The Knowledge Web

From Electronic Agents to Stonehenge

and Backand Other Journeys

Through Knowledge

JAMES BURKE

A Touchstone Book

Published by Simon & Schuster

New York London Toronto Sydney Singapore

ALSO BY JAMES BURKE

Connections

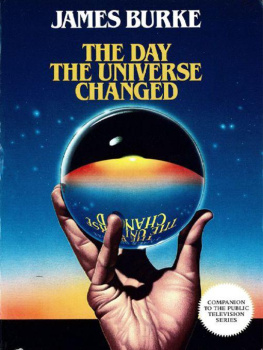

The Day the Universe Changed

The Axemakers Gift (with Robert Ornstein)

The Pinball Effect

TOUCHSTONE

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1999 by London Writers

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

First Touchstone Edition 2000

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Pagesetters

Manufactured in the United States of America

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Simon & Schuster edition as follows:

Burke, James, 1936

The knowledge web : from electronic agents to Stonehenge and backand other journeys through knowledge / James Burke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. TechnologyHistory. I. Title.

T15.B763 1999

609dc21 99-24539

CIP

ISBN 0-684-85934-3

0-684-85935-1 (Pbk)

ISBN: 978-0-684-85935-4

eISBN: 978-1-439-12821-3

www.SimonandSchuster.com

To Madeline

Acknowledgments

I should like to thank Carolyn Doree and Jay Hornsby for their extremely valuable assistance in research.

Contents

Introduction

Change comes so fast these days that the reaction of the average person recalls the depressive who takes some time off work and heads for the beach. A couple of days later his psychiatrist gets a postcard from him. The message on the card reads: Having a wonderful time. Why?

Innovation is so often surprising and unexpected because the process by which new ideas emerge is serendipitous and interactive. Even those directly involved may be unaware of the outcome of their work. How, for instance, could a nineteenth-century perfume-spray manufacturer and the chemist who discovered how to crack gasoline from oil have foreseen that their products would come together to create the carburetor? In the 1880s, without the accidental spillage of some of the recently invented artificial colorant onto a petri-dish culture that revealed to a German researcher named Ehrlich that the dye preferentially killed certain bacilli, would Ehrlich have become the first chemotherapist? If the Romantic movements concept of nature-philosophy had not suggested that nature evolves through the reconciliation of opposing forces, would Oersted have sought to reconcile electricity and magnetism and discovered the electromagnetic force that made possible modern telecommunications?

Small wonder, then, that the man and woman in the street are left behind in all this, if the researchers themselves dont get the point. But given the conditions under which science and technology work, how else could it be? At last count there were more than twenty thousand different disciplines, each of them staffed by researchers straining to replace what they produced yesterday.

These noodling world-changers are spurred on by at least two powerful motivators. The first is that you are more likely to achieve recognition if you make your particular research niche so specialist that theres only room in it for you. So the aim of most scientists is to know more and more about less and less, and to describe what it is they know in terms of such precision as to be virtually incomprehensible to their colleagues, let alone the general public.

The second motivator is the CEO. Corporations survive in a changing world only by encouraging their specialists to generate change before somebody else does. Winning in the marketplace means catching the competition by surprise. Not surprisingly, this process also surprises the consumer, and nowhere so frequently today as in the world of electronics, where by the time the user gets around to reading the manual, the gizmo to which it refers is obsolete.

We live in this permanently off-balance manner because of the way knowledge has been generated and disseminated for the last 120,000 years. In early Neolithic times the requirement to teach the highly precise, sequential skills of stone-tool manufacture demanded a similarly precise, sequential use of sounds and is thought to have given rise to language. The sequential nature of language facilitated description of the world in similarly precise terms, and in due course a process originally developed for chipping pieces off stone became a tool for chipping pieces off the universe. This reduction of reality to its constituent parts is at the root of the view of knowledge known as reductionism, from which science sprang in the seventeenthcentury West. Simply put, scientific knowledge comes as the result of taking things apart to see how they work.

Over millennia, this way of doing things has tended to subdivide knowledge into smaller and more specialist segments. For example, in the past hundred years or so, the ancient discipline of botany has fragmented and diversified to become biology, organic chemistry, histology, embryology, evolutionary biology, physiology, cytology, pathology, bacteriology, urology, ecology, population genetics and zoology

There is no reason to suppose that this process of proliferation and fragmentation will lessen or cease. It is at the heart of what, since Darwins time, has been called progress. If we live today in the best of all possible materialist worlds, it is because of the tremendous strides made by specialist research that have given us everything from more absorbent diapers to linear accelerators. We in the technologically advanced nations are healthier, wealthier, more mobile, better-informed individuals than ever before in history, thanks to myriad specialists and the products of their pencil-chewing efforts.

However, the corollary to a small minority knowing more and more about less and less is a large majority knowing less and less about more and more. In the past this has been a relatively unimportant matter principally because for most of history the illiterate majority (hard-pressed enough just to survive) has been unaware that the problem existed at all. Technology was in such limited supply that there was only enough to share it among a few elite decisionmakers.

It is true that over time, as the technology diversified, knowledge slowly diffused outward into the community via information media such as the alphabet, paper, the printing press and telecommunications. But at the same time these systems also served to increase the overall amount of specialist knowledge. What reached the general public was usually either out-of-date or no longer vital to the interests of the elite. And as specialist knowledge expanded, so did the gulf between those who had information and those who did not.

Each time there was a major advance in the ability to generate, store or disseminate knowledge, it was followed by an information surge and with it a sudden acceleration in the level of innovation that dramatically enhanced the power of the elites. But sooner or later the same technology reached enough people to undermine the status quo. The arrival of paper in thirteenth-century Europe strengthened the hand of church and throne, but at the same time created a merchant class that would ultimately question their authority. The printing press gave Rome the means to enforce obedience and conformity, then Luther used it to wage a propaganda war that ended with the emergence of Protestantism. In the late nineteenth century, when military technology made possible conflicts in which hundreds of thousands died, and manufacturing technology generated untenable working and living conditions for millions of factory workers, radicals and reformers were aided in their efforts by new printing techniques cheap enough to spread their message of protest in newspapers and pamphlets.