Published in 2015 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2015 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2015 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to http://www.rosenpublishing.com

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Jeanne Nagle: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Nicole Russo: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Marty Levick: Photo Researcher

Additional material by Kathleen Kuiper

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Native American spirit beings/[edited by] Jeanne Nagle.First Edition.

pages cm.(Gods and goddesses of mythology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62275-400-7 (eBook)

1. Indian mythologyNorth AmericaJuvenile literature.

2. Indians of North AmericaReligionJuvenile literature.

I. Nagle, Jeanne.

E98.R3N38 2015

299.7dc23

2013051224

On the cover: Native American totem poles in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Adina Tovy/Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images

Interior pages graphic iStockphoto.com/Radiocat

CONTENTS

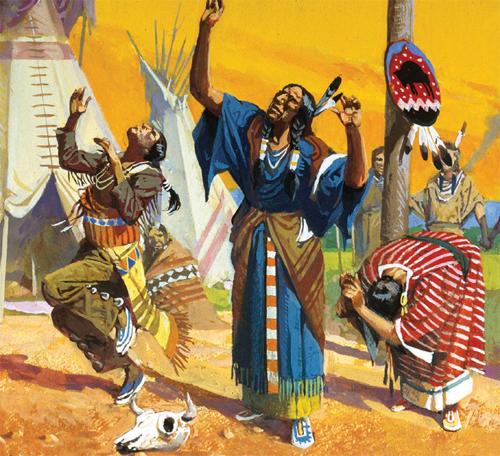

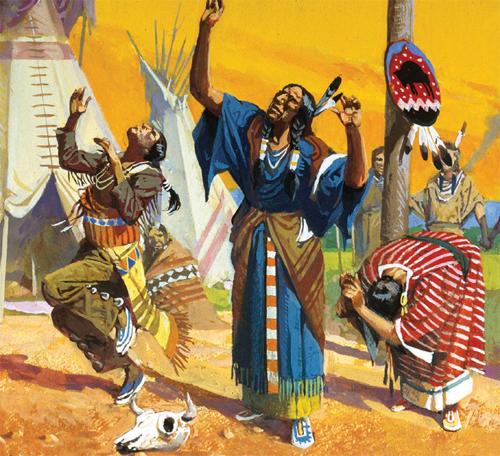

Artist Severino Baraldis interpretation of a Sioux ghost dance. Private Collection/ Look and Learn/The Bridgeman Art Library

U ntil the 1950s it was commonly assumed that the religions of the surviving Native Americans were little more than curious anachronisms, dying remnants of humankinds childhood. These traditions lacked sacred texts and fixed doctrines or moral codes and were embedded in societies without wealth, mostly without writing, and without recognizable systems of politics or justice or any of the usual indicators of civilization. Today the situation has changed dramatically. Scholars of religion, students of the ecological sciences, and individuals committed to expanding and deepening their own religious lives have found in these traditions many distinct and varied religious worlds that have struggled to survive but that retain the ability to inspire.

The histories of these worlds are also marked by loss. Five hundred years of political, economic, and religious domination have taken their toll. Scholars note when complex ceremonies become extinct, but often community members mourn even more the disappearance of small daily rituals and of religious vocabularies and grammars embedded in traditional languagesan erosion of memories that include not only formal sacred narratives but the myriad informal strands that once composed these tightly woven ways of life. Nevertheless, despite the pervasive effects of modern society, from which there is no longer any possibility of geographic, economic, or technological isolation, there are instances of remarkable continuity with the past, as well as remarkably creative adaptation to the present and anticipation of the future.

Native American people themselves often claim that their traditional ways of life do not include religion. They find the term difficult, often impossible, to translate into their own languages. This apparent incongruity arises from differences in cosmology and epistemology. Western tradition distinguishes religious thought and action as that whose ultimate authority is supernaturalwhich is to say, beyond, above, or outside both phenomenal nature and human reason. In most indigenous worldviews there is no such antithesis. Plants and animals, clouds and mountains carry and embody revelation. Even where native tradition conceives of a realm or world apart from the terrestrial one and not normally visible from it, as in the case of the Iroquois Sky World or the several underworlds of Pueblo cosmologies, the boundaries between these worlds are permeable. The ontological distance between land and sky or between land and underworld is short and is traversed in both directions.

Instead of encompassing a duality of sacred and profane, indigenous religious traditions seem to conceive only of sacred and more sacred. Spirit, power, or something akin moves in all things, though not equally. For native communities religion is understood as the relationship between living humans and other persons or things, however they are conceived. These may include departed as well as yet-to-be-born human beings, beings in the so-called natural world of flora and fauna, and visible entities that are not animate by Western standards, such as mountains, springs, lakes, and clouds. This group of entities also includes what scholars of religion might denote as mythic beings, beings that are not normally visible but are understood to inhabit and affect either this world or some other world contiguous to it.

Because religions of this kind are so highly localized, it is impossible to determine exactly how many exist in North America now or may have existed in the past. Distinct languages in North America at the time of the first European contact are often estimated in the vicinity of 300, which linguists have variously grouped into some 30 to 50 families. Consequently, there is great diversity among these traditions. For instance, Iroquois longhouse elders speak frequently about the Creators Original Instructions to human beings, using male gender references and attributing to this divinity not only the planning and organizing of creation but qualities of goodness, wisdom, and perfection that are reminiscent of the Christian deity. By contrast, the Koyukon universe is notably decentralized. Raven, whom Koyukon narratives credit with the creation of human beings, is only one among many powerful entities in the Koyukon world. He exhibits human weaknesses such as lust and pride, is neither all-knowing nor all-good, and teaches more often by counterexample than by his wisdom.

A similarly sharp contrast is found in Navajo and Pueblo ritual. Most traditional Navajo ceremonies are enacted on behalf of individuals in response to specific needs. Most Pueblo ceremonial work is communal, both in participation and in perceived benefit, and is scheduled according to natural cycles. Still, the healing benefits of a Navajo sing naturally spread through the families of all those participating, while the communal benefits of Pueblo ceremonial work naturally redound to individuals.

Next page