Originally published in 1948 by Methuen and Co. Ltd. London

Published 2008 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2008 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2008017406

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Darmstaedter, Friedrich, b. 1883.

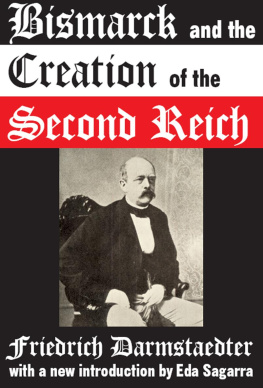

Bismarck and the creation of the Second Reich / Friedrich Darms-taedter.

p. cm.

First published: London: Methuen, 1948.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4128-0783-8 (alk. paper)

1. Bismarck, Otto, Fiirst von, 1815-1898. 2. Political culture--Ger-many--History--19th century. I. Title.

DD218.D27 2008

943.083092--dc22

2008017406

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-0783-8 (pbk)

Friedrich Darmstaedter, whose study of Bismarck appeared just sixty years ago, was not a historian but a lawyer by training and profession. He had been a lecturer in Heidelberg, then as now one of Germanys leading universities, before going into exile from Hitlers Third Reich. His short monograph covered Bismarcks early years and career up to a defining moment in German history: 1871. As in the case of Erich Eyck before him, the author of the three-volume critical Bismarck. Life and Work (194144),1 which was written and published during the war years in Zurich, Darmstaedters study was the product of reflection in exile. In one sense, namely in the systematic character of his challenge to the cult of the founding father of modern Germany, Erich Eyck had broken new ground in Bismarck biography. Like Darmstaedter a lawyer, Eyck wrote as a disappointed liberal, for whom Bismarck destroyed the Germany that might-have-been, a Germany in the tradition of Western European liberalism. To his contemporaries among German historians, notably the influential Hans Rothfels, author of more than a dozen publications on Bismarck, among them an edition of his speeches and letters, the particular merit of Eycks work lay in its being the first full-length biography of Bismarck the man and his career. However, Eycks vision of this other Germany was, in Rothfels view, simply utopian.2 In the English-speaking world of the 1950s and 1960s, Eycks intimate knowledge and understanding of the primary sources and of constitutional and administrative matters, together with his critical stance, gave his study the status of a standard work. Published in English in an abbreviated edition in 1950, Eycks Bismarck and the German Empire3 shaped judgement of the German Chancellor in North America and Britain long before the de-mythologizing of Bismarck by younger German historians took off in the late 1960s. The importance of Eycks Life in addressing the issue of continuity in German history, and in the historiography of German nationalism, of the Second Empire and its founder, Otto von Bismarck, remains uncontested. Its authors ideological stance has, however, inevitably dated his work.

Bismarck and the Creation of the Second Reich, which has endured for almost half in length4 and scope, formed part of, and was an early contribution to, the debate on the person of Bismarck and his responsibility for subsequent events which has endured for almost half a century. In his short introduction Darmstaedter declares that he only encountered Eycks work when he was well advanced in the writing of his own (xii). While broadly in agreement with Eycks position, he stresses that his work was specifically directed at a restricted section of the reading public, the English speaking world, and that its perspective was quite specifically that of Germanys collapse in 1945, which post-dated Eycks final volume by a year. Part of the context of Darmstaedters work was the publication, just one year after the collapse of Hitlers thousand-year Reich, of an epoch-making book-long essay: The German Catastrophe by the German historian of ideas, Friedrich Meinecke, in which he held modern German history to account.5 Thus in choosing the German term Reich rather than Empire for his title, Darmstaedter was clearly making a polemical point. His is a political biography, with little or no reference to those areas which feature so prominently in Bismarck biographies and studies of subsequent generations, namely society, the economy, and culture. He draws, as Eyck had done in greater detail, on the substantial body of official documents of the Bismarck years, the bulk of which were published after the fall of the German Empire in 1918, as part of the Weimar Republics legacy to the nation,6 and on Bismarcks own inimitable voice in his speeches and correspondence.7 One of its merits for students today is the authors use of older Bismarck biographies and the reminiscences of contemporaries, which are often forgotten in the voluminous mass of modern and contemporary Bismarck studies. Darmstaedters factual tone and fluent style makes the distant world of European politics and diplomacy, which dominated much of the history writing of his time, easily accessible to the modern reader. However, the ideological message informing the text is clearly evident, programmatically, not to say polemically, set out in the words of his Introduction (xii):

Does not the collapse of his work fifty-five years after he left the stage compel us to doubt his right to be called the greatest man of the age?

And in occasionally emotive language he describes what is left of that much-vaunted legacy as pitiable political plants which at present grow on the soil of what was once was Bismarcks Reichartificial flowers, for they are not the expression of political strength but of political impotence (x). At the heart of his argument lies the alleged relationship between Bismarcks creation and subsequent cataclysmic events which, with no doubt unconscious irony, he describes in biological metaphors:

The question with which we are mainly concerned is whether in Bismarcks creation of the Reich the essential germs of the disintegration which took place in 1945 were not only simply latent, but can be clearly discerned.

In the Third Reich, he goes on to declare: