THE AXEMAKERS GIFT

Technologys Capture and Control of Our Minds and Culture

JAMES BURKE & ROBERT ORNSTEIN

Illustrations by Ted Dewan

1997

To Madeline and Sally

Acknowledgments

We would first like to thank Carolyn Doree for her many, many megabytes of research work for this book.

We have had the benefit of the work of many others, but especially the research of Alan Parker, John Wood, Jerome Burne (who also read the manuscript), and Lynne Levitan on specific topics.

The book was read and critiqued by a small army of readers, among whom we would like to especially thank Brent Danninger, Evan Neilsen, Howard Gardner, Bob Cialdini, Sally Mallam and Tom Malone. To those couple of dozen who wished to remain anonymous, your advice and suggestions were invaluable.

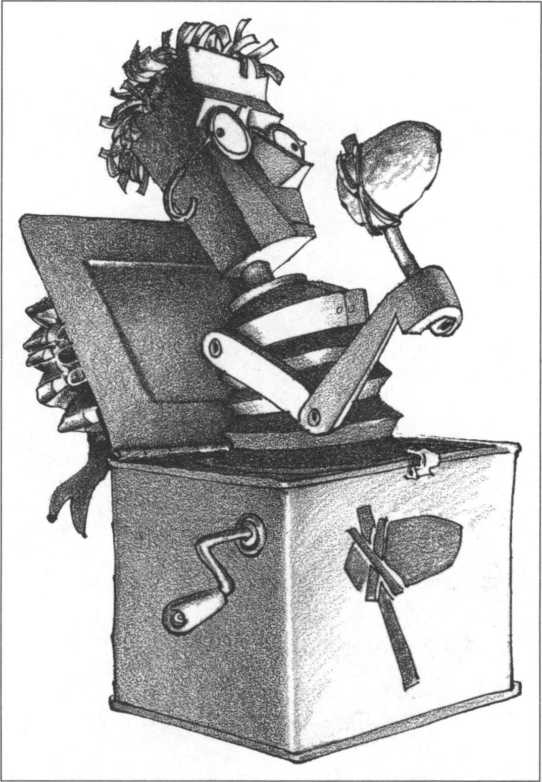

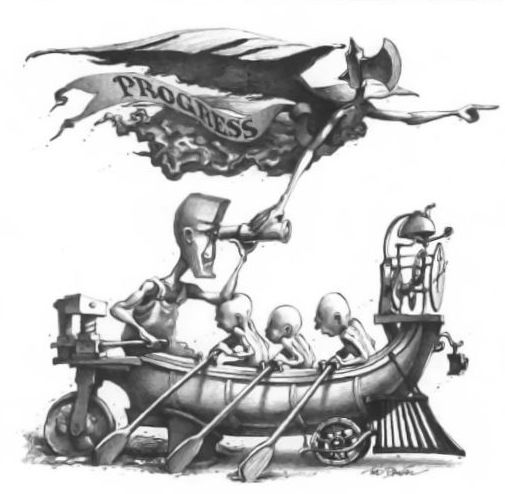

Ted Dewan did a magnificent job of translating our ideas into illustration, and Jane Isay encouraged, coddled, and critiqued the manuscript into a book.

The Guides, the Wardens of our faculties

And Stewards of our labour, watchful men

And skillful in the usury of time,

Sages, who in their prescience would control

All accidents, and to the very road

Which they have fashiond would confine us down

Like engines

William Wordsworth, The Prelude, Book V

PROLOGUE

In his Bostan , Saadi of Shiraz stated an important truth when he told this miniature tale:

A man met another, who was handsome, intelligent, and elegant. He asked him who he was. The other said: I am the Devil.

But you cannot be, said the first man, for the Devil is evil and ugly.

My friend, said Satan, you have been listening to my detractors.

Idries Shah, Reflections

This book is about the people who gave us the world in exchange for our minds. The gifts we accepted from them gave us the power to change the way we lived, but doing so also changed the way we thought. This Faustian bargain was sealed more than a million years ago, but as you will see, the bargain didnt turn out to be quite what either party might have expected.

