Skyhorse Publishing

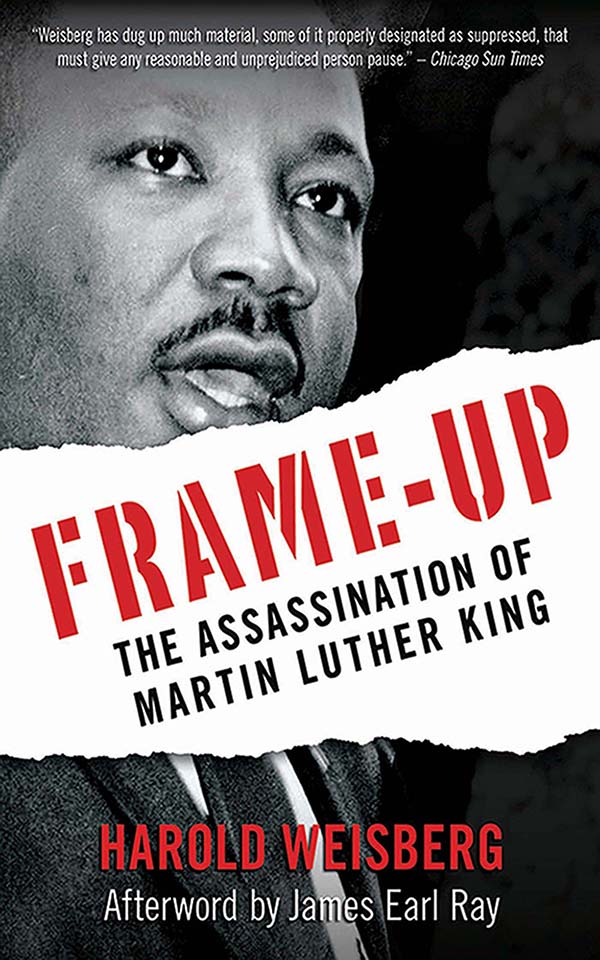

By Harold Weisberg

Whitewash: The Report on the Warren Report

Whitewash II: The FBI-Secret Service Cover-Up

Photographic Whitewash: Suppressed Kennedy Assassination Pictures

Oswald in New Orleans: Case for Conspiracy with the CIA

Post-Mortem: Suppressed Kennedy Autopsy

Post-Mortem III: Secrets of the Kennedy Autopsy

Frame-Up

Copyright 1970, 1993 by Harold Weisberg

Reprinted with permission of Hood College

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-021-1

Printed in the United States of America

Introduction

Since November 22, 1963,1 have devoted myself, with an intensity that has made at least two working days of every one on the calendar, to a close examination and investigation of the political assassinations and what is called the investigation of them. I have published the results of my studies myselfnot for want of trying to interest regular commercial publishers, but because what I had to say was not what, for reasons that varied from publisher to publisher, they wanted to hear or perhaps wanted to have heard.

This book on the case of James Earl Ray and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was begun toward the end of June 1968, the month Robert Kennedy was assassinated. The last few days of that month and the first of July, I continued investigation in New Orleans and adjacent communities. On returning home, I completed the draft of the then-planned book. It contained what I could learn prior to the anticipated trial.

But there was no trial. There was, instead, a deal by which a full and public trial was avoided. On March 10, 1969, there was a minitrial, a dubious proceeding not in any sense a trial, convoked to rubber-stamp that deal. There, instead of evidence, the promise of evidence was substituted, providing only enough for superficial and technical satisfaction of the law as interpreted by those party to that deal.

I then wrote a longer, second book, reporting and assessing this minitrial and the evidence there promised and there suppressed, including involvements and performances of the parties to the deal and many of the questions deliberately avoided.

The book that now appears is based upon the two earlier ones, updated to September 1970. Authors working in current non-fiction deal with developing information. The problem is not new. Nor, when it is in mind during the writing, does it ease the pains of birthing such a book.

The publishers did not tell me what to say or what not to say. They have reduced the long two volumes to a more acceptable size, one that can be of greater use to a larger number of readers, one that can be priced in the popular range. (For scholars and institutions, special arrangements can be made with the author for access to the longer original work.)

In the analysis that follows I shall refer often to the writings of two other men. One is Clay Blair, Jr.s The Strange Case of James Earl Ray, which appeared in March 1969, several days after Rays minitrial in Memphis. In his forward, Blair records that he was aided by the FBI, in itself enough to cast doubt on the book, for the FBI will not even give press releases to those they do not know to support them. In many ways, then, Blairs book is the official story. As to its merits, at this point perhaps it is enough to quote the review by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt in theNew York Times of March 17. The book, he wrote, bears all the earmarks of an instant book to be read by an audience painfully confused....Its literary merits are zero. The review ends: Clay Blairs altogether inconclusive summary of the known record adds practically nothing.

But there is one thing of value in the book, and that Blair does not begin to understand. Tossed in at the end and in no meaningful way included in the content of the book is a transcript of the minitrial. Because in the official typescript it costs about $44.00, it is a considerable saving to be able to buy it for 95 cents. Also, it thus becomes available, now and in the future, to those who might not be able to spend $44.00 for it or who might not know it can be bought from Clerk of the Criminal Court in Memphis, J. A. Blackwell, at 90 cents a page. (The book does not contain the official transcript of the official defense reporting of the proceeding by Martest Otwell, the court reporter. In places it is not consistent with the official stenographic record, but it is faithful to the sense.)

The other writings are those of William Bradford Huie, and we shall have the opportunity to examine in detail both the writings and Huies relations with Ray.

Huie bought Ray.

This is his standard operating procedure. Huie is a tough and tough-minded guy who is and boasts that he is without illusion. He is also a commercial success and commercial-minded, a master of simplified writing in simple, direct sentences comprehensible to those not really comfortable when reading. None of this need be interpreted as adverse criticism. It is not so intended. He is skilled in his craft, this bald, 58-year-old, hard-looking Alabamian, who poses for pictures with a slight smile that sneers a jaundiced view of life and fellow man. He is successful in his calling, and he has earned success. He was established and respected as a writer before turning to the awful racial crimes, the author of six works he calls documentaries and of five novels. Four of the eleven works were made into movies. Success for him means $150,000 a year and living under floodlights, with courage, still in his native (eighth-generation) Alabama, at Hartselle.

In a story by Mel Ziegler in the Miami Heralds Sunday magazine Tropic of November 17, 1968 (because Huie, like almost every other major figure in the case refused to respond when I wrote him, I must depend on secondary sources), the didactic Huieasked about the South, hie responds, thoughtfully, We first have to define the Southsays, quite accurately, There is a great advantage I have over other people in this business. When I go to Mississippi, I carry at least $5,000 in cash. No other reporter is in that position...1 dont have any competition.

Huies first foray into buy-and-sell journalism appeared in the January 24, 1956 issue of Look. James Earl Ray, Huie says, read it in Leavenworth Prison, where he was serving three years for forging postal money orders. He was impressed. After release, he read others of Huies works.

Ray was picked up at Londons Heathrow Airport June 8, 1968. He wrote Birmingham lawyer Arthur Hanes, whom Huie knew (they are on opposite sides of the same business). Huie told Hanes he would buy the literary rights to Ray. Huies $30,000 check to Ray pictured on the