ALSO BY H. W. BRANDS

Copyright 2018 by H. W. Brands

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Portrait of Daniel Webster by Francis Alexander (1835, oil on canvas) courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; bequest of Mrs. John Hay Whitney. All other images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Cover design by Michael J. Windsor

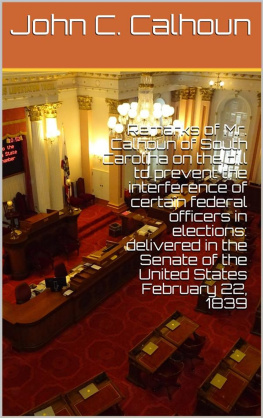

Cover paintings (details): John C. Calhoun by Arthur E. Schmalz Conrad; Daniel Webster by Adrian S. Lamb; Henry Clay by Allen Cox. Courtesy of the U.S. Senate Collection

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brands, H. W., author.

Title: Heirs of the founders : the epic rivalry of Henry Clay, John Calhoun

and Daniel Webster, the second generation of American giants /

H. W. Brands.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : Doubleday, a division of Penguin

Random House LLC, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010542 (print) | LCCN 2018030089 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780385542531 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385542548 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesPolitics and government18011815. | United StatesPolitics and government18151861. | Calhoun, John C.

(John Caldwell), 17821850. | Clay, Henry, 17771852. | Webster, Daniel,

17821852. | StatesmenUnited StatesBiography. | Constitutional historyUnited States.

Classification: LCC E338 (ebook) | LCC E338 .B73 2018 (print) |

DDC 973.5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010542

Ebook ISBN9780385542548

v5.4

ep

Contents

Prologue

JANUARY 1850

The marvelous news from the West was the last thing Henry Clay had wanted to hear. Gold! Gold in California! It set the pulse of America racing; it sent a hundred thousand brave souls to that far-off land to make their fortunes. It hastened the day when the institutions of American democracy, and not merely the American flag, would be planted on the Pacific shore. And it meant that Henry Clayaging, ailing Henry Claymust leave Ashland, his home and refuge at Lexington, Kentucky, and once more make the long journey to Washington.

Five years he had been at home. Five years he had sought and eventually found solace from ambition definitively frustrated. He would never be president. The White House would never be more than a place for him to visit. No one had come closer to its portal more often than he. No one had a better claim to the knowledge, temperament and character required of its residents. But the American people were fickle and easily swayed, and at the crucial moments they had turned from him to others.

He had learned to accept his fate. A statesman did what he could in his countrys service, not what he would. And it was for his country that he felt so dispirited by the news from California. Whatever it would cost him personallyin effort expended, health further compromised, obloquy enduredit would cost the Union more. Henry Clay had been born amid the American Revolution and come of age with the Constitution; for his entire adult life the Union had been his guiding star. Twice he had steered the Union between the Scylla of jealous states rights and the Charybdis of rampant centralism. But the turbulent seas of democracy grew more tempestuous with each passing decade. And the gold fever whipped them higher still, for the sudden peopling of California compelled Congress to rule on the fate of slavery in the new American West. California sought admission to the Union as a free state. The North demanded Californias admission, and would probably get it. What would the South demand in return? And what would the competing demands do to the creaking hull and strained rigging of the American ship of state?

The genius of Henry Clay was a knack for compromise, for finding formulas neither side loved but both sides could live with. He had conjured one such formula in the Missouri crisis of 1820, and another in the South Carolina crisis of 1833. The genius of American democracy was its ability to muddle through crisesto accept answers as tentative and let principle nod to expedience. Henry Clay had been criticized for pliant principles, but he pleaded the higher aim of preserving the Union, the guarantor of American democracy. Democracy was a work in progress, never perfect but never finished. Given time, democracy would find a way forward.

Californias gold meant democracy might not have time. With everyone else, Henry Clay had supposed that filling the territories acquired from Mexico in the recent war would take decades. The Louisiana territory had been American for half a century and wasnt a tenth full. Clay, though a slaveholder, was an emancipationist at heart: he judged slavery a curse and looked to the day when the Southern economy would outgrow slavery, as the Northern economy had done. A few decades, no more time than had already passed since the Missouri Compromise, was all that was needed.

Clay knew he didnt have a few decades. He would be lucky to last a few years. But if he could somehow conjure another compromise, he might give the Union the time it required.

J OHN C . C ALHOUN had less time than Henry Clay. His consumptiontuberculosiswas more advanced than Clays. He might have months; he might have weeks. Some days he couldnt get out of bed. His voice, for decades the trumpet of the South, could barely rise above a whisper.

Upon the news from California, his thoughts turned to Henry Clay. The two had entered the House of Representatives together amid the troubles that sparked the War of 1812. For years they had worked in harness, defending and bolstering the country their generation had inherited from Americas founders. But ambition drove them apart, like sons contesting control of an estate they were supposed to share. Clay was the elder, in years and seniority, yet Calhoun had gifts of intellect and guile Clay couldnt match. It was the guile that surprised most people, including Clay, who puzzled at Calhouns ability to advance himselfand get past Claywithout appearing to try.

But it was the intellect that brought Calhoun down. Or maybe it was the ambition, disguised as intellect. Calhouns political strength was his base in South Carolina, yet his strength was also his weakness. Other states insisted on what they considered their sovereign rights vis--vis the national government, but none were so vigilant and quick to take offense as South Carolina. The founders had left deliberately vague where the boundary lay between state and national authority; similarly blurred was who would determine the boundary and how it would be enforced. They knew that any explicit answer might wreck their experiment in self-government before it got fairly started; they left to their heirs to find a solution the country could live with. The task had been the work of Calhounsand Clayslifetime.