We call those with whom we made the bargain axemakers. But they make more than axes. They make everything. They make our hopes and dreams. They make what we love and what we hate. They make all this, because they make the tools that change our surroundings. And when their innovations are taken up and used, the effect is to shape the world in which we live, the beliefs for which we fight and die, the values we live by. And our very nature.

Originally the axemakers were ancient hominids who had the talent to reshape stones one piece at a time, and in doing so create tools that would chop up the world. This axemaking ability to do things in the proper order is one of the brains many natural talents. In our ancient past, the all-powerful axemaker talent for performing the precise, sequential process that shaped axes would later give rise to the precise, sequential thought that would eventually generate language and logic and rules, which would formalize and discipline thinking itself. The newly dominant sequential talent of the mind used the cut-and-control-it capability to extract more knowledge from the world and then use that knowledge to cause even further change. Thanks to the axemakers talents and their gifts, at any time things literally would never be the same again.

Look about you and you will find evidence of the axemakers presence in anything you see. The whole of the natural world has been altered by them. The domestication of animals, breeding, horticulture, agriculture, irrigation, architecture, and mining are only a few of the ways in which the axemakers have literally changed the face of the planet.

Axemakers influence practically every aspect of your daily life. Their gifts not only change the world of their time but also remain in use, to affect later periods. Any modern environment is a mixture of these world-altering changes, whose origins range back thousands of years into the past. The fact that you are able to read this book originates with the effects of the fifteenth-century printing press. The food you ate for breakfast today was delivered to the supermarkets thanks to the nineteenth-century combustion engine. The clothes youre wearing now began their existence on a prehistoric loom. You are alive, in all probability, thanks to one or another medical advance dating from some time in the last hundred years.

Your workplace probably includes thirteenth-century paper, sixteenth-century lathe-turned furniture, nineteenth-century plastics, fifteenth-century toilets, seventeenth-century electricity powering nineteenth-century telephones, and early twentieth-century computers. The water supply in the restrooms is delivered by sixteenth-century pumping systems. The paint on the office walls contains nineteenth-century artificial dyes. Your business itself likely runs on a top-down decision hierarchy dating from command structures first established seven thousand years ago to run the first city-states. Your fellow workers probably enjoy male-female relationships influenced by the first ancient stone tools.

By getting into our life, the axemakers get into our heads. Although secondary, the social effects of axemaker innovation also shape those aspects of our lives that cannot be so readily observed. In the fifteenth century, when the astronomer Copernicus rocked the boat with his view of a universe that did not have humankind at its center, he cut the ground from under the established authority of the church. In the late eighteenth century, when the Industrial Revolution suddenly brought hundreds of thousands of farm workers into city factories, their potentially disruptive presence provoked draconian legislation, which included capital punishment for such minor offenses as stealing a handkerchief. In nineteenth-century Western culture, where mechanization was taken to be the sign of an advanced society, those communities unable to adapt easily to technology, or for some other reason remote from it, were regarded as inferior in all aspects of life. Today, television coverage of the glitterati provides influential role models for behavior, while television soap operas offer glimpses of a world whose values many viewers admire and adopt.

Thanks to technological advance, we regard a world of manicured lawns and freshly painted houses as better than the huts, bare earth, and midden heaps among which our medieval ancestors lived. That we may automatically expect our civil rights to be observed springs directly from the fact that such rights are embodied in laws which are disseminated and practiced throughout our society thanks to the invention of print and telecommunications technology. And we tend to dismiss the opinion of old people in part because five hundred years ago Gutenbergs press downgraded their social position, when books began to replace the oral tradition as the main repository of societys experience and accumulated knowledge.

Through history, when the axemakers changed our world in these ways, we were in most cases willing and eager participants in the matter. Most of the time the axemakers gift was irresistible. More often than not it was a cure for a disease, or a faster way to do something, or a means to facilitate what we wanted to do. So we came back for more, unmindful of the other, not easily visible, changes the gift might eventually bring. But we could never unmake history, and with each gift there was no choice but to adapt to the effects of the change.