WHAT S IBN HISHM TOLD US

LIBRARY OF ARABIC LITERATURE

EDITORIAL BOARD

GENERAL EDITOR

Philip F. Kennedy, New York University

EXECUTIVE EDITORS

James E. Montgomery, University of Cambridge

Shawkat M. Toorawa, Yale University

EDITORS

Sean Anthony, The Ohio State University

Julia Bray, University of Oxford

Michael Cooperson, University of California, Los Angeles

Joseph E. Lowry, University of Pennsylvania

Maurice Pomerantz, New York University Abu Dhabi

Tahera Qutbuddin, University of Chicago

Devin J. Stewart, Emory University

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Chip Rossetti

DIGITAL PRODUCTION MANAGER

Stuart Brown

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Amanda Yee

FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM COORDINATOR

Amani Al-Zoubi

LETTER FROM THE GENERAL EDITOR

The Library of Arabic Literature series offers Arabic editions and English translations of significant works of Arabic literature, with an emphasis on the seventh to nineteenth centuries. The Library of Arabic Literature thus includes texts from the pre-Islamic era to the cusp of the modern period, and encompasses a wide range of genres, including poetry, poetics, fiction, religion, philosophy, law, science, history, and historiography.

Books in the series are edited and translated by internationally recognized scholars and are published in parallel-text format with Arabic and English on facing pages, and are also made available as English-only paperbacks.

The Library encourages scholars to produce authoritative, though not necessarily critical, Arabic editions, accompanied by modern, lucid English translations. Its ultimate goal is to introduce the rich, largely untapped Arabic literary heritage to both a general audience of readers as well as to scholars and students.

The Library of Arabic Literature is supported by a grant from the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute and is published by NYU Press.

Philip F. Kennedy

General Editor, Library of Arabic Literature

ABOUT THIS PAPERBACK

This paperback edition differs in a few respects from its dual-language hardcover predecessor. Because of the compact trim size the pagination has changed, but paragraph numbering has been retained to facilitate cross-referencing with the hardcover. Material that referred to the Arabic edition has been updated to reflect the English-only format, and other material has been corrected and updated where appropriate. For information about the Arabic edition on which this English translation is based and about how the LAL Arabic text was established, readers are referred to the hardcover.

