P. C. Hodgell

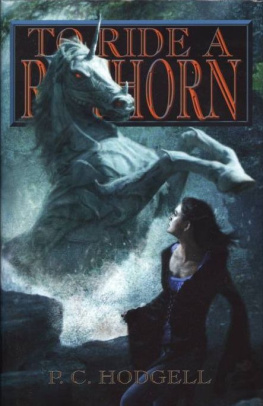

[Kencyrath 04] - To Ride a Rathorn

Chapter I: An Unfortunate Arrival

1st of Summer

I

The sun's descending rim touched the white peaks of the Snowthorns, kindling veins of fire down their shadowy slopes where traces of weirding lingered. Luminous mist, smoking out of high fissures, dimmed the setting sun. A premonitory chill of dusk rolled down toward the valley floor like the swift shadow of an eclipse. Leaves quivered as it passed and then were still. Birds stopped in mid-note. A moment of profound stillness fell over the Riverland, as if the wild valley had drawn in its breath.

Then, from up where the fringed darkness of the ironwoods met the stark heights, there came a long, wailing cry, starting high, sinking to a groan that shook snow from bough and withered the late wild flowers of spring in the upland meadows. Thus the Dark Judge greeted night after the first fair day of summer:

All things end, light, hope, and life. Come to judgment. Come!

On the New Road far below, a post horse clattered to a sudden stop while his rider dropped the reins and stuffed the hood of her forage jacket into her ears. It was said that anyone who heard the bleak cry of the blind Arrin-ken had no choice but to answer it. She had heard but so had the rest of the valley. It probably wasn't a summons to her at all, the cadet named Rue told herself nervously. Surely, she had done nothing that required judgment, even at Restormir, even to Lord Caineron.

Just following orders, sir.

Sweat darkened her mount's flanks and he resentfully mouthed a lathered bit. They had come nearly thirty miles that day from the Scrollsmen's College at Mount Alban, a standard post run between keeps, but not so easy over a broken roadway strewn with fallen trees. They were near home now and the horse knew it, but still he hesitated, head high, ears flickering.

The earth grumbled fretfully and pebbles jittered underfoot. Rue snatched up the reins to keep her mount from bolting. The damn beast ought to know by now that he couldn't outrun an aftershock. Three days ago, a massive weirdingstrom had loosened the sinews of the earth from Kithorn to the Cataracts. The Riverland had been shaken by tremors ever since but, surely, they must end soon.

"Damn River Snake," she muttered, and spat into the water-a Merikit act of propitiation that the Kendar of her distant keep had adopted.

The hill tribes believed that all quakes were caused by vast Chaos Serpents beneath the earth who must occasionally either be fought or fed to be kept quiet. Rue found nothing strange in such an idea but had the sense-usually-not to say as much to her fellow cadets.

Memory made her wriggle in the saddle: "Stick to facts, shortie, not singers' fancies."

That damned, smug Vant. Riverland Kendar thought that they were so superior, that they knew so much.

But only the night before on Summer's Eve, a Merikit princeling had descended, reluctantly, to placate the great snake that lay beneath the bed of the Silver. Rue had seen the pair of feet, neatly sheared off at the ankles, which he had left behind.

The horse jumped again as a silvery form tumbled down the bank and plopped onto the road almost under his nose. With a twist and a great wriggling of whiskers, the catfish righted itself on stubby pectoral fins and continued its river-ward trudge. If the fish were coming back down from the hills, thought Rue, the worst must be over.

She kicked her tired mount into a stiff-legged trot. The sun sank. Dusk pooled in the reeds by the River Silver, then over-flowed them in a rising tide of night. Shadows seemed to muffle the clop of hooves and the jingle of tack.

They crested yet another rise, and there before them lay Tentir, the randon college.

Rue stared. All along the river's curve, the bank had fallen in, taking trees, bridge, and road with it. Parallel to the river, fissures scored the lower end of the training fields, some only yards in length, others a hundred feet or more, all half full of water reflecting the red sky like so many bloody slashes.

Farther back, much of the outer curtain wall had been thrown down. The fields within lay empty and exposed.

The college itself stood well back on the stone toes of the Snowthorns. Old Tentir, the original fortress, looked as solid as ever. It was a massive three-story high block of gray stone, slotted with dark windows above the first floor, roofed with dark blue slate. As if as an afterthought, spindly watch towers poked up from each corner. To the outer view at least, it was arguably the least imaginative structure in the Riverland. Behind it, surrounding a hollow square, was New Tentir, the college proper. While the nine major houses had once dwelt in similar barracks, changes in house size and importance over the centuries had allowed some to seize space from their smaller neighbors. When they could no longer expand outward, they had built upward. The result from this vantage point was an uneven roofline of diverse heights and pitches, rather like a snaggle-toothed jaw. At least none of the "teeth" seemed to be missing, although some roofs showed gaping holes. Rue sighed with relief: she had expected worse.

But what was that, rising from the inner courtyard? Smoke?

Rue's heart clenched. For a moment, she might have been looking down on Kithorn, the bones of its slaughtered garrison lying unclaimed and dishonored in its smoldering ruins. None of her generation had been alive then, eighty years ago, but no one in the vulnerable border keeps ever forgot that terrible story or the cruel lesson it had taught.

To the Riverland Kencyr, however, it was only an old song of events far away and long ago. After all, no hill tribe would dare to try its strength against them.

No. Not smoke. Dust. What in Perimal's name?

The post horse stomped and jerked at the reins, impatient. Why were they standing here? Why indeed? From behind came the click of hooves and a murmur of voices. The main party had almost caught up.

Rue gave her mount its head. It took off at a fast, bone-jarring trot toward stable and home.

II

Inside Old Tentir, shafts of sunset lanced down through the high western windows and through holes in the roof. Dust motes danced in them like flecks of dying fire. The air seemed to quiver. A continuous rumble echoed in the near-empty great hall, punctuated by the crack of a single word shouted over and over, its sense lost in the general, muffled roar.

A Coman cadet stood at the foot of the hall, before one of the western doors beyond which lay the barracks and training ward of New Tentir, the randon college. His attention was fixed on the purposeful commotion outside and his hands gripped the latch, ready to jerk the door open. He didn't hear Rue knock on the front door at the other end of the long hall, then pound.

The unlocked door opened a crack, grating on debris, and Rue warily peered in, one hand on the hilt of the long knife sheathed at her belt. A quick glance told her that the hall was empty, or nearly so. Frowning, she pushed back the hood of her forage jacket from straw-colored hair as rough-cut as a badly thatched roof.

"Tentir, 'ware company!" she shouted down the hall. "Somebody, come take this nag!"

A moment later she had stumbled over the threshold, butted from behind by her horse. She caught him as he tried to shove past, then led him into the hall, needing all her strength to hold him in check. In response, he laid back his ears and arched his tail. Turds plopped, steaming, onto flagstones already littered with broken slates from the roof, downed beams, and fallen birds' nests.