SATISFACTION

Satisfaction

The Science of Finding

True Fulfillment

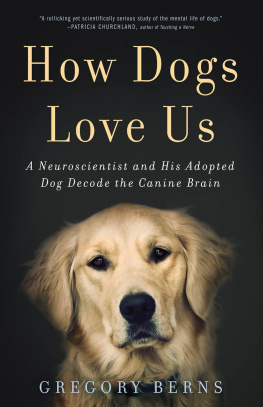

GREGORY BERNS, M.D., Ph.D.

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

Henry Holt and  are registered trademarks

are registered trademarks

of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright 2005 by Gregory Berns

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berns, Gregory.

Satisfaction: The science of finding true fulfillment / Gregory Berns.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-7600-4

ISBN-10: 0-8050-7600-X

1. Satisfaction. I. Title.

BF515. B47205

155.9dc22 2005040259

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2005

Designed by Victoria Hartman

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Kathleen

CONTENTS

PREFACE

What do humans want? Forget about the usual suspects like sex, money, and status. Is there something more basic, a drive that trumps pleasure or pain or happinessthat, if understood, would provide the key to a lifetime of satisfying experiences?

Deep in your brain is a structure that sits at the crossroads of action and reward. Based on a decade of study, I have found that this region, which may hold the key to satisfaction, thrives on challenge and novelty. At first glance, challenge and novelty may seem like things to avoid, but they are the exact ingredients that make for a satisfying experience, and the evidence lies in the one place that matters mostyour brain. Only in the past few years has medical technology in the form of magnetic resonance imagingMRIprovided the hard data that make answers to these questions possible.

First, you must accept that satisfying experiences are difficult to achieve. Just compare how you feel after an hour of watching television, which requires no more effort than choosing which channel to view, with the way you feel after working out for an hour. Or look at hobbies, which may be complicated and challenging but which give great amounts of satisfaction. But these are trivial examples compared with the difficulties of work and life. Ive watched many students come through my lab, and Ive observed how they react to the formidable demands of obtaining a Ph.D. Graduate school, like many pursuits, is a long process without a clearly defined path to the end. Some rise to the challenge, others do not; for those who do, I have seen something deep and lasting emerge from their experience. It is not just satisfaction with a job well done, but the blossoming of a sense of purpose and the stoking of a fire in the belly to conquer more obstacles. The fire, though, is not in the belly. It is in the brain.

Which leads to a second assumption: the essence of a satisfying experience exists within your brain. Knowing where in the brain such a feeling comes from might make satisfication more obtainable, and this knowledge could point the way toward living a life full of satisfying experiences. Not everyone will accept the primacy of the brain in satisfaction, but the feeling I am talking aboutthe sense of accomplishment following the completion of a challenging project or taskis just as real as emotions like happiness or sadness or anger. Ample evidence exists that those emotions arise in the brain. And with new data in hand about the biology of satisfaction, it is time for a serious look at where satisfaction comes from and how to get more of it.

Unlike some other emotions, satisfaction doesnt just fall in your lap. You have to create it for yourself, and doing so requires motivation. Until recently, most researchers assumed that some variation of the pleasure principle governed human motivation. Freud coined the phrase pleasure principle, but the idea that life is composed of the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain goes back at least two thousand years. The pleasure principle is only one of many commonsense ideas about what humans want. But it is wrong. Since the 1990s, neuroscientists were getting closer to cracking the riddle of satisfaction, and, so far, the answer differs significantly from that suggested by the pleasure principle.

Much of what is known about motivation has to do with the neurotransmitter dopamine, which, until the mid-1990s, many scientists thought of as the brains pleasure chemical. While dopamine is released in response to pleasurable activitieslike eating, having sex, taking drugsit is also released in response to unpleasant sensationslike loud noises and electric shocks. Actually, dopamine is released prior to the consummation of both good and bad activities, acting more like a chemical of anticipation than of pleasure. The most parsimonious explanation of dopamines function suggests that it commits your motor systemyour bodyto a particular action. If this idea is correct, then satisfaction comes less from the attainment of a goal and more in what you must do to get there.

How do you get more dopamine flowing in your brain? Novelty. A raft of brain imaging experiments has demonstrated that novel events, because they challenge you to act, are highly effective at releasing dopamine. A novel event can be almost anythingseeing a painting for the first time, learning a new word, having a pleasant, or an unpleasant, experiencebut the key factor is surprise. Your brain is stimulated by surprise because our world is fundamentally unpredictable. Like it or not, nature has given you a brain attuned to the world as it is. You may not always like novelty, but your brain does. You could almost say that your brain has a mind of its own.

Actually, there are many minds in your brain, each with its own set of desires. For instance, there is your mind as you work, your mind when you are at home, and your mind when you are enjoying a fine meal. At any given moment, only one mind is in control of your body, but the simple fact that you can hold competing thoughts in your head at the same time indicates that your other minds constantly vie for control too. When you encounter something novel, dopamine is released, setting off a biochemical cascade in your brain. The process is a little like hitting the reset button on a computer: your other minds, each with their own agenda, might strive to gain the upper hand after the reset. Dopamine is the catalyst for all this action.

Though I do not know how much choice we have in this matter, I have found that seeking out novel experiences keeps dopamine pumping, and I, for one, feel better for it. None of us has many dopamine neurons. From adolescence onward, the amount of dopamine in the brain declines at a steady rate. The evidence is spotty, but a use-it-or-lose-it philosophy probably applies to the brain as much as to the body. But how you use your brain is as important as what you use it for. Perhaps the best way to avoid slipping into the equivalent of a mild case of Parkinsons disease as you age is to keep your dopamine system humming like a well-tuned engine. The most effective way to do so is through novel, challenging experiences. The sense of satisfaction after youve successfully handled unexpected tasks or sought out unfamiliar, physically and emotionally demanding activities is your brains signal that youre doing what nature designed you to do.

Next page

are registered trademarks

are registered trademarks