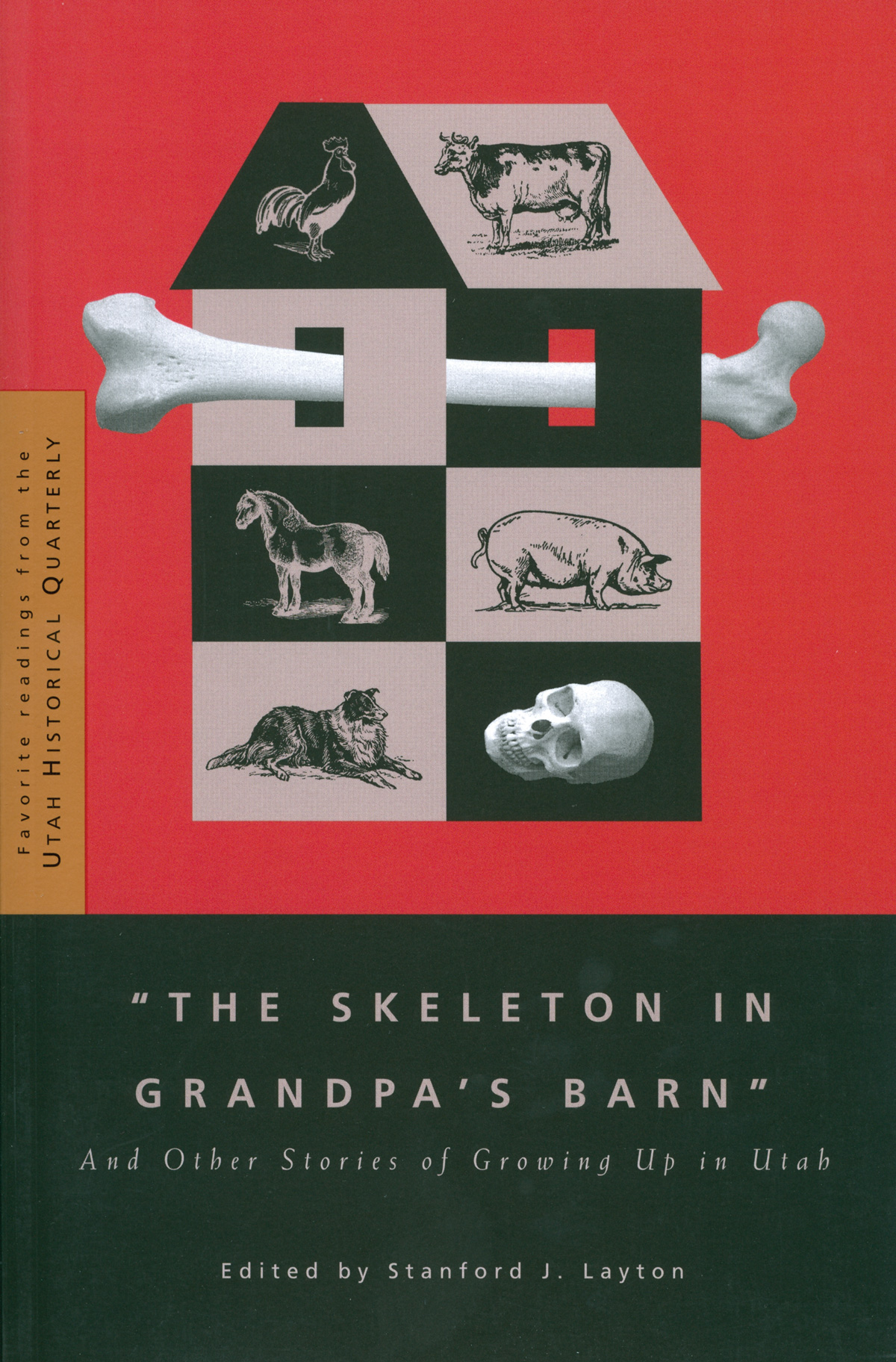

THE SKELETON IN

GRANDPAS BARN

And Other Stories of Growing Up in Utah

Favorite Read ings from the

Utah Historic al Quarterly

Edited by

Stanford J. Layton

Signature Books

Salt Lake City

Cover design by Ron Stucki

2008 Signature Books. All rights reserved.

Signature Books is a registered trademark of

Signature Books Publishing, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The skeleton in Grandpas barn and other

stories of growing up in Utah / edited by Stanford J. Layton.

p. cm. (Favorite readings from the Utah historical quarterly)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56085-160-8

ISBN-10: 1-56085-160-0

1. UtahSocial life and customsAnecdotes.

2. ChildrenUtahSocial life and customsAnecdotes.

3. UtahBiographyAnecdotes.

4. Utah History, LocalAnecdotes.

I. Layton, Stanford J., 1941

II. Utah historical quarterly

F826.6.S58 2008

979.203dc22

2007051429

Contents

Editors Introduction

A fter a hiatus of nearly five years, the Favorite Readings series is back. Thisthe fourth volumeis the largest so far, offering eighteen selections. Each article was previously published in the Utah Historical Quarterly and was chosen on the basis of readability, charm, and its contribution to the historical recordqualities that had made it a personal favorite of the managing editor when it was originally published.

As the subtitle suggests, the unifying theme in this volume is youth. We will see young people make their way across the Utah landscape in a variety of situations and circumstances. In some of the articles, they are typical youngsters engaging in frolic and fun; in some they are innocent victims caught up in tragedy and heartbreak; in others they are simply children dealing with lifes vicissitudescoping, striving, and growing up fast.

