Published in 2021 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2021 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2021 The Rosen

Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Cecilia Bohan: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Hanna Washburn: Editor

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Tweet your policy: governance through social media / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: New York Times Educational Publishing, 2021. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642824216 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642824209 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642824223 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Social media Political aspectsJuvenile literature. | Social mediaInfluenceJuvenile literature. | Social mediaJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC K564.C6 T955 2021 | DDC 343.09944dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: The rise of social media has significantly altered the landscape of governance and political participation; Glenn Harvey/The New York Times.

Contents

Introduction

THE 21ST CENTURY has seen a dramatic shift in the landscape of political outreach and participation. The rise of social media offers unprecedented levels of accessibility for those interested in political activism. Platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram provide venues for users to follow others they are interested in and connect with people around the world. All you need is an internet connection to share your opinions and get involved. In this way, social media promises a kind of unprecedented intimacy with political leaders and celebrities. Users can follow them for updates in real time, and offer their own ideas in return. Social media can level the playing field: It provides an online environment where a participatory democracy can take root and flourish.

How effective is this form of digital activism? The New York Times articles collected in this volume paint a picture of a still-evolving system that is complex and far-reaching. At its best, the rapid nature of social media allows activists to share their cause, reach out to their network and quickly grow support. This process is illustrated in the article How the Kony Video Went Viral, where journalists J. David Goodman and Jennifer Preston detail how celebrities with massive Twitter followings shared the link to the Invisible Children video, spreading the cause like wildfire. In just four days, the YouTube video was viewed over 40 million times, raising awareness and support for the victims of Joseph Kony in Uganda. This kind of viral sharing catalyzed the success of other causes online, including the Arab Spring uprisings, Occupy Wall Street movement and the A.L.S. Ice Bucket Challenge.

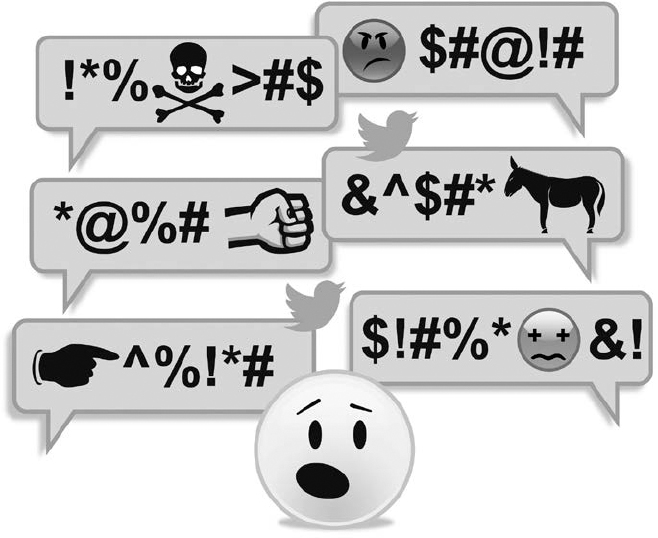

MINH UONG/THE NEW YORK TIMES

As social media becomes a bigger part of the political landscape, many have critiqued this method of participation and activism. Social media encourages us to follow friends and other like-minded users, turning networks into echo chambers, creating insular pockets rather than promoting the sharing of diverse opinions. While Jack Dorsey, Twitters chief executive, told Congress, People do see us as a digital public square, in reality these platforms do not always encourage the open exchange of varied ideas.

Social media has also become an effective venue for terrorist organizations to recruit and spread violence online. Twitter and Facebook especially have been criticized for being slow to restrict this kind of content on their platforms. Social media promises platforms for sharing ideas, but when users begin to spread disinformation and hate, the line between free speech and violence can become blurred. At what point are online platforms responsible for banning users or censoring content?

The 2016 U.S. presidential election marked a significant transition in the use of social media by campaigns and the role of social media platforms as a news source. Donald Trump used Twitter in particular as a tactic to gain a massive following and ultimately win the election. While in office, President Trump has employed Twitter as a tool of governance as well as an opportunity to spark drama and controversy. Journalist Katie Rogers quotes the President saying, in regard to his early tweets, I used to watch it like a rocket ship when I put out a beauty. Trumps use of Twitter has moved beyond a means of communication and sharing; he has created an online persona he uses to his advantage.

Social media is rapidly growing and changing as it thrives on viral sharing and fast-paced updates. Can these platforms change to more effectively serve the public, or are we better off without them? Now that social media has been so integrated into our personal, cultural and political lives, is it even possible to collectively get off the grid?

CHAPTER 1

A Platform for Participation and Activism

With the rise of social media, political participation has never been more accessible or more divisive. Social media activism has allowed widespread involvement in movements like Occupy Wall Street and Kony 2012. As online activism becomes more prevalent, many have critiqued this method, finding it insular, superficial and ultimately ineffective in creating real change. Can activism on social media really facilitate significant progress?

These Revolutions Are Not All Twitter

OPINION | BY ANDREW K. WOODS | FEB. 1, 2011

THE MIDDLE EASTS latest unrest has revived once again a tired debate about the power of social media.

Recent headlines gush about the arrival of the Facebook Revolution or Twitter Diplomacy. Critics like Evgeny Morozov respond by noting that the influence of new media has been exaggerated by a press enthralled with techno-utopianism. Social media enables fast coordination, critics say, not the narrative or resolve necessary to sustain a movement; flashmobs do not a political organization make.

But to state the obvious that Facebook cannot replace good old-fashioned activism is not to say much about what Facebook actually does in a place like Egypt. What does it do?

Malcolm Gladwell, in his recent critique of cyber-activism, argued that the problem with Facebook and its kin is that social networks are only good at certain small tasks that draw on weak social ties. You can easily get a million people to sign up for a cause but that cause is just as likely to be Save Darfur as it is to be the Foundation for the Protection of Swedish Underwear Models. Social media tools cannot supplant the kind of organizing required by, say, the civil rights movement. Social media tools, Gladwell says, are not a natural enemy of the status quo.

But what if revealing the status quo is enough to change it?

Psychologists have long known about a phenomenon called pluralistic ignorance situations in which people keep their true preferences private because they believe their peers do not or will not share their beliefs. In 1975, the sociologist Hubert OGorman showed that pluralistic ignorance was to blame for the false perception white Southerners had that their peers overwhelmingly supported segregation.

Next page