The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

FOREWORD

Howell Raines

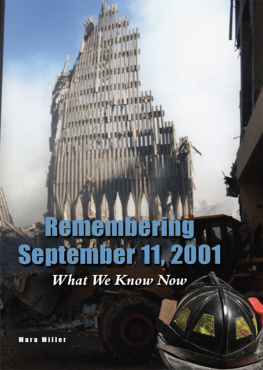

The title of Out of the Blue captures exactly the stark, heartbreaking nature of what happened in the home city of the New York Times on the morning of September 11, 2001. Out of the blue also expresses the suddenness with which the American people were confronted with a new kind of war. Not since Pearl Harbor had United States territory and the American psyche been so abruptly assaulted. It seems to me that every New Yorker, every American, and people around the world will make some personal connections with these four words. I think, for example, of the photograph published on the front page of the Times on September 12 showing the second airplane approaching the south tower of the World Trade Center. The first time the editors saw that photograph, we knew that we were seeing a freeze-frame of a world-altering moment. Richard Bernstein, for his part, opens this book with a meditation upon another stark picturethat of a man, upside down, falling to his death from one of the towers on a glorious fall day. It is an image that sums up the transience of life, the finality of death, the timelessness of the universal sky, and perhaps most of all the fragility of peace.

Some journalism critics and a few readers complained about our decision to print that picture. It was a decision debated in an editors meeting on September 11, and we considered whether friends or loved ones might be able to recognize the falling man. Bernsteins eloquent description of the picture convinces me that its use was the correct journalistic response. Sometimes tragedy must be confronted directly, for it is an indelible part of the human experience. How terrible, for instance, are the pictures of the emaciated survivors of the Nazi death camps, how heartrending Robert Capas photograph of an infantryman being shot in the Spanish Civil War. And how much less would we understand our world if we did not have those images to instruct us about the agony of war and the killing power of hatred in our world.

As daily journalists, of course, we do not set about our work with the idea of being teachers or moral historians. We are engaged in an intellectual enterprise built around bringing quality information to an engaged and demanding readership. Sometimes that means writing what some have called the first rough draft of history. Sometimes it also means constructing a memorial to those whose courage and sacrifice we have recorded orto speak more preciselyerecting a foundation of information upon which our readers can construct their own historical overviews, their own memorials to those who are lost and to the struggle to preserve democratic values.

I offer these observations on journalistic process because as executive editor of the Times, I have a responsibility to the 1,100 men and women of our news department to recognize an extraordinary performance that produced six Pulitzer Prizes, two George Polk Awards, and honors from the Overseas Press Club and the American Society of Newspaper Editors. The work of this generation of Times journalists can stand alongside the best work of our 151 years of newsgatheringin the Civil War, at the dawn of the nuclear age, on the frontiers of space. But you will not find our journalists as actors in the pages that follow, for every writer, photographer, editor, graphic designer, researcher, and support staff member in our newsroom and our bureaus around the world understands that we are not the story. The story of how we got the story has its moments of drama and danger, but even that professional epic is not central to the pages that follow.

What Richard Bernstein, a gifted correspondent, author, and critic, has constructed from his original reporting and the work of his Times colleagues is a record of the things we observed in our roles as witnesses, recorders, and analysts. Bernstein has also drawn on the fine work of our colleagues at other news organizations, and we are proud to credit their contributions. The result is a masterly mosaic that when viewed in its totality gives us a comprehensive picture of the events of September 11, the forces and players that led to them, and the consequences that produced those events. We see the connections between an impressionable young Saudi millionaire and a radical Islamic preacher now serving a life sentence for the first attack on the World Trade Center back in 1993. We see links between a terrorist cell in Hamburg and a flight school in Florida. We glimpse as fully as we ever shall the heroism of passengers on United flight 93, which might have crashed into the White House rather than a field in Pennsylvania.

How fitting that this sweeping international narrative ends quietly with a chapter reminding us of the largest global constituency, those joined by the democratic tombs produced when thunderous events seem to roll out of the blue. In the final chapter, we meet Tsugio Ito, a man who lost a brother at Hiroshima and a son at Ground Zero. The first loss arose from dictatorial passions run amok in his own land, the second by a religious hatred that, one fears, has yet to run its course.

Here, then, is the story up to now, as produced by a news staff whose ability, endurance, and sacrifice awed all of us who were privileged to be part of their enterprise.

AUTHORS NOTE

There is no universally recognized method of transcribing Arabic into English, and that explains why this book, and other books on related topics, contain inconsistencies in their transcriptions of Arabic words and names. Family preferences and historical usages have meant that the same letters in Arabic can come out in two or even three different ways in English. In this book, I have followed the spellings most commonly used in the New York Times. Thus, for example, Marwan al-Shehhi, not Alshehhi, and Nawaf Alhamzi, not al-Hamzi.

ONE

We Saw People Jumping

The forms, sometimes not much more than specks against the gleam of the skyscraper, tumbled downward almost indistinguishable from the chunks of debris, the airplane parts, the vapors of flaming aviation fuel that filled the air like fireworks. They fell at the rate of all falling bodies, thirty-two feet per second squared, slowed a certain amount by the friction of the air, so they fell for eight or nine seconds and they were going at least 125 miles an hour when they hit the pavement or crashed into the roof of the Marriott Hotel at the bottom of the World Trade Center. It took a few instants for the witnesses to understand what they were seeing: that the forms silhouetted against the sky or against the flaming buildings themselves were bodies; they were men and women who had chosen to leap to their deaths from a 110-story building rather than endure the conflagration that had engulfed them inside.

Those eight or nine seconds made up the dreadful interval remaining to these victims, an interval spent hurtling past the vast geometrical precision of windows and pillars downward to death. And then everything, the towers themselves, all 110 ten stories of them, the entire 1,368 feet of the north tower, the 1,362 feet of the south tower with their 400,000 tons of steel and their 10 million square feet of offices, trading spaces, bathrooms, and conference rooms disintegrated in an avalanche of concrete, steel, glass, airplane parts, and thousands more bodies, all compressed into seven stories of rubble below.