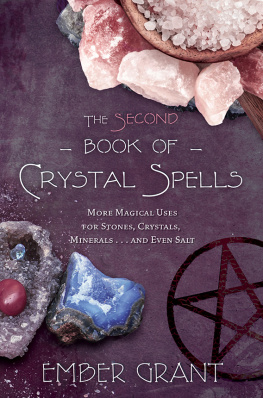

This book would not have been possible without the generous help of those who allowed me to access their beautiful collections. Special thanks to Connie Olson and Leo McFee at Points of Light in Asheville, North Carolinayour crystal shop is one of the most beautiful places Ive had the pleasure of working in. And thank you to Rose Woodfinch, also at Points of Light, for reconnecting me with gem magic. Thank you to Dwaine Ferguson and Heather Kita at Goldsmith Silversmith in Omaha, NebraskaI am so grateful for the time you took to help me select specimens to photograph, and thank you for making me feel a part of your world. Thank you to Denny Lawing of Riviera Fine Minerals in Charlotte, North Carolina. Your passion for rocks and minerals was contagious, and I am grateful for the opportunity to have spent time with you and your collection.

Additional thanks to Leo McFee for reviewing the metaphysical information in this book for accuracy.

Thank you to Christina Spence for helping me get through the first technical edit on the minerals and for always being my scientific sounding board.

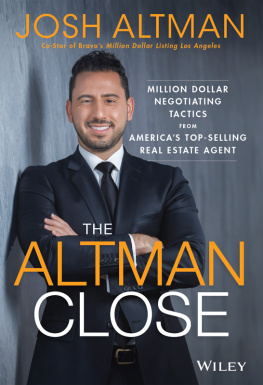

Thank you to Tom Overton for his insightful technical assistance and his generous and beautiful foreword.

Thank you to my dad for buying me my first rock collection after I found that first rock on that hillside when I was eightit cemented a fascination that has never abated.

Thank you to Heather for her gorgeous illustrations and beautiful charts.

Thank you to Bridget, my editor, who believes in my vision and allows me to execute my ideas in the unbelievably supportive environment that is Chronicle Books.

Thank you to Brooke Johnson for her splendid work designing this book.

And thank you to my incredible family who has been so patient and supportive through the writing and shooting process.

uman beings have valued gems and minerals for reasons beyond their mere utility for millennia. Indeed, evidence of humanitys obsession with pretty rocks predates recorded history. Archeologists believe that the oldest examples of natural materials employed for gem usesome of which may date to as many as 100,000 years agowere shells, coral, pearls, amber, and the like. Rocks such as turquoise, jade, and lapis lazuli are also of ancient lineage, having been used in the earliest human civilizations.

uman beings have valued gems and minerals for reasons beyond their mere utility for millennia. Indeed, evidence of humanitys obsession with pretty rocks predates recorded history. Archeologists believe that the oldest examples of natural materials employed for gem usesome of which may date to as many as 100,000 years agowere shells, coral, pearls, amber, and the like. Rocks such as turquoise, jade, and lapis lazuli are also of ancient lineage, having been used in the earliest human civilizations.

Though we may struggle to understand the daily lives of the Neolithic peoples who first collected and worked natural materials for their aesthetic and cultural value, and though such people would be reduced to awestruck wonder at modern society, it is likely that one of the few common points of referenceas basic as food, water, and childrenwould be an appreciation for gem materials. A Neolithic shaman and a modern mineral collector might not be able communicate about much else, but they would share the same reverence for a well-formed quartz crystal.

Gems are mined on almost every continent and in every ecosystem on Earth: from the frozen reaches of Greenland to the torrid deserts of Ethiopia, from the towering heights of the Hindu Kush to the ocean depths off the coast of Namibia, and from the sweltering jungles of Colombia to the arid wastes of the Australian outback. The sole exception is Antarctica, which is protected from mineral exploitation by international treatybut some geologists suspect it could hold rich deposits of diamonds under its vast ice cap. Gems and minerals know no political boundaries. The worlds finest rubies are the product of one of the worlds most despotic regimes in Burma, while some of the richest diamond mines on Earth are found in enlightened, democratic Canada. The mining and marketing of gems and collectable minerals likewise touches the full spectrum of humanity: from the poorest subsistence farmers in Africa and Asia, supplementing their income by digging for gems in the dry season, to the wealthiest individuals on Earth. (One of the gems in Warren Buffetts portfolio is the famed Borsheims, the largest jewelry store in the United States.) A rough pink diamond dug from a riverbed in Africa and sold to a dealer for a few thousand dollars may later sell at auction to a wealthy collector in Geneva for millions.

