ALSO BY WALTER ISAACSON

__________

Einstein: His Life and Universe

A Benjamin Franklin Reader

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

Kissinger: A Biography

The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made

(with Evan Thomas)

Pro and Con

American Sketches

Great Leaders, Creative Thinkers,

and Heroes of a Hurricane

Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2009 by Walter Isaacson

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or

portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address

Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition November 2009

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered

trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at

1-866-506-1949 or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors

to your live event. For more information or to book an event,

contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at

1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Paul Dippolito

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4391-8064-8

ISBN 978-1-4391-8345-8 (ebook)

To Cathy and Betsy, as always

Contents

American

Sketches

INTRODUCTION

My So-called Writing Life

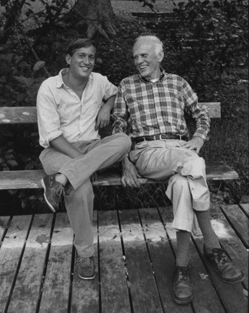

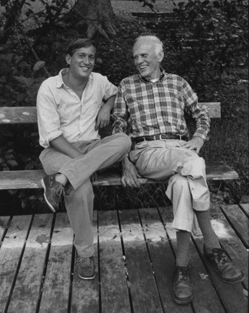

On the Bogue Falaya with Walker Percy,

photographed by Jill Krementz

I was once asked to contribute an essay to the Washington Post for a page called The Writing Life. This caused me some consternation. A little secret of many nonfiction writers like myselfespecially those of us who spring from journalismis that we dont quite think of ourselves as true writers, at least not of the sort who get called to reflect upon the writing life. At the time, my daughter, with all the wisdom and literary certitude that flowed from being a thirteen-year-old aspiring novelist, pointed out that I was not a real writer at all. I was merely, she said, a journalist and biographer.

To that I plead guilty. During one of his Middle East shuttle missions in 1974, Henry Kissinger ruminated, to those on his plane, about such leaders as Anwar Sadat and Golda Meir. As a professor, I tended to think of history as run by impersonal forces, he said. But when you see it in practice, you see the difference personalities make. I have always been one of those who feel that history is shaped as much by people as by impersonal forces. Thats why I liked being a journalist, and thats why I became a biographer. As a result, the pieces in this collection are about peoplehow their minds work, what makes them creative, how they rippled the surface of history.

For many years I worked at Time magazine, whose cofounder, Henry Luce, had a simple injunction: Tell the history of our time through the people who make it. He almost always put a person (rather than a topic or an event) on the cover, a practice I tried to follow when I became editor. I would do so even more religiously if I had it to do over again. When highbrow critics accused Time of practicing personality journalism, Luce replied that Time did not invent the genre, the Bible did. Thats the way we have always conveyed lessons, values, and history: through the tales of people.

In particular, I have been interested in creative people. By creative people I dont mean those who are merely smart. As a journalist, I discovered that there are a lot of smart people in this world. Indeed, they are a dime a dozen, and often they dont amount to much. What makes someone special is imagination or creativity, the ability to make a mental leap and see things differently. In 1905, for example, the most knowledgeable physicists of Europe were trying to explain why a light wave always appeared to travel at the same speed no matter how fast you were moving relative to it. It took a third-class patent clerk in Bern, Switzerland, to make the creative leap, based only on thought experiments he imagined in his head. The speed of light remains constant, he said, but time varies depending on your state of motion. As Albert Einstein later noted, Imagination is more important than knowledge.

The first real writer I ever met was Walker Percy, the Louisiana novelist whose wry philosophical depth and lightly worn grace still awe me when I revisit my well-thumbed copies of The Moviegoer and The Last Gentleman. He lived on the Bogue Falaya, a bayou-like, lazy river across Lake Pontchartrain from my hometown of New Orleans. My friend Thomas was his nephew, and thus he became Uncle Walker to all of us kids who used to go up there to fish, capture sunning turtles, water-ski, and flirt with his daughter Ann. It was not quite clear what Uncle Walker did. He had trained as a doctor, but he never practiced. Instead, he worked at home all day. Ann said he was a writer, but it was not until after his first novel, The Moviegoer, gained recognition that it dawned on me that writing was something you could do for a living, just like being a doctor or a fisherman or an engineer.

He was a kindly gentleman, whose placid face seemed to know despair but whose eyes nevertheless often smiled. I began to spend more time with him, grilling him about what it was like to be a writer and reading the unpublished essays he showed me, while he sipped bourbon and seemed amused by my earnestness. His novels, I eventually noticed, carried philosophical, indeed religious, messages. But when I tried to get him to expound upon them, he would smile and demur. There are, he told me, two types of people who come out of Louisiana: preachers and story-tellers. It was better to be a storyteller.

That, too, became one of my guideposts as a writer. I was never cut out to be a pundit or a preacher. Although I had many opinions, I was never quite sure I agreed with them all. Just as the Bible shows us the power of conveying lessons through people, it also shows the glory of narrativechronological storytellingfor that purpose. After all, its got one of the best ledes ever: In the beginning... The parables and narratives and tales in the Bible always seemed more compelling than the parts that tried to decree a litany of rules.

My parents were very literate in that proudly middlebrow and middle-class manner of the 1950s, which meant that they subscribed to Time and Saturday Review, were members of the Book-of-the-Month Club, read books by Mortimer Adler and John Gunther, and purchased a copy of the Encyclopaedia Britannica as soon as they thought that my brother and I were old enough to benefit from it. The fact that we lived in the heart of New Orleans added an exotic overlay. Then as now, it had a magical mix of quirky souls, many with artistic talents or at least pretensions. As the various tribes of the town rubbed up against each other, it produced sparks and some friction and a lot of joyful exchange, all ingredients for a creative culture. I liked jazz, tried my hand at clarinet, and spent time in the clubs that featured the likes of reedmen George Lewis and Willie Humphrey. After I discovered that one could be a writer for a living, I began frequenting the French Quarter haunts of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams and sitting at a corner table of the Napoleon House on Chartres Street keeping a journal.

Next page