Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen

Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Julia Bosson: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Political extremism: how fringe groups operate / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823158 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823141 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823165 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Radicalism United StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. | Right and left (Political science)Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC HN90.R3 P65 2020 | DDC 303.484dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

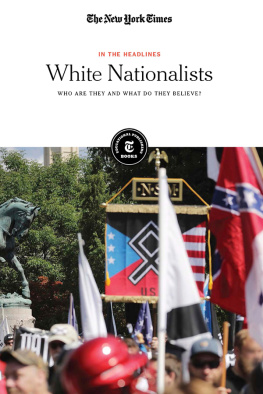

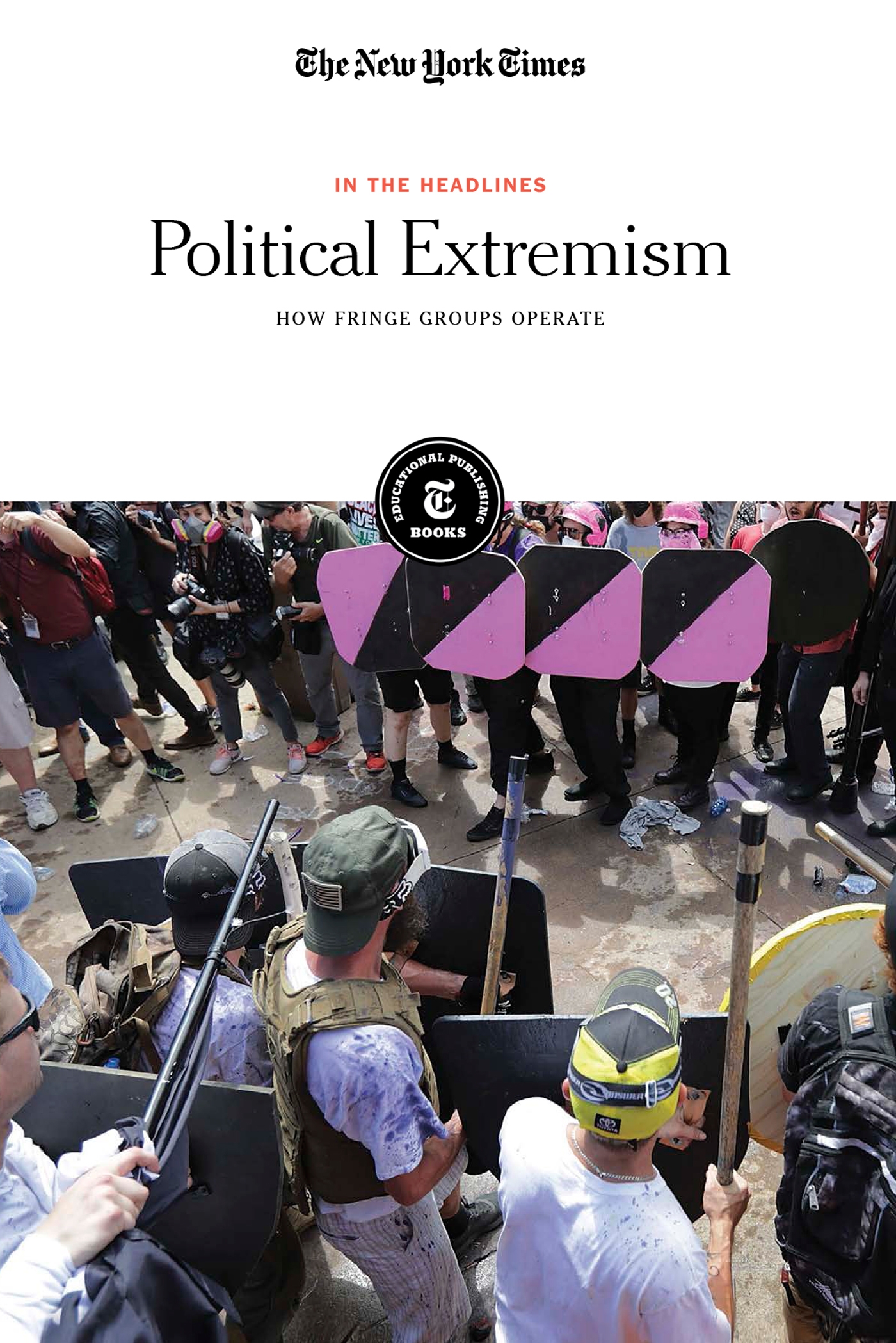

On the cover: Battle lines form between white nationalists, neo-Nazis and members of the alt-right and anti-fascist counterprotesters at the entrance to Emancipation Park during the Unite the Right rally, Aug. 12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Va.; Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Contents

