Published in 2019 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2019 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2019 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor John Giacobello: Editor Greg Tucker: Creative Director Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Cyberbullying : a deadly trend / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2019. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642821055 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642821062 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642821079 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: CyberbullyingJuvenile literature. | CyberbullyingPreventionJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HV6773.15.C92 C93 2019 |

DDC 302.34'302854678dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

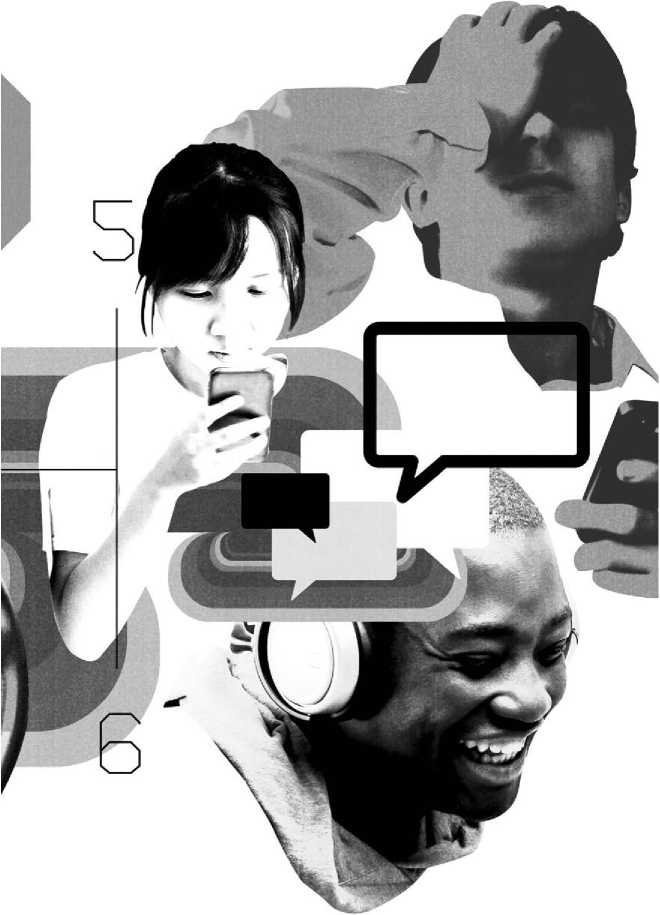

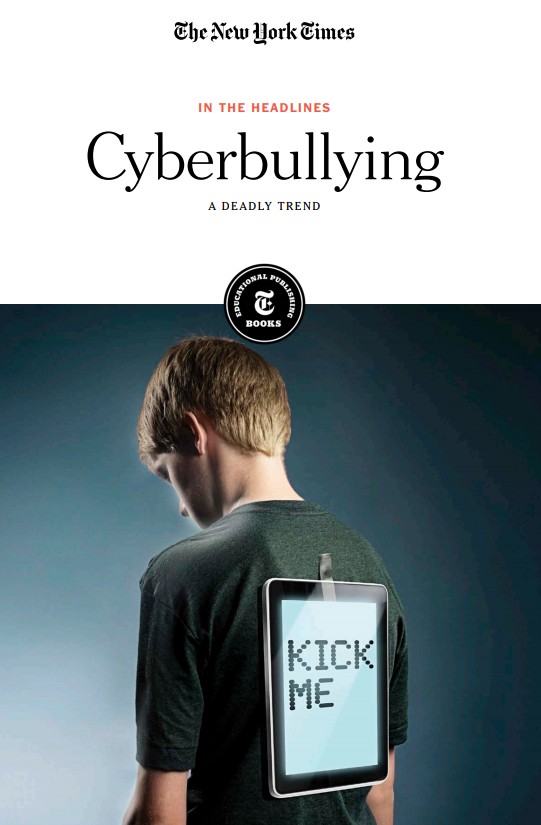

On the cover: Cyberbullying affects people of all ages, and because factors can vary so much from case to case, it's often unclear how individual incidents should be handled; C.J. Burton/ Corbis NX/Getty Images.

