensive city in the world. Resist the urge to convert prices, otherwise you will not buy anything. Also expect rather erratic pricing. For example, a jar of Nutella will cost you $21, but a pack of 24 cans of Carlsberg will set you back only $18.