WOMAN IN PRISON

* * *

CAROLINE H. WOODS

*

Woman in Prison

First published in 1869

ISBN 978-1-63421-177-2

Duke Classics

2014 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Contents

*

Why Written

*

I was reading an evening paper. I glanced over the advertisements. Oneattracted my attention, and held it so strongly that I read it over andover, again and again. There was nothing unusual in it to ordinaryobservation. It read, "Wanted.At the Penitentiary, a Matron. Inquireat the Institution."

I turned the paper over to read the general news; but could not place mythoughts so as to comprehend the meaning of the words before my sight.Without the intention to do so, I looked again at the advertisement. Itbecame a study to me.

Said ThoughtIf you were to answer that advertisement, and obtain thesituation, it would place you upon missionary ground, and at the sametime give you employment which would afford you a support while you areteaching the ignorant. You would get knowledge in the position. A newphase of life would be opened to your view. You would have anopportunity to observe, practically, how well the present system ofprison discipline is adapted to reform convicts, and repress crime. Butthe cost is too much. I cannot become a Matron in a Penitentiary.

I laid the paper down, without reading it, because I could see nothingin it except that advertisement.

The next day I went in town, sat down in the office of a friend, andtook up a morning paper. No sooner had I opened it than thatadvertisement spread itself out before me. It changed the form of itsappeal; left out what my selfishness might gain, to enlist my compassionand aid, entirely, in what I might accomplish for others. It called tome, in piteous tones, to go work for the prisoner. It was the echo of avoice that I long ago heard, Come into our prisons, and help us, webeseech you!

I cannot! I have other things to do, and they are as much for thebenefit of humanity as anything I may be able to accomplish for you. Myspirit darkened as I made the answer; a cloud of guilt settled down uponit. I threw down the paper in order to dissipate it, and to avoid theplea.

I turned and talked with my friend; but my thoughts were not in what wewere saying. That advertisement followed them, and filled them to theexclusion of every other subject.

In the abstraction which it caused the hour in which I was to leave thecity passed, and I missed my train. I must remain and avail myself ofanother.

While I was waiting, that advertisement returned to my reflections, andurged its cause imperatively as a command. It was a call, to me,resistless as the voice that awoke the young Israelitish Prophet fromhis slumbers. In another moment the struggle with my pride was over, andmy spirit answered,I will go, even to lust-besotted Sodom if thouleadest, Light of my path!

I seated myself in a street car, went to the prison, applied for theplace, and obtained it.

Day by day I wrote down what I saw and heard, what I said and did. Why?In obedience to the same Voice that called me to the work.

The tale is before you.

May it touch the heart of every one who reads the story, and melt itinto a compassion which will labor for the redemption of the prisoner;into a pity which will echo around the cryOpen the prison doors, notto let the prisoner go free, but to let in, to him, the light of moralknowledge, and the discipline of Christian charity.

I - First Day in Prison

*

It was Saturday morning that I became an inmate of the Penitentiary.

I was conducted to the kitchen, where I was to oversee the cooking forthe prisoners, and to the prison adjoining it, which I was to see keptin order, by the Deputy Master of the institution, who gave me my keysand installed me in my office of Prison Matron.

When we first went in he called the six women who do the work in thekitchen, and the three "sweeps" who keep the prison clean, to him, andpresented their new mistress, in my person, to them.

They were convicts that surrounded me at his call; but they were humanbeings. Human faces looked up to mine for sympathy and care. Some ofthem were fine looking, even in their coarse uniform, some were prettyas I picked them out one by one. They all looked at me earnestly, for afew moments, as though they were reading their sentence of harshness orkindly treatment, under my rule, in my face; then, turned away to theirwork again.

They whispered as they stood together, and I saw by their furtiveglances that they were watching, and discussing me, as I walked aroundto take a survey of my new field of labor. They were undoubtedlycommenting upon my personal appearance; and making their predictions asto my sharpness in detecting their impositions, and ability to controltheir perverseness; or, I imagined so.

The Deputy showed me the mush boiler, that would cook two large tubsfull of that farinaceous edible at a time; the potato steamer, thatwould hold four barrels of that esculent vegetable at a cooking; thesoup and coffee kettles, of still larger dimensions; and that comprisedall of the apparatus required in preparing the mammoth meals which wereto serve above four hundred people. These cooking utensils were kept inoperation by pipes conducting steam to them from a boiler stationed inthe middle of the room.

When he put the steam boiler under my direction I shrank back in terrorfrom the task of managing it. The huge culinary apparatus, which he hadbeen exhibiting, although outside the pale of ordinary housekeeping, wasstill within the reach of my understanding; but I had no idea of themanagement of steam; it was not only a difficult, but dangerous affair.

"The house will surely be blown up if you leave the care of that uponme," I said to him.

"You must watch it very closely."

"I don't know how, and I have no aptness for learning that kind ofscience."

"One of the women will tend it." And he went on with explanations thatwere all Greek to me. "It is safe when you have on twenty pounds ofsteam. There is your gauge," and he pointed to a clock-like lookingaffair on the wall. "That hand will move round and tell you how muchsteam you have on. You must keep water enough in the boiler or you willget blown up. If it runs from that centre stopcock, on the side, it issafe. You notice that glass tube in front. The water is just as high inthat as it is in the boiler. This faucet is to let the water off if youget the boiler too full. Turn that faucet when you let the water on,"and he went along and pointed to one in a pipe by the wall, "and thatpump is there in case of accident. You must have it worked every day soas to keep it in order."

All knowledge is useful, I thought, and in time I shall understandrunning a steam-engine. As the women have been trusted with thedangerous thing, they may still continue to be, till I have leisure tolearn the science of steam as applied to cooking.

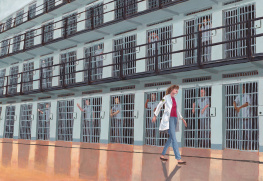

After I had taken a survey of the kitchen the Deputy took me into thewomen's prison which led out of it.

The centre of the hollow square, in which the dormitories are built,looked like a huge block of glittering ice, so white were the washedwalls of brick and stone. The black, grated doors of the cells, insertedinto them, like the teeth of grinning demons, were ranged along thesides about two feet apart, tier after tier, five stories, one aboveanother.