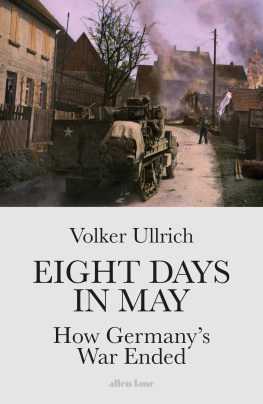

Volker Ullrich

EIGHT DAYS IN MAY

How Germanys War Ended

Translated by Jefferson Chase

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in German as Acht Tage Im Mai: Die letzte Woche des Dritten Reiches

This translation first published in the United States of America 2021

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2021

Copyright Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Mnchen, 2020

Translation copyright W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2021

The moral rights of the author and translator have been asserted

Cover image Glasshouse Images/Shutterstock

ISBN: 978-0-141-99411-6

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Also by Volker Ullrich

Hitler: Ascent 18891939

Hitler: Downfall 19391945

Preface

The Last Week of the Third Reich

On May 7, 1945, the German author Erich Kstner wrote in his diary, People walk through the streets, numbed. The short pause in history lessons makes them nervous. The gap between no longer and not yet bewilders them.

At the same time, these days were exceedingly dramatic. Sensation upon sensation! wrote a legal official from the western German town of Laubach in his diary on May 5. Events rush in! Berlin conquered by the Russians! Hamburg in the hands of the English! German troops in Italy and western Austria have surrendered. This morning the German armys surrender in Holland, Denmark, and Northwest Germany came into force. Disbanding on all fronts.

The process of dissolution happened so suddenly that contemporary observers had trouble orienting themselves and keeping abreast of events. Germanys dramatic collapse left many who lived through it with a feeling of disbelief, of having witnessed something fantastically unreal. Again and again, you take your head in your hands to convince yourself that all of this isnt a dream, remarked the pro-democracy politician Reinhold Maier from southwestern Germany on May 7.

Contributing to the confusion was the fact that the end of the war came differently to different parts of the disintegrating Third Reich, and people in each region perceived it in divergent ways. Whereas in the west the Allies were often welcomed as liberators, fear of the Soviets prevailed in Germanys eastern provinces. This was partly because for years the Nazis had cultivated an image of the Bolsheviks as mortal enemies and partly because Germans were aware of their own crimes against humanity in Hitlers genocidal war against the Soviet Union. While many German soldiers more or less voluntarily surrendered to the British and Americans, the Wehrmacht continued its fierce resistance to the very end against the Red Army in the east. Hamburg was handed over to British forces without a fight on May 3 while German soldiers kept trying to defend the so-called fortress city of Breslau (todays Wrocaw) until May 6. Even as liberated cities and regions in Germany were taking the first measures to rebuild political life, the German occupation of parts of the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway continued into the first days of May. In the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the German occupation did not end until the insurrection in Prague on May 5.

Notwithstanding many Germans subjective perception that time had come to a halt, the first days of May witnessed frantic activity in the streets. Huge masses of people were on the move. Death marches of concentration-camp inmates crossed paths with retreating Wehrmacht units and groups of refugees; columns of POWs encountered those of liberated slave laborers and bombed-out people returning home. Allied observers spoke of a veritable migration: British diplomat Ivone Kirkpatrick compared all the movement to a giant anthill that had been disturbed. One of the main ambitions of this book is to depict this chaotic and often contradictory sequence of events.

Essential to the intermezzo from April 30 to May 8 was Karl Dnitz, the grand admiral whom Hitler named as his successor, and his regime in the northern German city of Flensburg. Dnitz was responsible for the war continuing for a full week after Hitlers suicide. The admirals strategy of partially surrendering in the west while fighting on against the Soviet Union in the east was intended not just to allow the greatest number of German civilians and soldiers to flee behind British and American lines, but also to sow discord within the anti-Hitler coalition. One of the narrative threads of this book examines how Dnitz sought to turn this strategy into reality, the steps he took, and the illusions under which he labored.

The short-lived Dnitz government is also instructive because it featured an almost uncanny continuity with the Nazi regime in terms of both its personnel and ideological statements. Dnitz and his ministers showed no willingness to take responsibility for the crimes against humanity the Nazis had committed. In this regard the governments attitude was typical not just of the entire Nazi elite but also of large segments of the German populace.

Yet as the final remnant of autonomous German statehood, the Dnitz government influenced only a small portion of events in those fateful eight days. Thus, this book trains its sights far beyond the narrow confines of the Flensburg enclave. The aim is to provide a broad panorama of major political, military, and social events and developments: the final military battles; the death marches; the suicide epidemic at the end of the war; the continuing horrors of German occupation for foreign peoples; Germans own first encounters with their occupiers; the mass rapes in Berlin; the fate of POWs of various nations, concentration-camp inmates, and displaced persons; the early, wild expulsion of Germans from parts of Eastern Europe; everyday life among the ruins of war; and the tentative new beginning for the German people and the start of meteoric postwar careers for some among them.

The events described here had causes stretching back into the past and consequences reaching well into the future. For that reason, this book repeatedly travels beyond the boundaries of those eight days. Further, the book traces the origins and careers of its main protagonists. Biographical miniatures alternate with historical closeups. The aim is to create a vivid portrait of the dramatic transitional phase between the apocalyptic demise of the Third Reich and the beginnings of the Allied occupation.

This book allows historical eyewitnesses to be heard in the words of their own diaries, correspondence, and memoirs. In particular, daily journals are an essential source because they most directly express the ambiguous experiences of the end of the war. They reflect the contradictory sensations and feelings of early May 1945: the impression of apocalypse on the one hand and of a new beginning on the other.