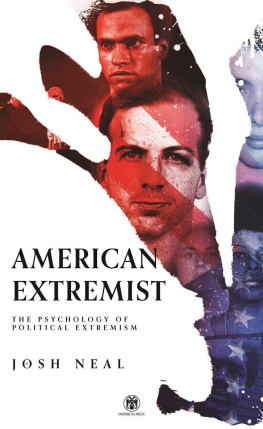

Despite their relatively mainstream, middle class existence, Micah Johnson, Muhammad Abdulazeez, and Dylann Roof were closer to extremism than most people suspected. This was not, however, because of some previously unknown revelation about their lives, but simply because everybody is. The idea that there is a firm barrier between any one person and an alternate, extremist version of them is a misconception. There is no us and them. It is an uncomfortable reality, but understanding that one fact is critical to understanding how extremism operates.

Radicalization, meaning the process by which any normal person becomes an extremist, is complex, but it has two primary components. The first elements are internal, the backgrounds, individual traits, and psychology that make up personalities. Within everybody, an internal battle exists between destabilizing factors, like drug abuse or anger, and grounding inhibitors, such as strong personal relationships or patience. Imagine this ongoing conflict as a kind of personal safety net. Destabilizers, such as ignorance, bias, stubbornness, rebellion, alienation, grievance, and isolation, fray and weaken the net. Curiosity about other belief systems resulting from destabilizing influences can also cause deterioration. Inhibitorscareers, faith, family ties, education, and social networksincrease the net's thickness, strength, and flexibility.

Everyone moves through an unpredictable world, but each navigates it with different equipment. Faced with, say, the stress of losing a house or job or the trauma of losing a loved one, everyone reacts differently. Some people become angry, others depressed, while still others hold themselves together much better. In general terms, the more grounding inhibitors that exist, the stronger the network support and the better the chance of dealing with stress healthily. The weaker the net, the more likely people are to seek revenge, sink into depression, commit suicideor be sucked into an extremist universe.

The second element of the radicalization process is exposure to external radicalizing forces, such as leaders, ideologies, conspiracy theories, social groups, propaganda, and personal relationships. There's nothing resembling an exact calculus on how the process plays out but, generally speaking, people with weakened safety nets who come into contact with extremist rhetoric and ideology are most likely to accept or latch onto extremist ideas. This is the initial step in the radicalization process.

Simply by being human in a world full of extremist ideologies and theories, everyone is possibly capable of radicalization, the process of becoming what we call an extremist. As the 1993 documentary Skinheads USA: Soldiers of Hate so forcefully reveals, the genius of William E. Davidson, better known as Bill Riccio, was to lure in boys whose safety nets were already tattered.

An infamous former Klan leader, Riccio was best known for bringing the neo-Nazi movement that flourished during the 1980s in the inland Pacific Northwest to the South. He set up his WAR house, short for White Aryan Resistance, on a compound tucked away in the woods southeast of Birmingham, Alabama. It served as a crash pad, clubhouse, and recruitment center for teenage boys eager to escape their own lives. Skinheads USA portrays these boys shouting Sieg Heil! while watching a hardcore band and giddily shaving each other's heads in the bathroom. Late at night, they ruminate drunkenly on a 1930s Nazi propaganda video: Everyone had jobs, one kid explains to the camera. Our government had to fuck it upI really wish [Hitler] had won.

WAR house may seem like a summer camp for malcontents, but it soon became clear why these boys ended up as Riccio's acolytes. Many came from broken homes, places where they were physically and emotionally abused. Few excelled at school; many had dropped out. Some of the teenagers had been in trouble with the law. Drug and alcohol addiction were common. When Riccio tells the camera, We want the broken it's nonclinical language describing kids with active destabilizersanger, ignorance, crisis, alienation, isolationand often virtually no grounding inhibitors, including family ties, faith, education, future goals, and social networks.

At WAR house, the boys found the community they desperately needed, but it was intertwined with a vicious extremist ideology. So, they began down the path of radicalization, not because they had a strong desire to resurrect Hitler's agenda in 1990s Alabama, but it was impossible for them to separate the rewards of the social network without Riccio's rhetoric. Being a neo-Nazi skinhead was, in fact, what bound them. At WAR house, White Power was a greeting and space filler in conversations. Throughout Skinheads USA, the boys have almost nothing to hold on to, other than the ideology that Riccio has offered.

Riccio sought out angry, adrift youth because they were the most likely to buy into his celebration of Hitler in a country where Nazis are usually shorthand for evil. But there was likely a secondary reason he was seeking out broken toys. In one scene in the documentary, Riccio prays to Odin to protect his youth, but in recent years, several former WAR house residents came forward to report multiple cases of sexual abuse.

Ronnie Painter, then a fifteen-year-old alcoholic addicted to painkillers when he met Riccio, told authorities he fled to WAR house to get away from his mother's physically abusive boyfriend, but his escape was short-lived. Painter said that Riccio had sexually exploited him at least four times while he lived under his roof. I'd get extremely drunk and ride off in the car with him; then he'd perform oral sex on me. His brother, Lonnie, told a similar story.

This is not to suggest that all recruiters for white supremacyor other types of extremismare sexual predators. But it does serve to highlight how much the two groups share in common in terms of targeting and recruitment techniques. Both look for young people in need of love and attention. Both know that it's much easier to groom a child who has a missing or abusive parent. Both frequent places like playgrounds, parks, malls, arcades, and sports fields. Undeterred by the allegations against As repugnant as the neo-Nazi ideology embraced by the teenagers was, they were also victims.

Do the activities at a neo-Nazi compound in the 1990s have anything in common with the possible radicalization of Micah Johnson, Muhammad Abdulazeez, and Dylann Roof? On the surface, perhaps not much is similar. Roof and Abdulazeez both abused alcohol and drugs, but none of the three were runaways, belonged to any extremist social groups, had shaved heads or any other telltale extremist appearance. However, digging a little deeper reveals fraying inhibitions and growing destabilization.

Inspired by his high school Junior ROTC experience, Johnson had been excited to serve his country when he shipped off to Afghanistan with his engineering unit in 2013. He had a bunch of friends in his unit, including a girl he'd had a crush on since high school. They weren't a couple, but she and Johnson had been close for years. She bought his mom, Delphine, presents on her birthday and Christmas, and had spent the night at the Johnson household several times.

In Afghanistan, though, things fell apart in short order. From the beginning, Johnson was traumatized by the daily explosion of mortar shells. Then Johnson's crush got involved with an officer, and he angrily confronted her. Soon afterward, Johnson was caught in possession of a pair of her underwear that he'd stolen from the laundry. A search of his room found illegal weapons.

As a result, Johnson's army-issued gun was taken away, and he was put under twenty-four-hour escort before being discharged and sent home. Johnson's military lawyer suggested the punishment was unusually harshnormally soldiers would be sent to counseling for such a first-time offensebut for whatever reasons, his plea fell on deaf ears.

Next page