Contents

Guide

Page List

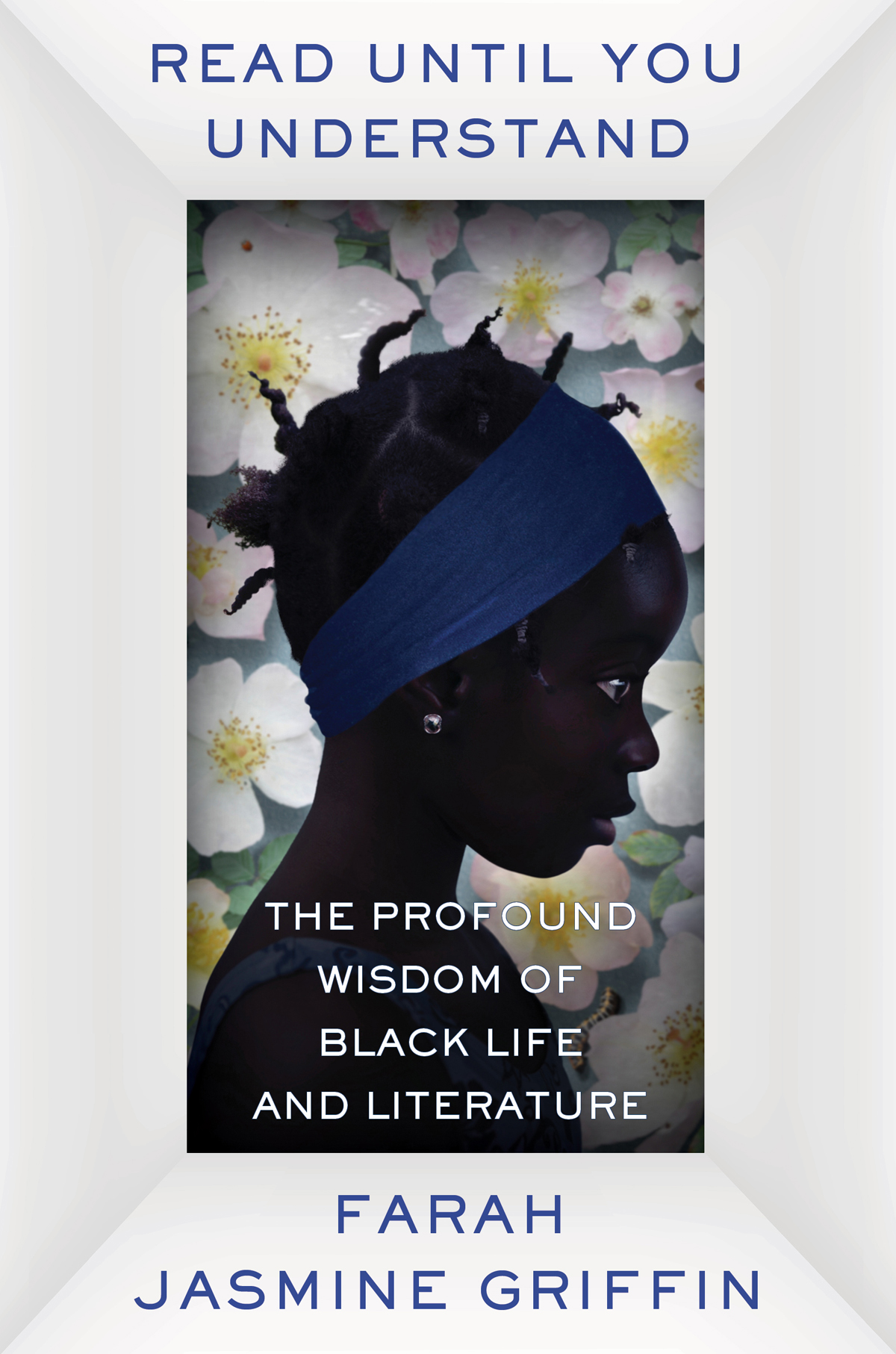

READ

UNTIL

YOU

UNDERSTAND

The Profound Wisdom of Black Life and Literature

FARAH JASMINE GRIFFIN

For T.M.

CONTENTS

This book begins with a girl and ends with grace. Along the way, through a combination of memoir and readings of African American literature, it touches upon the question of mercy, the elusive quest for justice, the prevalence of beauty, even in the presence of death, and throughout, hope in the face of despair.

Both the autobiographical reflections and my readings of the literature speak to the ideals and failures of the U.S. experiment with democracy. My goal in writing this book is to draw upon a lifetime of reading and almost thirty years of teaching African American literature to explore how, in addition to addressing concerns about democracy, perhaps even more than these, the works also speak to ideas and values that have concerned humanity since the beginning of time. Within these pages, I seek to share a series of valuable lessons learned from those who have sought to better a nation that depends upon, and yet too often despises, them. In the process, they have changed the world.

