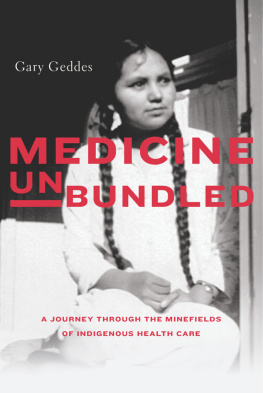

Copyright 2017 Gary Geddes

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, audio recording, or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher or a licence from Access Copyright, Toronto, Canada.

Heritage House Publishing Company Ltd.

heritagehouse.ca

cataloguing information available from library and archives canada

978-1-77203-164-5 (pbk)

978-1-77203-165-2 (epub)

978-1-77203-166-9 (epdf)

Edited by Lara Kordic

Proofread by Lenore Hietkamp

Cover and interior book design by Jacqui Thomas

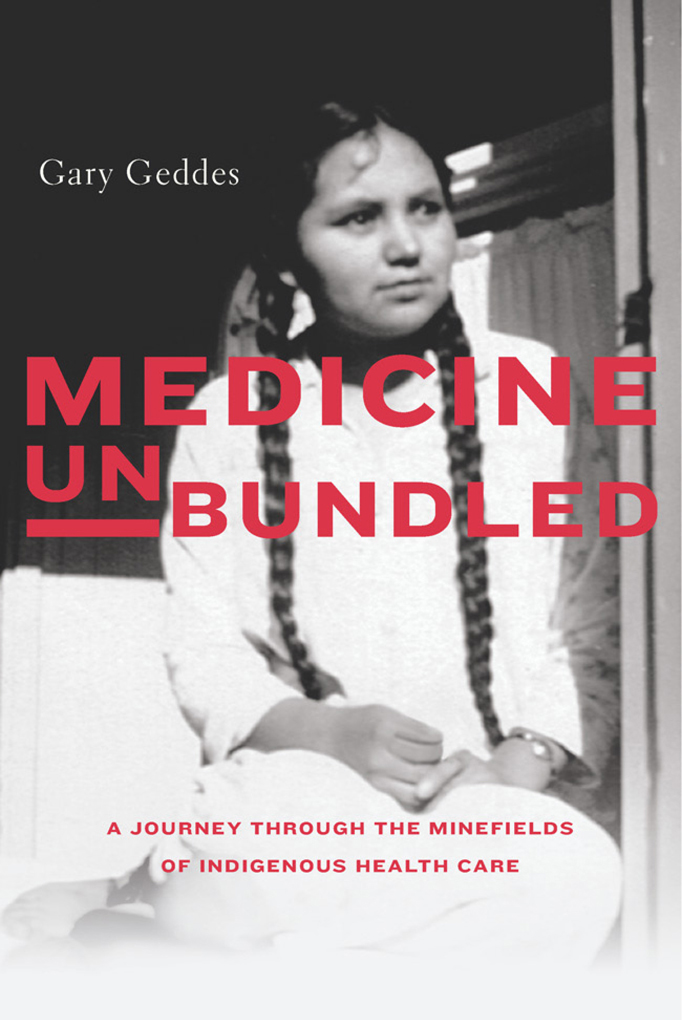

Cover photos courtesy of Joan Morris

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

This book is dedicated to the Indigenous peoples of this land and to those newcomers with open hearts who will come to love them.

If I am given this world with its injustices, it is not so that I might contemplate them coldly, but that I might animate them with my indignation. JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

Table of Contents

.

