Table of Contents

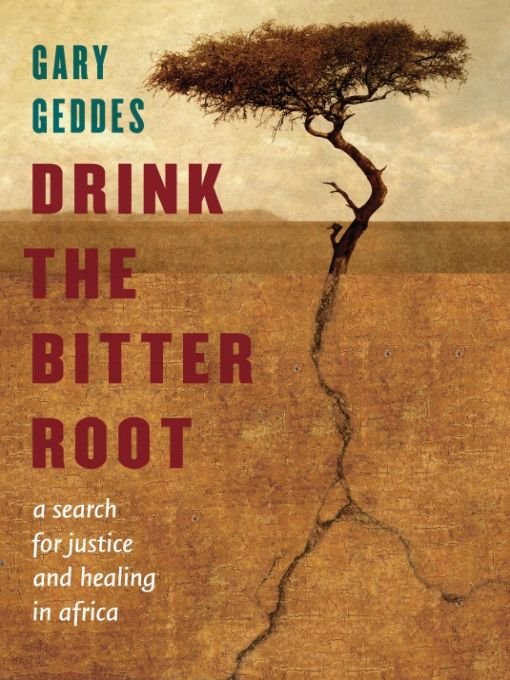

ALSO BY GARY GEDDES

POETRY

War & Other Measures

The Terracotta Army

Girl by the Water

Active Trading:

Selected Poems 19701995

Flying Blind

Skaldance

Falsework

Swimming Ginger

FICTION

The Unsettling of the West

NON-FICTION

Letters from Managua:

Meditations on Politics & Art

Sailing Home:

A Journey through Time, Place & Memory

Kingdom of Ten Thousand Things:

An Impossible Journey from Kabul to Chiapas

Somewhere our belonging particles Believe in us. If we could only find them.

W.S. GRAHAM

Acronyms

| AYINET | African Youth Initiative Network |

| CIDA | Canadian International Development Agency |

| CNDP | National Congress for the Defense of the People |

| CRONGD | Regional Council of Development NGOs |

| CTO | Centre de Transit et Orientation |

| DRC | Democratic of Congo |

| EPRDM | Eritrean Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Movement |

| ICC | International Criminal Court |

| OTP | Office of the Prosecutor |

| ICTR | International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda |

| ICTY | International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia |

| LRA | Lords Resistance Army |

| MONUC | United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic of Congo |

| NATO | North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NRA | National Resistance Army |

| PARECO | Coalition of the Congolese Patriotic Resistance |

| SCF | Save the Children France |

| SHURANET | Somaliland Human Rights Network |

| TASO | The AIDS Support Organization |

| UPDF | Uganda Peoples Defense Force |

| U.N. | United Nations |

| UNICEF | United Nations Childrens Fund |

| UPDF | Uganda Peoples Defense Force |

| USAID | US Agency for International Development |

| WE-ACTX | Womens Equity in Access to Care and Treatment |

one

Taking Aim

IF QUESTION marks hang over a number of my undertakings, the one suspended over this journey was larger than usual. I imagined my wife and daughters looking up at the quizzical symbolI pictured it as a pulsing red neon light in the shape of an inverted umbrella handleand shaking their heads sadly. I shared their quandary. I could hardly breathe in the dust and intense heat, and my vertebrae were rapidly being pulverized from the impact of jagged rocks and potholes. I grabbed my hat and held on as the motorcycle bounced over the treacherous crust of lava and skidded around a corner, sending out a spray of debris into what had once been the main street of Goma, Congos easternmost provincial capital, part of a region where warring militias had contributed to the deaths of four million people and the displacement of even more in the last fifteen years. Several armoured UN vehicles, with troops in full battle gear, roared past us on the left, heading in the opposite direction, away from the front lines. I saw only devastation, a blasted wasteland of ruined buildings. Eruption was the operative word here. Choose your enemy, Goma seemed to say: humankind or nature, its carnage either way. We skirted the remains of a business with gaping windows. A swollen tongue of lava protruded from the doorway, making its implicit comment on the notion of progress.

A kid wearing a blue T-shirt with the word Westmount across the chest shouted as we careened past: Hey, mzungu, watch your ass!

Good advice for a white man, and a warning I would think of often as I travelled through sub-Saharan Africa. It was not so much the statistical enormities that frightened me800,000 butchered in a hundred days, for examplethough these were terrible enough; nor abstractions such as greed, violence and corruption, which can be found anywhere. No, it was the personal stories, some shouted, some delivered in the faintest of whispers, others dragged screaming from the vault of memory. Alice, immobile, her heart turned to stone, describing, sotto voce, the atrocity she was forced to commit; and Nancy, sunlight reflecting off her mutilated face, highlighting the paler scar tissue, talking about forgiveness while I, presumably on her behalf, raged inside and plotted a slow, painful revenge on the perpetrators.

The reason I was in Africa had much to do with a notorious incident in Somalia fifteen years earlier, when a teenager named Shidane Abukar Arone slipped into the military compound where a regiment of soldiers from my country, Canada, were sweating out another African night on the perimeter of Beledweyne, a few hours drive northwest of Mogadishu. Someone had left the gate open. The officers and men of Operation Deliveranceostensibly a peacekeeping mission whose aim was to put a lid on the widespread violence and looting, spinoffs of the civil war still raging in other parts of the countryhad bedded down an hour earlier. At least thats how it must have appeared to the young Somali, his face glistening in the moonlight and his hand, the one clutching prayer beads, unable to stop shaking. He saw bulk food containers, regulation gear, electrical equipment and spare parts for Jeeps and armoured vehicles. How much could he carry, especially if he were forced to run? Would it be food for his family or some item he could sell in the market? Shidane Arone was spared that decision, as his progress was being carefully monitored by one of the sentries on duty. Instead, he would discover the real meaning of deliverance, Canadian-style: hours of brutal torture and mutilation with cigarettes, metal pipes, boots, whatever his captors found readily at hand, his final utterance barely audible through the broken teeth and blood bubbling from his mouth.

The Somalia Affair, as it came to be called, is where my story wants to begin, but it is certainly not the beginning. The magnetic attraction of Africa started in my early teens with the example of medical missionary Albert Schweitzer, whose work amongst the Ogowe people in French Equatorial Africa convinced him that they were more deeply moral than Europeans. The life of Schweitzer, who had a thirst for knowledge and left behind promising careers in Europe as a writer, organist and theologian to study medicine and devote his life to this small community in the colonies, provided the stuff of dreams. Although I later abandoned my faith, or it abandoned me, the missionary zeal to do something of value never quite disappeared. So in 1964, while completing a diploma in education at Reading University in England, I applied for a teaching position at a Roman Catholic high school in Accra, Ghana. I was twenty-four. Shortly after the job was offered to me, reports started to appear in the international press that Ghanas president Kwame Nkrumah, who began his political career as an idealist, a socialist and a pan-Africanist, had turned against the unions and was jailing dissenters, including a number of foreign teachers. I turned down the offer, not realizing at the time that much of what I read was Cold War propaganda and that Belgium, the CIA and various neocolonialist elements were plotting to overthrow Nkrumahs left-leaning regime. But the sense of Africa as unfinished business, or a missed opportunity, remained.