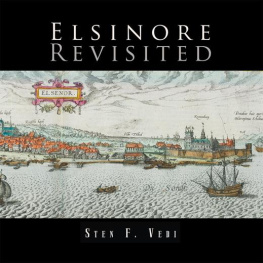

Elsinore Revisited

Shakespeares and Hamlets Danish connections re-examined

Copyright 2013 by Sten F. Vedi. 303118-VEDI

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012901668

ISBN: Softcover 978-1-4691-5905-8

Hardcover 978-1-4691-5906-5

EBook 978-1-4771-0285-5

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission

in writing from the copyright owner.

Rev. date: 03/19/2014

To order additional copies of this book, contact:

Xlibris LLC

0-800-056-3182

www.xlibrispublishing.co.uk

Printed with contribution from The Gyllenstierna Krapperups Foundation

Contents

Elsinore Revisited

This Ientleman of Polonia: Polonius, a Character in Disguise

Sten F. Vedi

To Marianne

According to the dominant tradition, William Shakespeare from Stratford upon Avon wrote Shakespeare. His name was printed on the title page of the majority of the works which we know as Shakespeares canon, and he is also referred to in other contemporary textual sources. It is difficult and almost impossible to explain away why Shakespeares name occurred in those texts, which apparently are independent of each other, if he was not the author. For a review of the textual sources, the reader is first and foremost referred to a recent book by James Shapiro, Contested Will. It is a book with well-balanced arguments for and against the different candidates, who, according to various supporters, aspire to the authorship. The discourse is as objective as can be expected, and it is free from emotional attacks which have been characteristic of the opposing parties in their struggle for supremacy of one candidate over another. After an enlightening analysis of the various candidates claims to be the author, Shapiro argues logically and convincingly in favour of Will from Stratford, primarily on the basis of the mentioned textual sources. It is hard not to be carried away by his arguments, and I dare not challenge his main conclusion, yet.

However, things are not always as simple as they appear to be. Maybe the authorship is more complicated. Is it correct to give Shakespeare credit for being the sole author? If there was someone else who created the plot and characters in Hamlet , as well as the site-specific dramatic scenes, would he not be an essential collaborator? In spite of the verdict passed on the above-mentioned basis of textual evidence, there are circumstantial pieces of evidence which make me uneasy as to whether we know the whole truth and nothing but the truth about the authorship. These are, for example, evidence related to the case of Polonius as well as site-specific knowledge in the play about Denmark and Elsinore. This evidence contradicts, at least partially, that William Shakespeare might have been the sole author of Hamlet . We know him to be a prominent shareholder in the Lord Chamberlains Men and the Kings Men. The latter succeeded the first-mentioned group. Is it possible that there were more hands on the manuscript(s), all of which are lost? In the same way, as there was a shared ownership of theatres, there may have been a consortium of writers behind the many plays, and that one person in this case and other cases was the responsible author, i.e. a person who by agreement with the others represented them in different relations to the theatre, the Master of the Revels and the London Stationers Company.

The notion that there might have been more hands and minds behind Shakespeares plays is not absent in Shapiro Brian Vickers, who took delight in mocking editors who had ignored these studies or continued to insist in defiance of the evidence that Shakespeare had worked alone. The question of collaborative authorship is in this connection related to later plays such as for example Pericles, Henry the Eighth, the Two Noble Kinsmen, Titus Andronicus and Timon of Athens, which probably were co-authored by Wilkins, Fletcher, Peeles, Middleton (in the order mentioned). Shapiro even refers to rare glimpses we get of how playwrights may have cooperated in the Elizabethan and Jacobean era such as [in] Nathan Fields letter in 1614, pitching a new play to Henslowe, where he writes that Daborne and I have spent a great of time in conference about this plot, which will make as beneficial a play as hath come these seven years. Shapiro goes on to state that

One of the great challenges, then, to anyone interested in the subject is that we know so little about how dramatists at the time worked together. We just know primarily from Philip Henslowes accounts of theatrical transactions from 1591 to 1604 that they did, and that in the companies that performed in his playhouses, it was the norm, not the exception. But it is risky to extrapolate too much from that evidence how Shakespeare himself worked. And it seems obvious that collaborations during his early years were significantly different from those after 1605

If we accept the challenge, it is not necessary to resort to theories and allegations of conspiracy from one or the other parties in the authorship controversy when investigating and trying to explain the phenomenon of collaborative authorship or division of labour. It remains, however, to be seen if this was a practice around the earlier works we know as Shakespeares plays and poems. A closer analysis than mine is necessary, as mine is more of a hypothetical nature built as it is on circumstantial evidence related to someones familiarity with Denmark. A renewed analysis of literary style, linguistic markers, sociolinguistic traits, plot and characters, dramatic structure, as well as the social perspective of the plays, to mention a few aspects, have to be called upon.

Vickers thinks that since collaborative authorship was standard practice in Elizabethan and Caroline drama, it would be extremely surprising if Shakespeare had not shared this form of composition. He goes on to list eight plays where Shakespeare took part in joint authorship ( Henry VI, Edward III, The Book of Thomas More, Titus Andronicus, Timon of Athens, Pericles, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and Cardimo [now lost]), all of which are later plays. I shall not try to enlist Vickers as a possible supporter of my theory about a joint authorship of Hamlet . However, it is tempting to play with the idea, knowing that Elizabethan men of letters often shared in composing a play. As there are many ingredients of collaborative and joint ownership, it is my supposition that someone else than Shakespeare contributed to the plot and the portrayal of the characters. Those characters were recognizable to the Elizabethan society. Given the state of the documentary sources, we shall never know for certain who the collaborative authors were or how and why the arrangement was established. Neither is it probable that new evidence will come to the surface after centuries of search through archives, both public and private. So what I offer is a description and interpretation of some peculiar circumstances linked to the character of Polonius (alias Henrik Ramel), to the site of Elsinore, to the Danish Court, and to the Kingdom of Denmark. I am mainly concerned with the authorship of Hamlet . But the subject matter opens up a broader perspective on authorship in English Renaissance drama.

The reader may wonder why we should bother about the authorship of Hamlet . My answer to this is simply that if we know who the author(s) were, that knowledge could add something to our understanding and the interpretation of the plays. The key questions in this respect are: What did the works mean to the Elizabethans and Jacobethans when they were first performed and what do they mean to us today? My focus is on the question of what certain aspects of Hamlet meant to the audience, the Elizabethans, when it was first performed.

Next page