Publication of this book is made possible in part by the proceeds of a permanent endowment created with the assistance of a Challenge Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency.

Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper containing a minimum of 30% post-consumer waste and processed chlorine free.

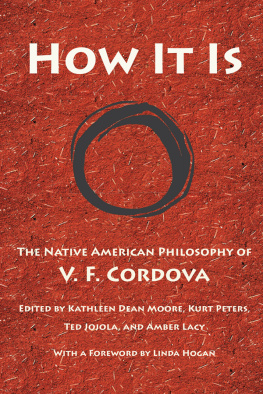

FOREWORD: VIOLA CORDOVA

PERSPECTIVES BY LINDA HOGAN

I am always on my way home.

There is the breathing landscape, the wind.

Ever so rarely a writer comes along and says what others have not found words to say. Usually this writer is a poet and not a philosopher. And yet, philosopher Viola Cordova writes like a poet. As an American Indian woman and thinker, I have long wished for a person who could bring to light and language the significance of indigenous knowledge and the cultural differences of our peoples so eloquently and brilliantly as Viola Cordova, an Apache philosopher. She has gone beyond Euro-Western philosophy into the heart of the indigenous knowledge system and philosophy, as far as the limits of English will allow.

Because our histories, experiences, and ethical thought systems are different from those of Western thinkers she speaks about, the inner architecture of our thought is not easily understood. Cordova does so with an amazing knowledge of the significance of diversity, language, and world knowledge systems. And, because notions of the sacred in Native communities have enough similarities, she is able to speak about these likenesses together in order to further the understanding of indigenous human beings for those who are newer arrivals to this continent.

We dwell in different matrixes in many areas. There is first the relationship with the earth that is the primary experience of tribal peoples whose theology is land-based. Christianity, upon which the Euro-American social structure has come to be based, has what Cordova calls an extraterrestrial god, and traditionally believes in the human elevation out of nature, out of dumb matter. Much is missing in such a belief system, and she notes that it is also a belief system that requires unquestioned foundations of its own mind-set.

I study white people, Viola writes. And she has. As a philosophy major she first learned only one kind of philosophy. It was, for a Native thinker, a closed society that heard only its own voice. Her work here is a lifes work that has tried to add more to these voices.

Missing from those unquestioned regions of belief are stories of our environment, and significant knowledge of the world around us. Our indigenous lives are deeply embedded in nature and place. Our views and understandings of the world are the result of centuries of observing nature and our own place in it. These have remained, in places, for thousands of years. For Native peoples, our systems of knowledge are not about beliefs but about ways of knowing and how we know, through experience itself. It is not what is taught in books, not in ordinary classes, but what lies beneath all the new ideas.

As for the European Americans, she states that they are, a people without a sense of boundaries for themselves, have a lack of attachment to the land, and do not recognize the boundaries of others. They have forgotten the niche they occupy and the stories accompanying that particular bounded place that Cordova calls a homeland. Without a sense of bounded space, there is no sacredness accorded to ones own space of place; one is not standing in the center of the universe looking out onto definite boundaries that define who and what one becomes. There are no sacred mountains, no deep knowledge of the land, the night sky and its own multiple astronomies.

Viola Cordova writes that the stories of all people need to be laid out on the table before one understands how to be fully human. We need to acknowledge the differences and their spectrum of human being, the significance of accepting all and not wishing for a monoculture. Diversity is a way of being, and the attempt to find an absolute is yet another part of the separate matrixes. Tribal peoples do not require a sameness of thought or belief. We come from different stories, different origins, and we respect the differences.

When the fact of human diversity takes second place to the notion of singularity, Cordova writes that this concept of singularity is a dangerous, pernicious concept that ends in misery and hunger. The idea of progress creates sacrificial hostages of the superior beings who make the acme of the end being of that progress.

Part of Cordovas interest in writing and speaking is because others are stealing our voices and telling our stories. Even when they speak with us, even when they interview, what comes out is an interpretation. It is about them, their thoughts.

Usen, which might be considered the word for God for the Jicarilla Apache, means is. According to Viola Cordova, the mystery of understanding tribal concepts of being and goodness seems beyond the comprehension of Europeans who have tried to understand systems that seem to be too complex for them.

The anthropologists and those studying tribal peoples too often write their own interpretation of what is said because they are unable to see larger, to think beyond their own thinking enough to come to what is really spoken, meant, and known about the world. For indigenous peoples, each place has its own intelligence, its own stories. We are not only creatures of this planet but of very specific and fragile circumstances of this planet. We are herd animals. Humans are animals of the group.

The physical space we all share may be the same, but the philosophical space isnt. Native Americans have survived all attempts of eradication and assimilation, for a variety of reasons: the environment is sacred, it is storied, and we are not in a world layered with ideas.

Viola Cordova looks at Native knowledge systems and languages across the country, encompassing a history of continent-wide pain and the effects of European colonization and dominance, and bringing to words how all of our Native systems derive from the heart of place. Even when we have been sent away from that place or have not learned our own languages, we still have it; from subtle gesture and learned ways of being, it is passed down to us. This is How It Is. The knowledge is in the manner of being, even when the words are not spoken. Our philosophies come of being from a place and a community, of knowing a place and respecting its boundaries.

In part, this is why we Native peoples persist in our identities. There is cultural mooring and values having to do with the environment, the place, and the stories of that place. Language is significant also, but even without it, English-speaking Natives see through windows of their old language because of cultural practice. From this she derives her sense of humans in their place in the world, knowing the workings of that place in the world, her notions of bounded space, the territory that is tribal, and the human participation in that space while respecting the boundaries of others.