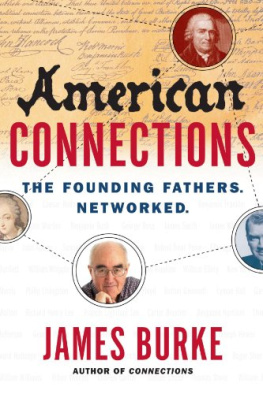

ALSO BY JAMES BURKE

Connections

The Day the Universe Changed

The Axemakers Gift

(with Robert Ornstein)

The Pinball Effect

The Knowledge Web

Twin Tracks

CIRCLES

50 Round Trips through History, Technology, Science, Culture

JAMES BURKE

ILLUSTRATED BY DUAN PETRI I

I

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2000 by London Writers

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

First Simon & Schuster paperback edition 2003

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster special sales:

1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com.

Illustrations by Duan Petrii

Designed by Karolina Harris

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Burke, James, 1936

Circles : 50 round trips through history, technology, science, culture / James Burke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. TechnologyHistory. 2. ScienceHistory. I. Title.

T18.B86 2000

609dc21 00-057335

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-0008-0

ISBN-10: 0-7432-0008-X

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-4976-8 (Pbk)

eISBN-13: 978-1-4391-2795-7

ISBN-10: 0-7432-4976-3 (Pbk)

The essays originally appeared in Scientific American and are reprinted with permission. Copyright 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, and 1999 by Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved.

To Madeline

CONTENTS

CIRCLES

FOREWORD

I SUPPOSE THE real reason for taking an interest in history is, as some ships navigator must have once said, you can only predict where youre going if you know where youve been. So it probably seems perverse that I have chosen to write a series of historical tales that go, as it were, round in circles, since, in some way, each of them ends where it begins. This is because of the view I take of how things happen and, specifically, of how you write about them.

First, the view. Like everything in life, the key to success, happiness, and all those other things people want lies in how good you are at prediction. The more accurately you foresee whats coming, the better youre going to be placed to (a) avoid it or (b) benefit from it. The problem is (as history shows all too painfully) that, as the great Danish physicist Niels Bohr once said, Prediction is extremely difficult, especially about the future. This is because the future is almost never a linear extension of the present. Which all too soon becomes obvious. A few cases in point: Gutenberg thought hed print a few Bibles, and thatd be that; in the 1940s the head of IBM said America would need about half a dozen computers, and the magazine Popular Science predicted they would not weigh more than 1 tons; Alexander Graham Bell believed the telephone would be used only to tell people to expect delivery of a telegram.

Trapped inside the knowledge context of the time, people in the past were no better at second sight than we are. Which is why serendipity plays a key role in the historical sequence and the process of change. This is as true for the present as it was for the past. How many times in your own life did things come about thanks to accident of circumstance? Ill bet happenstance played a part in how you met your partner or chose your career or live where you do or a long list of other character-forming events that now make you different from anybody else. That journey from past to present, full of unexpected encounters and events along the way, has brought you to where you are and who you are at this moment, reading these words.

This is why the past is no foreign, unknown land. The people in the past were trapped in their context, just as we are in ours. Nobody back then knew what was going to come round the corner to change his or her best-laid plans.

What makes the investigation of this process so exciting (and often amusing) is that with the benefit of hindsight we can see why they thought and acted as they did. From our high ground we can also see why things almost never worked out the way they expected because, unlike us, they couldnt see round their corner.

This was why the mid-nineteenth-century coal-gas makers threw away their coal-tar by-product, unaware that within a decade it would be revealed as a valuable cornucopia of products including aspirin, antiseptic chemicals, dyes, timber preservative, and fuel.

In the eighteenth century, Italian scientist Alessandro Volta produced a gas-testing eudiometer. It consisted of a bottle into which led two wires whose ends almost touched. The experimenter filled the bottle with the gas to be investigated. A charge of electricity was then sent down one of the wires and jumped the wire gap, and the gas would explode (or not). After this kind of experiment was discontinued, the eudiometer lay around for more than a hundred years. Then it became the basic element of the spark plug.

The eighteenth-century Jacquard automated silk-weaving system, which used perforated paper as a control mechanism, inspired Herman Hollerith to develop the punch card for data processing during the 1880 U.S. census. The tabulating company he founded to exploit his idea went on to become IBM.

As I hope these essays will show, the other fascinating thing about the way events unfold is the extraordinary variety of the elements involved. In spite of the tendency in schools to segment the past into subject areas (history of chemistry, art, music, transportation, and so on) in which advances and discoveries developed the discipline into its modern form, such an approach to teaching very rarely reflects what actually happened. For instance, a history of communication might lead back from the 1947 Bell Labs development by Shockley of the transistor (electronics). It used germanium, the deposits containing which were first located in the United States by nineteenth-century rock-hound William Maclure (geology), who also funded a commune in New Harmony, Indiana, set up by Robert Owen, a mill-manager from Britain (textiles), who learned his utopian views from William Godwin, founder of the socialist movement (politics), whose daughter Mary wrote Frankenstein (novelist), after she married Percy Bysshe Shelley (poet).

The essays in this book follow the same kind of unexpected path in an effort to recreate a feeling of what it was like to be constrained by the contemporary context. I hope that each time the story rounds a corner the reader will experience a little of what it was like to be the characters themselves, and to be as surprised as they were at the turn of events. Sometimes the turn is a trivial matter, sometimes not. Thats how things happened.

Next page

I

I