The reader will encounter two distinctive types of articles in this volume, intermixed to provide variety. Nine are memoirs and nine are traditional third-person narrative histories. They vary in length from a few pages to full article size. However, in each case they speak to what the social historian Elliott West called the universal experience of young people. Regardless of the age or frame of reference of the individual reader, this book will no doubt stimulate a flood of memories and emotions because we were all young once.

And what youngster never escaped that unforgettable moment of feeling embarrassed by something a parent said or did? The opening article, recalling a crushing moment in the life of a sensitive thirteen-year-old, is of that type. What child cannot recall sneaking into a forbidden place, albeit less spectacular than a niche in grandpas barn that holds a human skeleton? The final article is of that type. The sixteen articles in between deliver the same level of entertainment.

Many, perhaps most, could have happened almost anywhere in the American West, even elsewhere in America. The second selection is a good example. There a child recalls that horrific day in 1924 when the Castle Gate mine explosion killed 176 men, including her father and grandfather. The third article also has a universal complexion as it analyzes the challenges of juvenile rowdyism and delinquency on the Utah frontier.

But as the fourth article illustrates, some of these stories could have happened only in Utah. Here we see the fear and anxieties of children who faced the trauma of federal marshals raiding their homes for polygamous fathers, and we ponder the stresses imposed upon them by having to engage in that occasional act of deceit or to tell that well-rehearsed lie. Later on we step into the shoes of a girl who could not understand why her mother was left alone so often to run the farm while her father was away on church missions.

The states remarkable physical setting also places some of the chapters into a uniquely Utah setting. The haunting story of the gifted Everett Ruess and his mysterious disappearance in the desert is told with perception and insight. From a similar locale, master storyteller Max Robinson vividly recalls the sights, smells, and other sensations of a buggy ride through rural Wayne County in 1924 at age five. The remote nature of Millard County serves to define yet another memoirthat of the wartime experiences of the Uchida family in the Topaz internment camp where children struggled to adjust to wire fences, guard towers, drafty barracks, and poorly equipped schools.

Given the amazing resiliency and optimism of children, it is not surprising that the bulk of these pages ring with the laughter, shouts, and kinetic energy of children being children. They are drawn in wide-eyed wonder to gypsy camps, drop home-made bombs into canyons outside of town, and sled down city streets at exhilarating speeds. One girl describes the familiar faces of people and storefronts as she makes her rounds, donkey-back, through a mining town. Another details the distinctive challenges, torments, hurts, and rewards of straddling cultures in a multiethnic community. We identify with them at every turn. They are us.

Unrepresented in these pages are kings, conquerors, inventors, or other great men and women of history. Rather, this is social history, a genre scholars a few years ago dubbed the New Social History. We read of ordinary people doing ordinary things, with a cumulative effect; the more of these types of articles we read, the keener our understanding of how life really was. In some instances, quantifiable demographic data carry the story; in most, simple anecdotal sources do the job. Each article makes a contribution in its own way.

For those readers who do not particularly care about historiographical classifications but are looking for simple entertainment, joy awaits. What better way to look at Utahs colorful past that through the simple, honest prism of a childs eyes?

1. Never Change a Song

Fae Decker Dix

O ur family lived in a little Utah town called Parowan, the mother colony of southern Utah. Fathers family had been among the first stalwarts to arrive in the beautiful valley of the Little Salt Lake, and on his mothers side they were converters from far back. So father, too, was a converter filled with the missionary spirit and the everlasting zeal to pass it on. He would look at a man a block away and declare he could tell by his walk hes no Mormon. And that settled that man, in my fathers opinion.

He was a huge man, my father, carrying the burden of a huge nameMahonri Moriancumerwhich plagued him much as it became the target of many schoolyard taunts in childhood. He consequently hated nicknames and never allowed us to call each other little pet names in the home. Whatever he named us, that was itat least at home.

But withal he was a kindly man, respectful of women (especially mother), and of his church and country. And while I remember him as stern and towering, he had also a heart as tender as spring grass when it came to counseling us children in our iniquities or caring for us in illness or teaching us to pray in family circle night and morning. We each had our turn.

I remember how his voice rang through the chapel on testimony Sundays as he fervently recalled his missionary experiences in Pennsylvania. They called him the walking Bible back there, and he loved the appellation. For years I thought he alone had converted all of Pennsylvania to Mormonism. He sang in the choir, too, and it was the choir that got us into all that trouble about a favorite Mormon hymn, O Ye Mountains High, Elder Charles W. Penroses stirring contribution to the spirit of a new kingdom.

If only Professor George H. Durham, our respected choir leader, had not gone back to Boston to study at the conservatory. Or if he had not stopped by Salt Lake City on the way home that summer of 1919 and met with the church music committee. Or if only father had not been so set in the first place on keeping alive the spirit of the embattled Mormon pioneer. My sister and I thought of all these things after the episode was over. But it was only an exercise in regret. Professor Durham (our generation always called him that except, maybe, on Sundays when everybody was Brother) did stop by Salt Lake City en route home from his New England studies. And he learned something of great import: Certain of the old Mormon hymns, those of a quarrelsome nature, would be dropped from the next hymn book. Some others would be altered to comply with a new sense of brotherhood, as the time had come to show we lived at peace and not in the persecuted memories of the past.