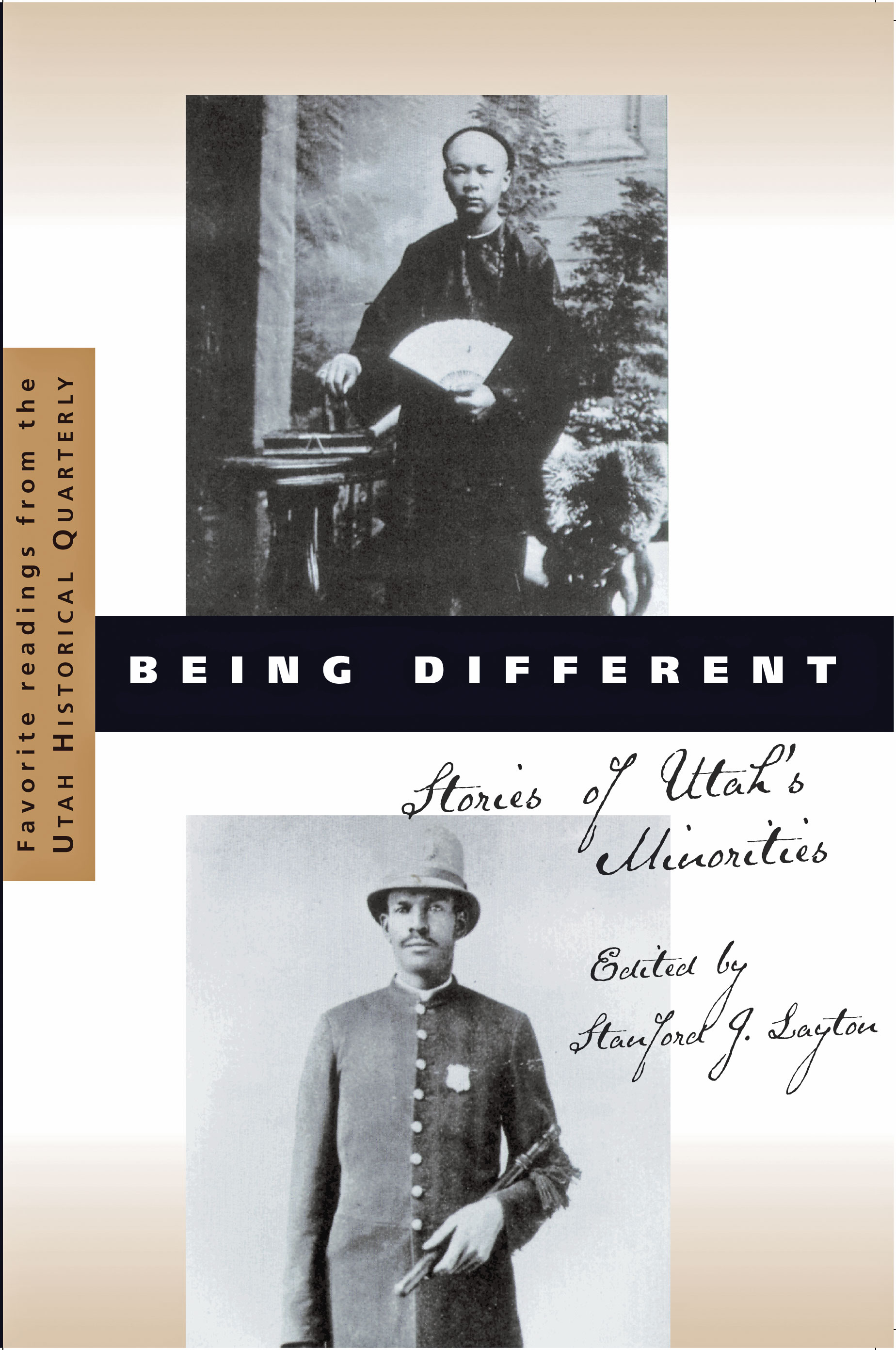

BEING DIFFERENT

Stories of Utahs Minorities

Favorite Read ings from the

Utah Historic al Quarterly

Edited by

Stanford J. Layton

Signature Books

Salt Lake City

Cover design by Ron Stucki

2001 Signature Books. All rights reserved.

Signature Books is a registered trademark of

Signature Books Publishing, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Being different : stories of Utahs minorities / edited by Stanford Layton.

p. cm.

Articles originally published in the

Utah historical quarterly between 1965 and 1995.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56085-150-3 (pbk.)

1. MinoritiesUtahHistoryAnecdotes.

2. MinoritiesUtahSocial conditionsAnecdotes.

3. MinoritiesUtahBiography Anecdotes.

4. UtahEthnic relationsAnecdotes.

5. UtahRace relationsAnecdotes.

6. UtahBiographyAnecdotes. I. Layton, Stanford J.,

II. Utah historical quarterly.

F835.A1 B45 2001

305.8009792dc21

2001049377

Contents

2. The Skull Valley Band of the Goshute Tribe

Deeply Attached to Their Native Homeland

11. The Evolution of Culture and Tradition

in Utahs Mexican-American Community

Editors Introduction

W ell before the New Social History became fashionable in academic circles, Utah Historical Quarterly had a deserved reputation for featuring immigrant peoples, making it a leading journal in this subject area. Numerous articles on ethnic and cultural groups graced the pages of the Quarterly as early as the 1960s. By the 1970s such fare was common. Veteran historians Helen Z. Papanikolas and Richard O. Ulibarri, both members of the Utah Board of State History, and a bevy of younger scholars such as Philip Notarianni, Joseph Stipanovich, and Michael J. Clark were bringing their energies, insights, and leadership to the challenge of discovering and illuminating this rich side of Utahs heritage.