Introduction

AMERICA IS UNDER threat from extremists. But depending on your political beliefs, it might come as a surprise to learn that more people have been killed by far-right and white nationalist extremists than Islamic radicals since 2001. When most people think of extremists, the first things that come to mind might be religious extremists, particularly those who have brought their beliefs toward violent ends. But extremism itself refers to anyone who espouses radical or fanatical positions, religious or otherwise.

In American politics, extremism most often takes on the form of those who advocate for recognition of single issues. The articles in this collection explore extremists of gun rights, animal rights and the environment, as well as groups who fanatically oppose the expansion of the government and a womans right to choose. It also touches upon a growing contingent of extremist actors, white nationalists and far-right movements.

The antigovernment movement has been around nearly as long as the founding of the country, and was first expressed when Thomas Jefferson disagreed with Alexander Hamilton about the fundamental role of the federal government. In modern times, the antigovernment movement has cropped up largely in relation to disputes over land ownership and taxation.

The antigovernment movement shares some overlap with gun rights extremists, who argue that the right to bear arms is one of the primary aspects of American democracy. However, as mass shootings have become a frighteningly regular part of American life, these advocates have begun to feel a new urgency to defend the future of America as a gun-wielding nation.

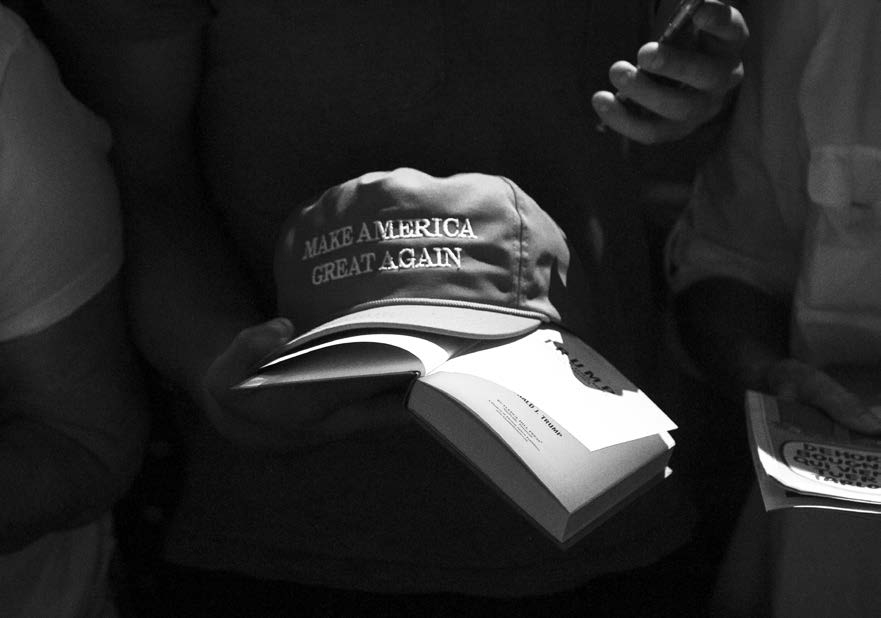

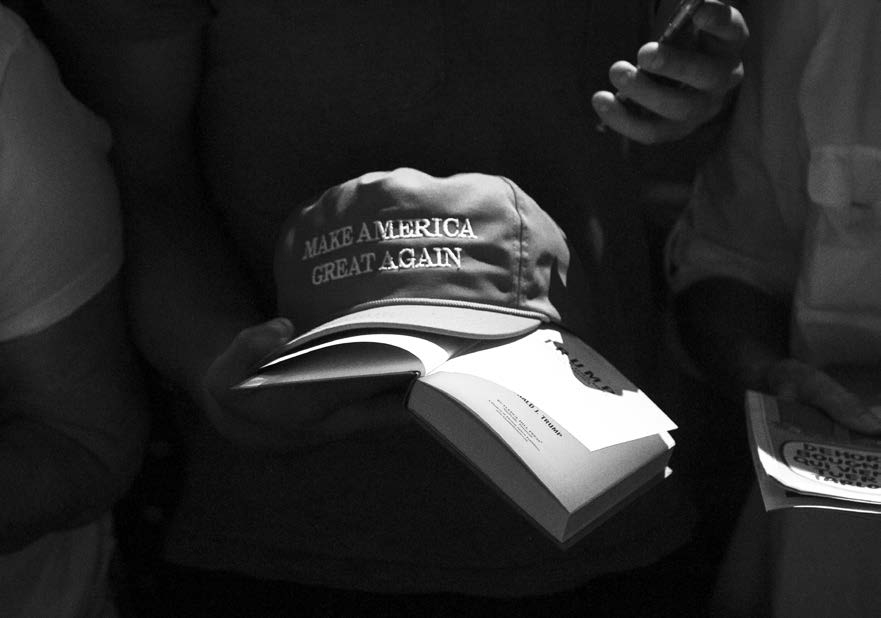

STEPHEN CROWLEY/THE NEW YORK TIMES

A hat with the slogan Make America Great Again during a campaign event for Donald Trump in Raleigh, N.C. Mr. Trump voiced the bewilderment and anger of whites who do not feel at all powerful or privileged.

For the anti-abortion activists who oppose a womans right to choose under any circumstances, the act of terminating a pregnancy amounts to murder. This might explain some of the more extreme actions its supporters have taken in order to prevent abortions from happening in states in the South and the middle of America, ranging from extremely prohibitive legislation to threats of violence some of which have even been carried out. For these radicals, it is a matter of life and death.

White nationalists are an extremist group that has a long history in America, with a prominent presence since the Civil War and Reconstruction. However, since the election of Donald Trump, whose rhetoric echoes some of the talking points used on far-right websites, this group has grown louder and more visible. In August 2017, a rally organized by an alt-right organization was met with protests that quickly turned violent, leading to the death of one counterprotester. This led Americans to wonder where these extremists came from and how they could be stopped.

