Table of Contents

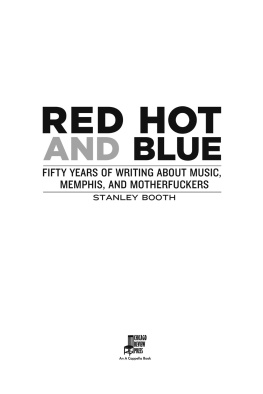

PREVIOUS EDITIONS OF

BEST MUSIC WRITING:

Best Music Writing 2009

GREIL MARCUS, GUEST EDITOR

DAPHNE CARR, SERIES EDITOR

Best Music Writing 2007

ROBERT CHRISTGAU, GUEST EDITOR

DAPHNE CARR, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2005

JT LEROY, GUEST EDITOR

PAUL BRESNICK, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2003

MATT GROENING, GUEST EDITOR

PAUL BRESNICK, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2001

NICK HORNBY, GUEST EDITOR

BEN SCHAFER, SERIES EDITOR

Best Music Writing 2008

NELSON GEORGE, GUEST EDITOR

DAPHNE CARR, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2006

MARY GAITSKILL, GUEST EDITOR

DAPHNE CARR, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2004

MICKEY HART, GUEST EDITOR

PAUL BRESNICK, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2002

JONATHAN LETHEM, GUEST EDITOR

PAUL BRESNICK, SERIES EDITOR

Da Capo Best Music Writing 2000

PETER GURALNICK, GUEST EDITOR

DOUGLAS WOLK, SERIES EDITOR

Introduction

by Ann Powers

Heres a conversation I have at least once a week.

What do you do? says the nice acquaintancea mom Ive met at a bowling party, maybe, or one of my husbands colleagues at the university where he teaches, encountered in the wine line at some professional to-do.

Im a music writer, I say.

Oh, that must be fun, my interlocutor replies. Blank stare. So... what does that mean?

After we determine that, yes, Ive met Prince, and certainly Ive lost some hearing going to so many concerts, the conversation usually dries up. Beyond mentioning their favorite artists, if they have any, and asking me what Im listening to lately (answer: everything, thats my job), most people just dont have a lot to say about music. On a daily basis, its background for them, even if its also sometimes meant the world.

Dont tell me this is because Im in my forties, past the age of loving music to distraction. Its not only true of the parental set I know from squiring around my six-year-old. Ive had the same discussion with fourteen-year-olds, college kids, even the boho professionals who work in related fields like arts programming or librarianship. These friends respect my labor in the pop trenches and are curious about my world; most would never invoke the clich about writing/music/dancing/ architecture that justifies anti-intellectualism and reinforces an outdated high-low cultural divide. Most admire what I do, in the abstract. They just cant see their own way into my song-soaked, rhythm-crazy view of the world.

Which is funny, because many of them live there, too. I constantly witness people engaging in the same practice that occupies so much of my life, simply without committing their acts to text. Real-life examples: when Rebecca talks to her son Walter about what makes that new Avett Brothers record so much better than the last one, thats thinking hard about music. So are Paulines breakdown of how the drums inspire the martial moves in her capoeira class, Gregs argument, with DVD examples, of what makes a great Bollywood soundtrack, and Kathys morning-after report of the U2 concert at the Rose Bowl.

Not to mention all the arguments: about what Obama should have on his iPod, whether garage rock is different than punk rock, if Cher should be forgiven for introducing Auto-Tune to the world, which Al Green album is the best, why rap is in decline (or is it?). And the personal stuff. Theres a lifetime inside a simple statement like, My kid loves the Ramones! Music writing solidifies these passionate exchanges about the sounds that help us define and express our feelings, feel our bodies, and keep moving through life.

Music itself is a call that demands response. It organizes desire, sorrow, and joy into a form both primalthe ear is the first sense organ to begin working when we are in the womband intensely communal; in every known culture, some form of music has been a constant in everyday life. Making music or listening to it is part of how we grow; sharing music is what helps us create community. You dont have to be a musician, or even a major music geek, to exist within that realm. Musical expertise, the star-fan division of labor so prevalent in the classic rock era is, after all, a relatively new concept. A couple of generations ago, before television, many families would sit around and play music together for entertainment, wrote scientist and musician Daniel J. Levitin in his 2006 bestseller This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of an Obsession. Nowadays there is a great emphasis on technique and skill, and whether a musician is good enough to play for others. Music making has become a somewhat reserved activity in our culture, and the rest of us listen. Until recently, the same was generally true about music writing. The lucky (or foolish, given the pay scale) few published their thoughts, and the rest of us read. Yet most everyone is all ears and in tune, responding to each other by channeling the power of the music we hear, and love or hate.

Broadband-enabled interactivity had already endangered Levitins postulation by the time his book was published, though the vestigial allure of virtuosity remained powerful on American Idol and in competitive shredding games like Rock Band. Its hardly news that Consciousness 2.0 is dissolving the century-old division between amateur and professional in the music sphere. In his recent article The New Parlor Piano: Home Recording and the Return of the Amateur, the historian Karl Hagstrom Miller notes that in 2007 the money spent on musical instruments nearly matched income going to prerecorded music. Acquiring the skills for creative musical expression is more popular than it has been for almost a century, he writes. Making music is in. Becoming famous: wildly overrated.

The same is true of music writing, which rarely brought fame anyway, or even a decent living. These days, music writing is in, maybe more than its ever been. But declaring yourself a music writer (FOR REALS, as the kids in Cali and on the Internet say) is wildly overrated. Theres no money in ita reality of nearly every career choice aside from nursing in these times of economic collapse and restructuring, but particularly true in both journalism and the music industry, two fields hit extra hard by the webs flattening effect on information flow. Theres also precious little authority of the old kind. Expert pronouncements and writerly pirouetting no longer pay any kind of rent.

You know the lament: as bloggers replace critics, and Tweeters replace bloggers, respected media organs shut down, the very sentence structures that once made thought elegant give way to cheap acronyms, and chaos ensues. This environment, the argument goes, is highly threatening to sustained thought. Forget having your life changed by a great music book, the way mine was by Greil Marcuss Mystery Train in 1985. We cant even trust anyone to tell us whether the new Justin Timberlake album deserves five stars.

But I think despair is boring. It lands the worrier in the time-travel trap of longing for the past while fearing the future. It obscures the present. The present is unstable, but thats what makes music writingand all cultural writing, in factso exciting a practice these days. We have to dump our expectations and try to use our voices and our minds in different ways.