The cultural importance of gems and minerals is difficult to overstate. Though preferences vary by region and era, one can track the rise and fall of a civilization through its use of gem materials. The Chinese character for jade, (yu), is one of the oldest in the Chinese language (though it accurately refers to a variety of carving stones, including jade), and the procession of Chinese dynasties over the centuries is reflected in the artistic styles of their jade carvings. The ancient Greeks and Romans were fond of engraved gems, and the sophistication of their carvings ebbed and flowed with the heights of their empires. India, the only source of diamonds until the mid-eighteenth century, evolved an elaborate caste system for the stones. Colorless diamonds were assigned to the highest caste and were reserved for royalty. Other colors were assigned to priests, merchants, soldiers, and other occupations, with black diamonds left for common laborers (who probably could not have afforded the gems anyway).

Diamonds bedecked Indian royalty for centuries the maharajahs were renowned for their gem wealth, some of them sporting massive diamond necklaces that would make the flashiest rap artist of the twenty-first century blush. The Mughal emperors of the seventeenth century took things to heights never seen before or since, crafting the legendary Peacock Throne from more than a ton of pure gold and hundreds of rubies, emeralds, diamonds, and pearls. When French gem merchant Jean-Baptiste Tavernier was allowed to inspect the throne in 1665, he estimated its value at 100 million rupees. Its difficult to guess what its value might be today, but on materials alone, it would likely be worth well over $50 million.

Such wealth naturally drew envious gazes. Per-sian emperor Nader Shah sacked Delhi in 1738, carrying away the Peacock Throne and numerous other priceless treasures. When the British conquered the Punjab a century later, in 1849, one of their first acts was to seize the legendary Koh-i-Noor Diamond and spirit it off to London. There it remains as part of the English Crown Jewels, to the continuing irritation of Indian politicians and historians.

The Indians were, of course, not alone in their use of gemstones to mark high status. European monarchs have used gem-encrusted crowns and regalia as symbols of their might since the Dark Ages, and the Egyptian pharaohs spent vast sums filling their tombs with gold and gemstone artifacts. The gold and emeralds of the Incan rulers, much of it believed to have been stolen during the Spanish conquest, have likewise remained the stuff of legend. Wherever archeologists have looked, from Mesoamerica to Celtic Europe to the vast expanses of Asia and Africa, nobility and gems have gone hand in hand.

Naturally, with gems being prized by so many people of power, they have also spawned numerous wars and conquests. The devastation wrought by the Spanish conquistadores in pursuit of emeralds is a matter of bloody historical record. The British conquest of northern Burma in 1885 was driven in part by a desire to control the rich Burmese ruby minesa plan that largely failed, as the Burmese rulers fled with their legendary hoard ahead of the British army. A few years later, diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes (the founder of the De Beers cartel) led his British South Africa Company in the conquest of what would become the nation of Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe), largely in pursuit of diamonds and gold.

uman beings have valued gems and minerals for reasons beyond their mere utility for millennia. Indeed, evidence of humanitys obsession with pretty rocks predates recorded history. Archeologists believe that the oldest examples of natural materials employed for gem usesome of which may date to as many as 100,000 years agowere shells, coral, pearls, amber, and the like. Rocks such as turquoise, jade, and lapis lazuli are also of ancient lineage, having been used in the earliest human civilizations.

uman beings have valued gems and minerals for reasons beyond their mere utility for millennia. Indeed, evidence of humanitys obsession with pretty rocks predates recorded history. Archeologists believe that the oldest examples of natural materials employed for gem usesome of which may date to as many as 100,000 years agowere shells, coral, pearls, amber, and the like. Rocks such as turquoise, jade, and lapis lazuli are also of ancient lineage, having been used in the earliest human civilizations.