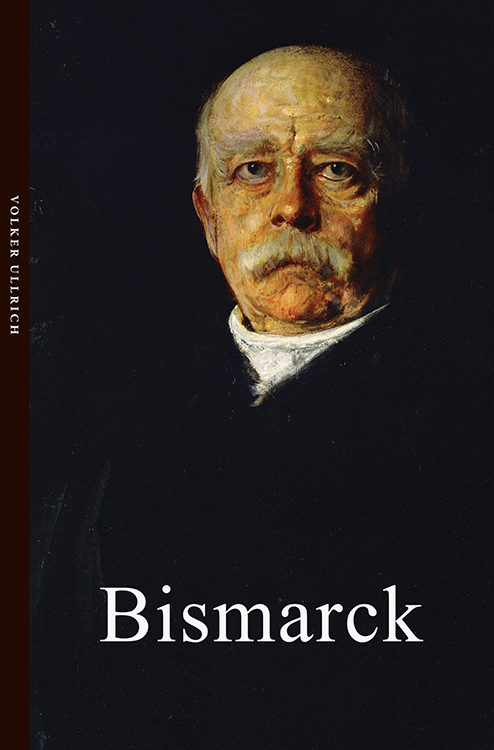

Bismarck

The Iron Chancellor

Volker Ullrich

With a Foreword by Prince Ferdinand von Bismarck

Translated by Timothy Beech

HAUS PUBLISHING LONDON

Contents

Foreword by Prince Ferdinand von Bismarck

Bismarck was neither the creator of German unity nor founder of the German Reich but it was he who re-established both. It is crucially important to acknowledge this political as well as historical conclusion in order to counteract the prejudice that Germany is the youngest and too lately established nation in Europe. Following the period of mass migration, the German people, together with the French, were the oldest people in Europe. Around AD 900 it had already achieved its political as well as national unity. As Bismarck said on 24 February 1867: There was a time when the German Reich was powerful, great and honoured because it was united and led by a strong hand. Its head and limbs share the responsibility for this Reich sinking into a state of disunity and impotence. However, the longing of the German people for their lost possessions has never ceased. The history of our time is the history of endeavours to win back for Germany and the German people their past glory! Bismarck was determined to satisfy this longing. This aim was his lifes work and it is almost incredible that he achieved it in such a short time.

Due to his innate sensitivity it was at an early stage that he realise the Germans longing for their lost unity. As Bismarck was, like Goethe, a man of both thought and action, his open declaration in the Reichstag on 9 July 1879 did not really surprise anyone: From the very beginning of my career I have had only this one guiding star: by which way and means could I lead Germany into unity and in so far this was achieved, how could I strengthen and support this unity and finally make it a result of the free will of all its participants?

He made it his task to re-establish the unity of the Germans which had been lost for centuries, and his ability to bring it about was due to his energy, sensibility, literary education and expressiveness. His extensive knowledge and his pragmatic understanding of history were a requirement for his well-considered, imaginative and, as far as possible, successful politics. According to the historian Ernst Engelberg, Bismarck grew to be a figure of historical importance whose understanding of the world and far-sightedness have ever since been fascinating his contemporaries as well as posterity.

The German Reich founded by Bismarck is even today to be seen as the foundation, standard and legal basis of all German policy. His Reich was an important and strong country but at no point predominant amongst the European states. Bismarck set the benchmark for succeeding chancellors by demonstrating how, in the middle of Europe, German foreign and domestic policy could be turned into a policy of peace for the whole of Europe. His social policy was also a model for many countries.

It is a statement in defence of his honour to hear the French ambassador in London at that time to arrive at the following conclusion: I am firmly convinced that as long as Bismarck is in control of the situation we can absolutely rely on German loyalty. But as soon as the chancellor resigns from his office, stormy times are going to come for Europe.

And finally it was Gustav Stresemann who said: It would be good to write a book on the misunderstood Bismarck in which it is shown that he was the one who at the height of his power was actually the most careful in making use of it and how he asserted himself in 1866 and 1870 against those who could not get enough of it. He wanted to keep the peace in Europe. This would be a better image of him than the one generally created by legend which shows him as a man in cuirassier boots.

Prince Ferdinand von Bismarck

October 2007

Introduction

Those who have possessed great political power for a long time and then suddenly lose it generally feel the urge to compose their memoirs not only in order to transmit to posterity as favourable a view as possible of their own achievement, but also so as to settle accounts with former political opponents. It was no different in the case of Otto von Bismarck after his fall. On 16 March 1890, one day after his definitive break with the young Kaiser Wilhelm II, he confided to a visitor: Now I am going to write my memoirs. Meanwhile, the Reich Chancellery was already piled high with boxes full of secret files that Bismarck, during the next few weeks, would have taken to Friedrichsruh, his place of retirement in the Saxon Forest outside Hamburg.

As his assistant, Bismarck chose Lothar Bucher, a former 1848 liberal whom he had appointed a councillor in the Foreign Ministry, where he served Bismarck faithfully. Without Buchers insistence, Bismarcks memoirs would probably never have been written. It was Buchers task to bring order to the chaos of this material, correcting the most egregious errors, and to make a publishable text out of mere fragments. The final product was very far from being complete in October 1892 when, in a hotel on Lake Geneva, Bucher died.

Up to his own death on 30 July 1898, Bismarck continually made small revisions to the already completed sections, without taking the work any further. The first two volumes of his Memories and Reflections were published by Cotta at the end of November 1898; the third volume, centring on Wilhelm II and the events surrounding Bismarcks dismissal, only appeared in September 1921, after the end of the Wilhelmine Reich. It proved more successful than anyone had expected. In the bookshops, noted Baroness Hildegard von Spitzemberg, people are coming to blows over Bismarcks memoirs [ ] The edition of 100,000 copies is long since out of print, and there is no way that Cotta can meet the continuing demand.

In his final years, Bismarck had become a living monument to himself, and his memoirs played no small part in exalting his historical importance into the realms of myth. They provided the orthodox view of Bismarck which dominated German historiography up to 1945 with an inexhaustible stock of quotations, and they shaped the image many patriotic Germans had of the founder of the first German nation-state Lesser German but Greater Prussian. For a long time this made it more difficult to form a sober, undistorted view of this figure who had such a large impact on German history. Though the literary quality of many sections of Bismarcks memoirs still continues to impress, as a historical source they should be used only with the greatest caution.

The idolisation of Bismarck that predominated for so long was matched by a demonising view, the other side of the coin; as the journalist Maximilian Harden remarked critically as early as 1896, this tended to depict him as a pitch-black, diabolically clever Machiavellian caricature, occasionally dressing up on a whim as a sulphur-yellow cuirassier. Modern historians, however, have moved away equally from both the positive and the negative legends. There are now three important Bismarck biographies, each of which in its own way represents a significant historiographical achievement.

Like Frederick the Great and Goethe, Bismarck is a figure we will never get to the bottom of. Really, everyone makes their own biography of such men as these.

HANS-JOACHIM SCHOEPS

The first of these, by the Frankfurt historian Lothar Gall, appeared in 1980. He was the first to succeed, with aplomb, in navigating between the Scylla of Bismarck worship and the Charybdis of demonising the German statesman, instead considering him critically within the terms of his own times. Gall sees Bismarck as someone with a great deal of influence on events who was nonetheless unable to control the changes he had unleashed, and an arch-royalist who wanted to preserve Prussias conservative political structures but who also did much to further the process of economic and social modernisation; in short, Bismarck was a white revolutionary Galls subtitle was borrowed from an essay by Henry Kissinger who, like the sorcerers apprentice, ended up being unable to master the powers he had summoned up.