Mohja Kahf

Acknowledgments

Many people have read and responded helpfully to the manuscript since it began in 2001 as a thirty-page piece called Hennad Hoosiers, and then became Greetings from Islamistan, Indiana, before getting its present title. I am grateful to my daughters, Weyam and Banah, who are my finest and most hard-to-please critics, for whom the original vignette was written, and to Iffat Renae Quraishi, Dr. Asifa Quraishi, Zeynab Ahmed, Dr. Yemisi Jimoh, Abdal-Hayy and Malika Moore, Patricia Dunn, Michael Muhammad Knight, Pamela Taylor, Ginny Masullo, Brenda Moossy, Alison Moore and my classmates in her 2002 writing workshop, Molly Giles, Freda Shamma, Afeefa Syeed, Nadifa Abdi, Dr. Fatima AbuGideiri, my brother Usama Kahf, Carmen and Darrel Davis, Kristi Arford, Cherri Randall, all the students in my Muslim American Literature course of Fall 2005, Leslie Berman Oelsner, Rachel Stubblefield, Rahat Kurd, and Z.S., who does not want to be named. Merci a Dr. Nancy Arenberg et Louise Rozier, and to Judith Levine. I am grateful to Patty Lebbing, Chad Andrews, and Sheila Nance for office help, and to the folks at Postal Center Plus, whence I have good luck mailing manuscripts. Thanks also to the myriad people of goodwill whom I plied for information about life in Bloomington, Turkish cigarettes, entomology labs, and tons of other things I had fun researching. Loving thanks, always, to Najib for holding down the fort so I can pursue the muse. The women who cared for my baby while I wrote have my tender gratitude: Kate Conway, Carmen Davis, Joy Caffrey, Hamsa Newmark, Kelley O'Callaghan. To the editor, Michele Slung, I owe enormous thanks for finding the story amid the clutter, and to Adelaide Docx at Carroll & Graf for her work in the final stages. The flaws that remain are due to my inordinate failings and not for lack of good help.

I am grateful, also, to the beautiful crowd of authors, living and long gone, whose points of inspiration to me may, if I am lucky, be discerned here.

... my creative life is my deepest prayer...

-Sue Monk Kidd, The Dance of the Dissident Daughter

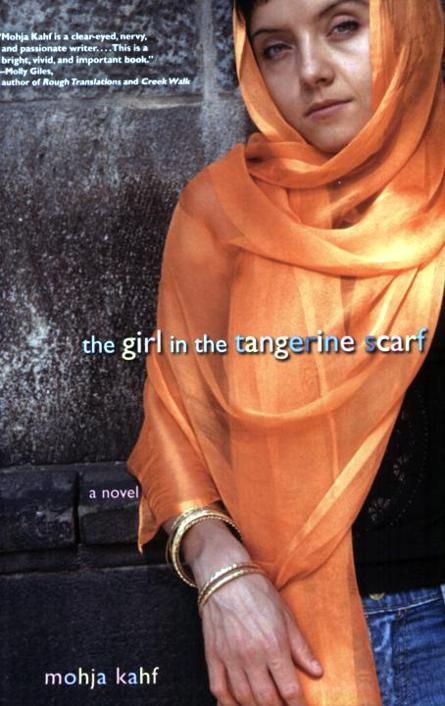

"Liar," she says to the highway sign that claims "The People of Indiana Welcome You." The olive-skinned, dark-haired young woman drives west on the old National Road. A small zippered Quran and a camera are on the hatchback's passenger seat in easy reach, covered by an open map-States of the Heartland. Khadra Shamy spent most of her growing-up years in Indiana. She knows better than the sign.

She passes over the Whitewater River, bracing herself. Here comes the unbearable flatness of central Indiana. She has the feeling that the world's been left behind her somewhere, in the final stretches of Pennsylvania, maybe, where the land had comforting curves. Out here there seems to be nothing for the eye to see. Strip mall, cornfield, small town main street, Kmart, Kroger, Kraft's, gas station, strip mall, soybean field, small town main street, Kmart, Kroger, Kraft's, strip mall. All blending into one flat sameness.

There are silver silos and pole barns, tufts of goldthread on the meridian, and the blue day beginning to pour into the dark sky. But it is not mine, she thinks, this blue and gold Indiana morning. None of it is for me. Between the flat land and the broad sky, she feels ground down to the grain, erased. She feels as if, were she to scream in this place, some Indiana mute button would be on, and no one would hear.

And the smell, she thinks, getting out at Glen Miller Park to pray fajr on the grass near a statue labeled Madonna of the Trail. God, what is it? She has forgotten it, living for years away. There is a definite smell to the air in Indiana. It's not pollution; not a bad odor, really-nor a good one; just there. Silage, soybeans, Hoosier hay, what? she asks the Madonna after salah. The stone Madonna in a bonnet, holding a baby in her right arm, a little boy clinging to her skirts, peers stonily into the distance.

"No checks no credit no credit cards." Khadra buys antacid and a postcard of the Madonna of the Trail: Greetings from Richmond. Eyeing the postcard, she thinks: sloppy work. I could do better. Peering into the tarnished restroom mirror, she examines her face. Her forehead is high, with a Dracula's peak, and a bit of grass has matted to it from prostration. She brushes it off.

Gray-black pieces of a busted tire flap in the lane in front of her as she gets back on the road. A faded woman in a backyard adjacent to the highway hangs a large braided rug on a rope. Khadra sees a sign for the "Centerville Christian Church." Isn't that redundant? she wonders. Like "Muslim Mosque?" "... of Bosnian leader Alija Izetbegovic', in war-torn former Yugoslavia.... "" .. traffic heats up as racecar fans converge on Indianapolis this weekend.... "And then, finally, some music: Sade pouring out "Bullet Proof Soul."

Khadra glances sideways at fields of glossy black cows. A sign flashes, "Mary Lou and Mother, Rabbit Foot Crafts," but Khadra does not slow. Stimpson Grain Drying Corp. "100% American," a sign advertises-what, she doesn't know. Burly beardless white men in denim and work shirts sit in front of a burned-out storefront. The giant charred store sign, Marsh's, leans against a telephone pole. Possibly their only grocery for miles. The men's loose jowls have the cast of a toad's underbelly. She feels them screw their eyes at her as she drives past, her headscarf flapping from the crosscurrent inside the car. She rolls the windows up, tamps her scarf down on her crinkly dark hair, and tries to calm the panic that coming back to Indiana brings to her gut.

A little girl's face appeared, a girl with dark hair and a high forehead. She peeked out from between the swaying bed linens-vined, striped, and flowered-alive on clotheslines. Tucked in the elbow between two buildings in the Fallen Timbers Townhouse Complex, the laundry corner was little Khadra's hideout. Ruffled home-sewn nightgowns became Laura and Mary Ingalls racing Khadra along the banks of a prairie creek. Quivering calico blouse sleeves brushed against her as train brakes whinnied in the distance. Daddy longlegs moved from crevice to crevice in the bricks of the bordering buildings. Old Father Long-legs, wouldn't say his prayers, take him by the left leg, and throw him down the stairs. Khadra followed them, fascinated. Picked up fat jewel-box caterpillars with white, yellow, and black stripes. Touched a potato bug, which cringed and curled into a ball, world within worlds.

Her mother always ran the laundry twice in the Fallen Timbers basement laundry room with the coin machines. Because what if the person who used the washer before you had a dog? You never knew with Americans. Pee, poop, vomit, dog spit, and beer were impurities. Americans didn't care about impurities. They let their dogs rub their balls on the couches they sit on and drool on the beds they sleep in and lick the mouths of their children. How Americans tolerate living in such filth is beyond me, her mother said. You come straight home.

Sunshine filtered through the fabric forest. Khadra thrilled to its flutter of secrets and light, its shuttering and opening motions. Suddenly it revealed a boy with heavy pink flushed cheeks on a dirt bike, tearing through the hung laundry, pulling down rope, soiling sheets with his tire tread. Khadra ran. Screamed and ran. Fell, scraped her cheekbone on the cracked asphalt. He wheeled and turned. Gunning for her.