It is a favorite criticism on both sides of any issue to call those at the opposite end of the political spectrum extremists, whether or not that is based on reality. Some arguments could be made in favor of political extremism: In a two-party system in which policies are watered down by compromise, taking an extremist stance is a way of edging progress forward in a useful direction. But, of course, taking an extremist position often results in a shutting down of discourse and an end to compromise. And ultimately, violence has not been proven to effectively do anything but spread harm.

The 21st century seems to be a century of extremes, fueled in part by the advent of social media and algorithms that filter news in order to feed individual biases and stoke animosity. The rise of extremism can feel frightening, but as the antigovernment extremists demonstrate, these forms of extremism have been part of American culture since the founding of the nation. As time goes on, it will continue to be a fact of our lives.

CHAPTER 1

Antigovernment Extremists

In 2014, a cattle rancher from Nevada named Cliven Bundy led an armed protest against the Bureau of Land Management. This followed nearly two decades of disagreement, with Bundy asserting that the government had no right to regulate public land. Bundy represents a strain of antigovernment extremism that dates back to the countrys founding. The articles in this chapter examine the enduring prevalence of this movement.

Two States, Two Gatherings and a Lot of Antigovernment Sentiment

BY MICHAEL JANOFSKY | MAY 15, 1995

CORNISH, N.H., MAY 13 Some brought family members, some their friends, some just the gun racks in the back of their pickup trucks.

From all over New England, they arrived for a rally of the Patriots movement, about 100 true believers, some of them members of the armed groups that call themselves militias, but nearly all united in the belief that the American political process has broken down, that elected officials no longer respond to the people and that citizens need to defend themselves against Federal agents abusing their power.

The overarching reason were here is that we know the problems were facing, said Barry Buswell, a 36-year-old logger from the far northern New Hampshire town of Pittsburg, about 140 miles away. The only way we can solve them is to stick together. We know a lot more than most Americans.

It seemed an odd and curious event for Cornish, a scenic place populated by millionaires, artists, farmers and factory workers. It is not a town so much as a collection of close-by dots on the map Cornish Center, Cornish Mills, South Cornish midway up the Connecticut River on the states western edge.

Just above Cornish Mills, the longest covered wooden bridge in the nation, built in 1866, connects New Hampshire with Windsor, Vt., and folks along the east bank love to brag that J. D. Salinger lives nearby. They all know where, of course; they just will not tell outsiders.

Next page