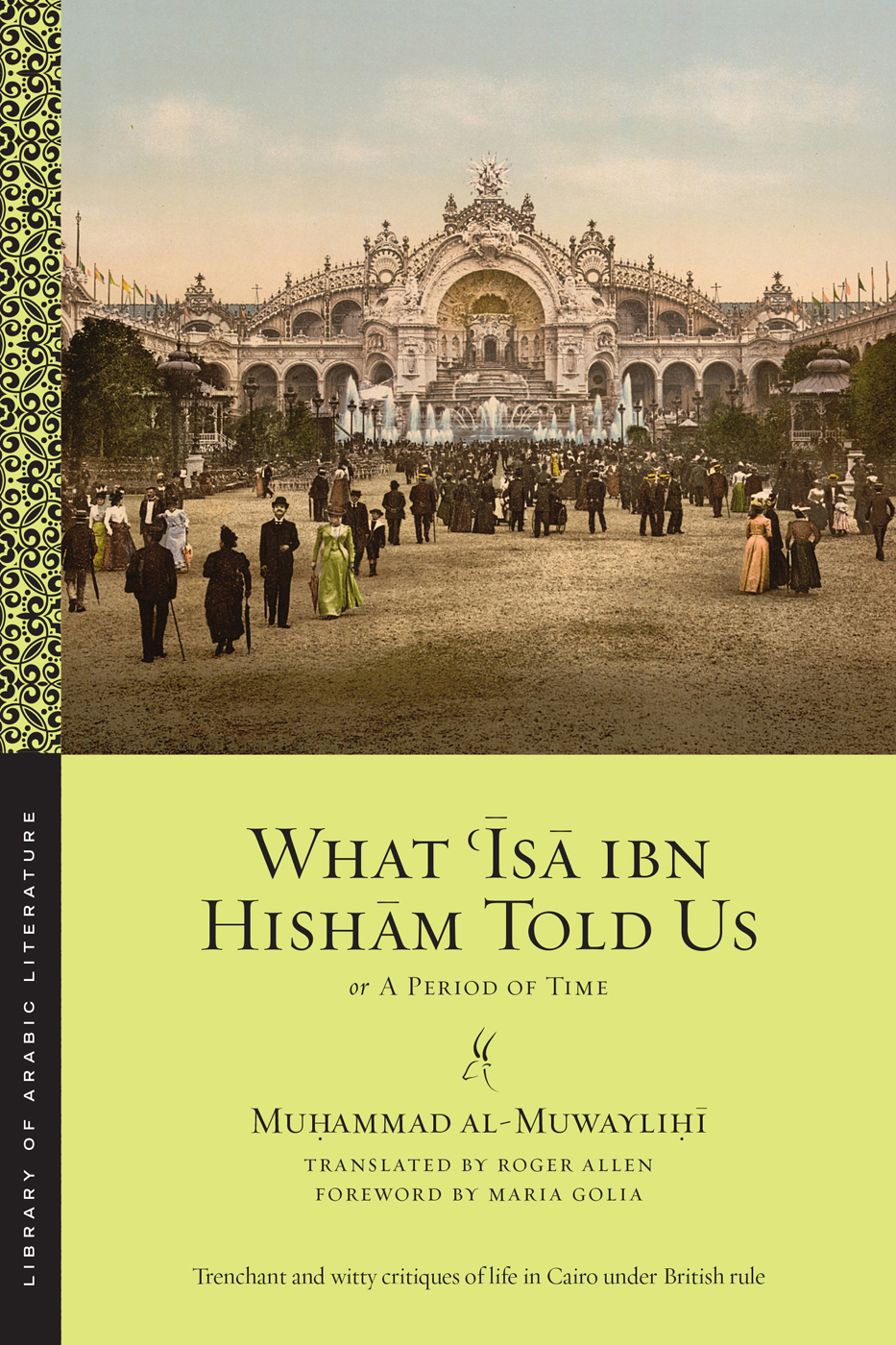

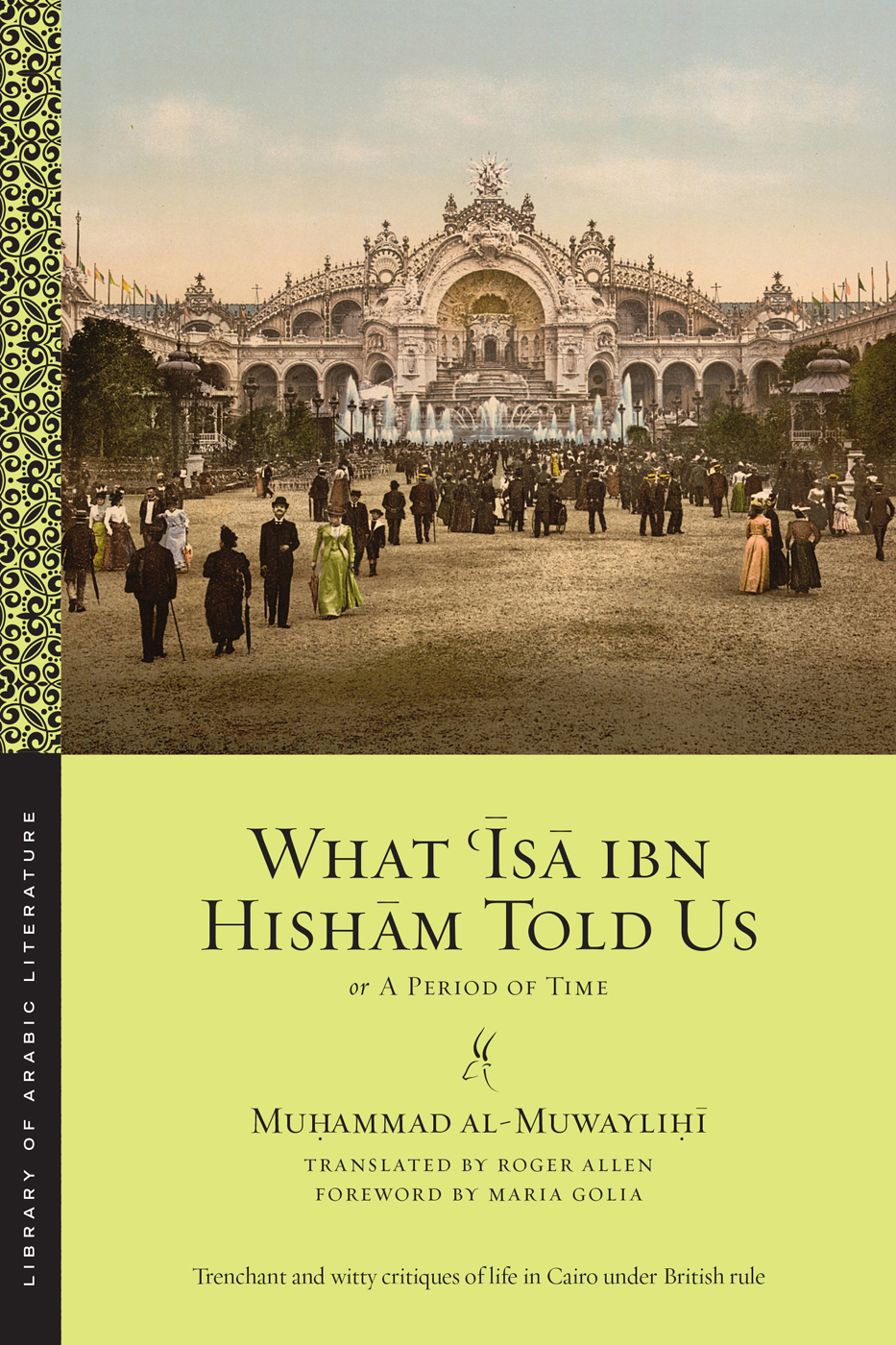

WHAT S IBN HISHM TOLD US

OR

A PERIOD OF TIME

BY

MUAMMAD AL-MUWAYLI

TRANSLATED BY

ROGER ALLEN

FOREWORD BY

MARIA GOLIA

VOLUME EDITOR

PHILIP F. KENNEDY

| NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York |

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

Copyright 2018 by New York University

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Muwayli, Muammad author. | Allen, Roger, 1942 translator. | Kennedy, Philip F. editor. | Muwayli, Muammad. adth Is ibn Hishm. English. | Muwayli, Muammad. adth Is ibn Hishm.

Title: What 'Isa ibn Hisham told us or, A period of time / Muammad al- Muwayli ; translated by Roger Allen ; foreword by Maria Golia ; volume editor, Philip F. Kennedy.

Other titles: Period of time

Description: New York : New York University, 2018. | Series: The library of Arabic literature | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046583 (print) | LCCN 2017045494 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479840915 (paperback) | ISBN 9781479836710 (Ebook) | ISBN 9781479820993 (Ebook)

Classification: LCC PJ7850.U9 H313 2018 (ebook) | LCC PJ7850.U9 (print) | DDC 892.7/35dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046583

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper,

and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability.

Series design and composition by Nicole Hayward

Typeset in Adobe Text

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

MARIA GOLIA

In 1898, when Muammad al-Muwayli and his father Ibrahim began publishing the weekly Mib al-Sharq (Light of the East), the Egyptian press was thriving. Seventy years had passed since the appearance of the Middle-Easts first official gazette, Al-Waqi al-Miriyyah (Egyptian Events, Bulaq Press) announcing affairs of state in Turkish and Arabic. Newspapers had proliferated following the 1882 bombardment of Alexandria and subsequent occupation by the British, many with the intent of fueling nationalist sentiment, others the natural outcome of several decades of break-neck development. The wealth Egypt accumulated by exporting cotton when America was mired in the Civil War, was wisely directed towards infrastructure improvements like railways, the telegraph, telephone, and entire new cities built around the countrys first modern mega-project, the Suez Canal, all of which attracted immigrants from Europe and elsewhere. By the 1890s, newsstands in Cairo and Alexandria overflowed with dailies and periodicals, including cultural, scientific and religious journals in Arabic, Greek, French, Italian, and English, a number of them produced by and for women and circulated throughout the Arab world.