In fact, the Quarterly did not have room to accommodate all the ethnic history suddenly being written in Utah. In 1976 the Utah State Historical Society, with a generous grant from the Utah American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, published a 500-page book, The Peoples of Utah , edited by Helen Papanikolas, containing fourteen chapters on ethnic and cultural groups. Even with that, the surface had barely been scratched. For the next quarter century right to the presentthe Quarterly has continued to benefit from top-notch submissions in this exciting area.

Upon a moments reflection one can easily see why our history reflects such diversity. A prominent feature of our state heritage has been a certain conformity of cultural views, inherent within the religious gathering of the second half of the nineteenth century, but a diversity of national and ethnic backgrounds stemming from that gathering. Scandinavians, Polynesians, Germans, and Britons who converted to Mormonism and relocated to Zion brought with them their distinctive languages, customs, idioms, and traditions. The melt- ing pot functioned somewhat more effectively here than elsewhere, but this image was also still as mythical as real.

Others, including Jews, Chinese, and African Americans, came to Utah in those pioneer times, the latter two joining the Utes, White Mesa Utes, Gosiutes, Paiutes, Northwestern Shoshones, and Navajos as the non-assimilables, to use Richard Ulibarris insightful term. Then as the twentieth century dawned and labor opportunities beckoned, other immigrants came to the Beehive State, and the mix was further enriched. In-migration was nothing new here, but for the first time such nationalities as Greeks, Italians, Yugoslavs (Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), Austrians, Mexicans, and Japanese moved here in significant numbers. With the variety of religions they brought, along with unique customs and generally strong ties to their homelands, these new immigrants were definitely pioneers of a different sort.

The essays that follow embrace most of these ethnic groups, though they are not necessarily intended to be inclusive. Rather, they were selected as personal favorites. Each holds an attractiona definable charmthat has summoned me back again and again through the years. If some of the older articles seem a bit dated in terminology and historiographical context, perhaps the modern reader will overlook this. History is constantly being rewritten as new sources are discovered and new frames of reference take shape. But great story elements are never out of date. The remarkable range of human experience, the aspirations and failures, the unpredictable twists and turns, and, yes, those occasional acts of generosity and nobility that tug at the heartthese are timeless elements of which we never tire. And they are here in abundance, awaiting discovery by those who missed them the first time around or rediscovery by those whose memory of them may have faded.

We begin with Ulibarris survey of ethnic minorities in Utah. Recognized as path-breaking when first published in 1972, it has lost none of its luster through the years. Perceptive and sensitive, it addresses forthrightly the challenges faced by people of color in finding acceptance within a predominately Euro-American culture. Todays readers will find a good deal to ponder here by contemplating how much has changed during the last generation, how much has not, and where our society seems to be heading.

Three essays on Utahs native people follow. Lost amid todays debates regarding nuclear waste repositories in Skull Valley is the simple historical fact that the Skull Valley Gosiutes have held and continue to hold an abiding love of their homelandan area that migrants and overland travelers found hostile and forbidding. This attachment and geographical remoteness, along with the relatively small size of the band, account in large measure for its successful resistance to relocation, first in the nineteenth century and then again in the twentieth. In contrast, the fertile grass-covered ranges of the Northwestern Shoshone in Cache Valley were immediately coveted by white settlers, and love of the homeland was no match for soldiers rifles and the newcomers numbers. Nor was central and southern Utah untouched by Indian-white warfare. Out of the wake of death and destruction caused by the Black Hawk War in the late 1860s came one of the territorys most interesting murder trials. Thomas Jose, defendant, was accused of killing a Paiute named Simeon. The outcomea reflection of many factors, including timing and some cleverly presented forensic evidencereveals a dimension to Indian- white relations that is not commonly seen in the historical record. All three of these situations offer special opportunities for historians, and in each instance a gifted historian has answered the call.

Though most of the new immigrants came to Utah as individuals or single families in search of labor opportunities, some came in organized groups for other reasons. One such was the 24th U.S. Infantry Regiment, transferred to Fort Douglas in 1896. Arriving in the face of hostile editorial opinion from the Salt Lake Tribune and a good bit of uneasiness within the local white community, these buffalo soldiers proved to be remarkably successful ambassadors for the African American community and the military generally. Given the unblushing racial prejudice within white American society of that era, this was a particularly significant historical development for Utah and is still worthy of reflection by thoughtful readers today.

Three other organized movements to Utah were the Polynesian colony at Iosepa, the Jewish colony at Clarion, and the Japanese colony at Keetley. The Polynesians immigrated as Mormons and developed their farming community under LDS church leadership; not surprisingly it was the longest lived and in many ways the most successful such undertaking, lasting from 1889 to 1917. The Clarion Jews, on the other hand, came on their own, though with considerable encouragement from Utah government officials, and laid out their farms in 1910. In retrospect their efforts seem doomed from the start, and their project was abandoned within six years. The Japanese migrated under duress, hurriedly leaving northern California in advance of forced relocation after Pearl Harbor in late 1941. Making the most of a painful and difficult situation, they farmed as best they could in a high mountain valley of Wasatch County and helped to mitigate negative attitudes within the nearby towns. Despair, disappointment, and broken dreams aplenty were in store for each of these groups, but a few triumphs of enterprise and triumphs of spirit were to be theirs as well.