CHAPTER 1

The Digital Schoolyard

CHAPTER 2

High-Profile Cases

CHAPTER 3

Technology Evolves

CHAPTER 4

Parenting and Education

CHAPTER 5

Cyberbullying and the Law

Introduction

bullying is not new. Cruelty, abuse and public humiliation have always been unfortunate aspects of human life in some form. But all are rapidly intertwining with technology as it evolves, as social medias grip on culture tightens and as the protective boundaries between private selves and public personae seem to dissolve. Privacy issues that were until recently restricted to celebrities now concern the most anonymous among us. The result has been a kind of Information Age vertigo.

Sadly, young people are the most deeply impacted. Many parents and educators feel helpless in the face of these developments, caught between encouraging children and young adults to immerse themselves in the many benefits of technological innovation, and trying to protect them from the profound damage this same innovation makes possible.

Not long ago a natural human optimism seemed to guide our initial approach to the Internet revolution. Throughout its inception, the miracle of the Information Superhighway was understandably difficult for most to behold with anything short of wonder, while concerns about what may lurk down its darker streets were often dismissed as technophobia. This helped maintain the momentum of countless important developments, from now-commonplace conveniences like online shopping and streaming music, to seismic shifts in politics and social justice. Marginalized groups gained a platform unheard of among past generations of activists.

Meanwhile, cyberbullies and malicious hackers crept from those forgotten dark streets and into the mainstream of our daily lives on the same momentum, leaving us mourning our casualties and scrambling for solutions. Human optimism is tested as we face our most negative habits and tendencies, now enhanced with the use of digital steroids.

STUART BRADFORD

Fortunately many among us are searching for new ways to fight. Monica Lewinsky, possibly the first well-known victim of extreme online harassment, encourages us in a viral campaign to Click With Compassion. Lewinsky maintains that in our online world, clicks are currency, and the less currency provided to negative posts, the less power they can wield. New apps like Brighten, developed by Austin Kevitch, encourage compliments as an alternative to snark. Other apps such as Secret and Yik Yak, widely associated with bullying and gossip, are now defunct due in part to public opposition. High-profile cyber harassment incidents involving celebrities and popular sports teams, however painful for the parties involved, have raised awareness and increased public communication on the issue.

Technology itself is also being creatively deployed to counter online abuse. Instagram, one of the most popular social networks, took a stand against bullying in 2017 with a tool called DeepText. The algorithm tracks down harassing comments in ways more advanced than standard filters used previously. Another new tool called Conversation AI, developed by Google subsidiary Jigsaw, uses artificial intelligence to recognize harassing language and even consider its context.

While these developments are encouraging and important, cyber-bullyings apparent consequences continue, the most tragic and extreme among them being suicide. The link between cyberbullying and suicide can be difficult to prove legally, even in cases where the harasser in literal terms encourages the victim to kill themselves. Why a human being would encourage another to end their life falls beyond the scope of technology and may never adequately be answered. And that mystery may well be the most urgent incentive to bring as much awareness and understanding to the issue as humanly possible.

CHAPTER 1

The Digital Schoolyard

Just as technology has drastically changed the face of education, it has just as powerfully changed the way students relate to one another. This chapter looks at the ways that online communication can make abuse and cruelty easier for young people to inflict on their peers.

More Teens

Victimized by Cyber-Bullies

BY TARA PARKER-POPE | NOV. 27, 2007

the schoolyard bully has gone digital.

As more and more young people have access to computers and cell phones, a new risk to teens is beginning to emerge. Electronic aggression, in the form of threatening text messages and the spread of online rumors on social networking sites, is a growing concern. Researchers estimate that between 9 percent and 34 percent of youth are victims of so-called cyber-bullies. And as many as one out of five teens has bullied another youth using digital media, reports a special issue of the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Although the majority of kids who are harassed online arent physically bothered in person, the cyber-bully still takes a heavy emotional toll on his or her victims. Kids who are tormented online are more likely to get a detention or be suspended, skip school and experience emotional distress, the medical journal reports. Teens who receive rude or nasty comments via text messages are six times more likely to say they feel unsafe at school.

The concern is that bullying is still perceived by many educators and parents as a problem that involves physical contact. Most research and enforcement efforts focus on bullying in school classrooms, locker rooms, hallways and bathrooms. But given that 80 percent of adolescents use cell phones or computers, social interactions have increasingly moved from personal contact at school to virtual contact in the chat room, write Kirk R. Williams and Nancy G. Guerra, researchers at the University of California, Riverside and co-authors of one of the journal reports. Internet bullying has emerged as a new and growing form of social cruelty.

.jpg)

.jpg)