Despite its diversity, readership of the Egyptian press was small, elite and largely foreign; an 1897 census (when Egypts population was about eight million) estimated male literacy at 20 percent in Cairo and Alexandria and in the countryside it was certainly far less. In those pre-radio days however, pubic readings in cafes and at other gatherings made the printed news available to the unlettered. One wonders if Muammad al-Muwayli thought to reach this larger audience as he wrote the articles collected here. By loading traditional story-telling forms (descriptive dialogues, nested narratives and pithy poetic asides) with details of familiar places and personages, he delivered not only the news but a call for awareness of history and for the questioning of authority, ethics and self. However classic the presentation, al-Muwaylis acerbic, insider observations rendered the writing fresh, entertaining and daring.

Shy and perceptive, Muammad al-Muwayli was a natural-born scholar thrust into the world by family and politics. His people were wealthy, his education superb, his father a confidante to royalty, and just fifteen years old when Muammad was born. Ibrahim, who was deeply involved in anti-colonialist political and religious movements, treated his son as a trusted collaborator, at one point making him his emissary to the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul. Beginning in his teens, Muammad partnered with his erudite and outspoken father in publishing endeavors that espoused nationalist agendas and consequently placed them in harms way. At age 22, Muammad was arrested for distributing an anti-British pamphlet his father had authored, taken before a judge, tried and sentenced to death. Thanks to the intervention of a high-ranking family friend he was exiled (temporarily) instead. But being subjected to such harsh and expedient justice is an alarming experience for anyone, however well connected, and it surely colored the scathing accounts of the Egyptian judiciary he later wrote for the

Next page