Acknowledgements

Id like to acknowledge the friendship, generosity, and help provided by so many people over the four years this book has been taking shape. In the case of Joan Morris, this involved numerous enjoyable, troubling, and instructive encounters, during which some of my ignorance of Indigenous history and values was chipped away and a deep friendship and mutual respect developed. Others, like Nancy Gibson, John Whittaker, Clifford Cardinal, Alice Ridout, Ed Sadowski, James Daschuk, Linda McDonald, Marilyn Murray-Allison, Gary Bosgoed, Yvonne Boyer, Kim Recalma-Clutesi, and Adam Dick went out of their way to host, educate, and encourage me. I am grateful to them and others who trusted me enough to share their ideas and experiences, through emails, phone calls, and in person: Eleanor James-Robertson, Roger Ellis, Margaret Nachshen (for the inspiration of and permission to reprint her etching), Lorraine Yuzicapi, Rick Favel, Annie Smith St. Georges, Andr-Robert St. Georges, Saul Day, Theodore Fontaine, Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, Belvie Brebber, Melinda Bullshields, Shirley Horn, Gloria Nicolson, Mike Cachagee, Noel Starblanket, Richard McCutcheon, Chief Robert Joseph, Velvet Maud, Jennifer Mackie, Bill Asikinack, Jonathan Dewar, Amy Bombay, Mary Nicholas, Alex McComber, Albert McLeod, Krista McCracken, Jim Anderson, Stephen Carney, Jody Porter, Albert Dumont, Graham Porter, David Haogak, Mervin Joe, Debbie Gordon Ruben, Catherine Cockney, Gregory Brass, Beverly Amos, Tom OFlanagan, Irene Lindsay, Edward Chamberlain, Dale Burkholder, Margery Fee, Claudia Malacrida, Daniel Josh Rowe, Peter Twohig, Wayne K. Spear, Carol Harrison, Debbie Bookchin, Jim Schumacher, Monique Gray Smith, Miranda Jimmy, Keavy Martin, Lauren McKeon, Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail, George Muldoe, Rayanne Doucet, Karl Hele, Linc Kessler, Carl Urion, and Roy Little Chief. Several people, including Yvonne Boyer, Suzanne Fournier, Nancy Gibson, Rosalyn Boyd, my wife Ann Eriksson, Daniel Coleman, Warren Cariou, Paul DePasquale, and Alice Ridout generously read and commented on the manuscript, saving me from mistakes, misunderstandings, and more than a few graceless moments.

I am especially grateful to the many authors I read, some of whom are quoted extensively in this book. Among them, Suzanne Fournier, James Daschuk, and Maureen Lux deserve a special word of thanks. Suzanne Fourniers Stolen from Our Embrace, which she co-authored with Ernie Crey, was one of the first and most powerful books I read. James Daschuks Clearing the Plains knocked my socks off with its passion and insights into the brutal and nefarious campaign to displace the Indigenous peoples of the prairies. And Maureen Luxs Medicine That Walks informed and inspired me throughout my research and writing. Her brilliant and detailed analysis of the motivations for and the history and legacy of Canadas segregated Indian hospitals, Separate Beds, was unfortunately not released until a week or two before my own research and writing had wound down. For anyone who wants to go deeper into the disturbing story of Indigenous health and wellbeing in Canada, I cannot recommend her new book too highly.

Its a tradition, which Im glad to share, for writers to thank their long-suffering partners. Joseph Conrads wife, Jesse, left his meals outside the door so as not to disturb the genius at his desk. My case is thankfully quite different: no genius, just hard work. My wife Ann Eriksson and I not only shared all the cooking and ate our meals together, but also inspired each other by knuckling down on our respective manuscripts. Her dedication in the research, writing and endless polishing of her fifth novel, The Performance, inspired and sometimes shamed me, for which I am truly grateful.

I want to thank, as well, the staff at Heritage House, including my editor, Lara Kordic, and my publisher, Rodger Touchie, who had faith in this project and offered me a contract after the larger presses in the country had said either This is an important subject, Gary, but wed never be able to sell it, or Sadly, no one in Canada is interested in Indians.

Introduction

What prompts a paleface, and a wrinkled one at that, to write a book about Indigenous health issues in a climate where political correctness reigns and where such folly is likely to be dismissed on all sides as cultural appropriation or worse? I knew the risks of embarking on a project such as this before I began. I was even warned by a few friends and well-meaning specialists that I might end up looking like St. Sebastian, often depicted as a sad and saintly human pincushion shot through with arrows, or like someone whos tried to tango with a porcupine. I made similar questionable forays into sub-Saharan Africa in 2008 and 2009, hoping to learn something about justice and healing, how those suffering from the effects of poverty, genocide, and war managed to reconstruct at least the semblance of a normal life. While in northern Uganda, I interviewed an Acholi woman named Nancy, who had had her ears, nose, and lips cut off by the Lords Resistance Army. As she spoke to me through an interpreter, I couldnt help comparing her story to the situation of Indigenous people back home, where many are living, and dying, in what some have called Fourth World conditions, their bodies dumped in rivers or left frozen outside cities by racist police, neglected children sniffing glue and committing suicide on over-crowded, polluted, postage-stamp reserves, all in one of the most privileged countries in the world.

An abbreviated answer to the question posed above might be this: outrage at what is still happening to Indigenous peoples in Canada, and at my own complicity, set me on this path. More importantly, I was invited to write this book by Joan Morris, an Indigenous acquaintance who, along with members of her family, was grievously mistreated at the Nanaimo Indian Hospital on Vancouver Island. My interviews with Joan led not only to a rich friendship, but also to more in-depth research on a subject about which I had known nothing. Its a long and intriguing story and one that, as the casualties mounted, took me to Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and across Canada several times between 2012 and 2016. But first, let me share a few thoughts about the so-called Indian hospitals and how history gets written.