I am guided by the following questions: What might an engagement with literature written by Black Americans teach us about the United States and its quest for democracy? What might it teach us about the fullest blossoming of our own humanity? What I offer here is a series of meditations on the fundamental questions of humanity, reality, politics, and art. Each chapter addresses a specific body of work and the issues it raises. Although you do not have to have read the books I discuss in order to grasp the lessons I share, I hope my words will entice you to pick up these works and read them. To do so will only enrich your experience, understanding, and life.

The voices that denounced chattel slavery, that spoke to the promise of meaningful freedom, that voiced pleas for justice which made the constitution a living document, the promise of which one day could be made real, have much to teach us. But even more than this, these works speak to us beyond the narrow boundaries of race and nation. They explore timeless values that guide us, reminding us of our responsibility to ourselves and others.

All Americans, indeed all freedom-loving people, should have exposure to and an understanding of this body of work. It reminds us of paths taken that should be avoided and paths not taken that may have yielded different futures. It encourages us to learn the bitter truths of our history as well as the transcendent beauty and humanity of some of our responses to it. This strikes me as especially urgent, now more than ever, when so many Americans appear ignorant of our history and of the importance of the democracy they claim to revere.

In the questions that I raise throughout these pages, I have been deeply influenced by a lifelong intellectual, aesthetic, political, and spiritual engagement with the writings of the late Toni Morrison. Informed by her writing, I ask a series of questions of selected works by Black writers. The authors do not posit or forward a system of ethics, but they do seem to bear witness to one that emerges from the community about whom they write.

In the midst of a hostile society, a society that wants our labor or our death, we live in pursuit of justice, in pursuit of freedom, and longing for a bit of grace. How shall we live, how shall we treat each other, how shall we treat our compatriots, some of whom are guilty of crimes against us?

Each year a multiracial group of students take my class, and each semester they encounter ideas that challenge their understanding of themselves, their relationships to each other, and what they thought they knew about the nations history. They are forced to rethink their notion of what the United States is and their place within it and within the world. It is my hope that readers of this book will have a similar experience. And, along the way, I hope that they, like my students and myself, will take pleasure in the brilliance and the beauty of the literature.

Through the meditations presented within these pages, I think we will learn that writing by African Americans holds many important lessons for all people interested in the survival of this fragile democracy and the planet on which it exists.

A NOTE ON STRUCTURE

Read Until You Understand is structured around specific concepts, themes, and ideals. These have been chosen from a myriad of possibilities because they most consistently emerge in literature written by Black American authors. They also have the potential to transcend the differences that divide us. All people feel despair, long for love, create beauty, and face death. I have not organized the chapters chronologically as I might do for a literary survey. Instead, the book is designed as a seminar where we readers, together, seek a deeper understanding of the works and the principles they explore. Works written in different periods are placed in conversation with each other to demonstrate both consistency and change over time. Each chapter provides an autobiographical meditation that may be informed by some mixture of history, philosophy, or politics. Read Until You Understand demonstrates how a people have lived with style, grace, brilliance, and beauty in the face of persistent crisis and catastrophe. This is one of the many underappreciated gifts of Black Americans to the nation they have helped to shape and build. In fact, because of them, it is one of this nations greatest gifts to the world.

I began writing this book shortly after the 2016 presidential election. I finished it in the midst of a global pandemic and a glorious uprising that seeks to advance Black freedom. Throughout this time, the stories that I tell, the literature that I share, and the values it explores remain urgent and necessary.

READ

UNTIL

YOU

UNDERSTAND

M y formal study of African American history and literature did not begin until college. My love of them began much earlier, with my father, who believed teaching was an act of love. Because I adored my father and cherished being with him, I experienced learning as love. A natural-born storyteller, he would make our weekly visits to the public library, bookstores, and many of Philadelphias historic landmarks come alive. The history of the nations founding was more than a rendering of facts. Through my fathers eyes it became an epic tale of bold and courageous characters challenging stuffy old men in Europe. His tellings were cinematic in their sense of adventure. An old fedora became a tricornered hat like those worn by the eighteenth-century Philadelphians who changed the course of history. On days off from his job as a welder at the Sun Shipbuilding Company in Chester, Pennsylvania, after work and on the weekend, he took me to Philadelphias Elfreths Alley, the nations oldest residential street, to Independence Mall, and to the various sites that surround it. He purchased copies for me of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, which were reproduced on parchment paper for tourists and history buffs. Before I started school, he had me memorize and recite the Preamble to the Constitution, the opening of the Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address, and the Presidents of the United Statesall the skills he had learned as a Philadelphia schoolboy during the Depression. He followed my recitations with questions. What do you think that means? Lets look up that word and use it in a sentence. This was not a practice he reserved for me, nor did he do it out of recognition of my intellectual precocity. My cousins, my older sister Myra, and her children all received the same instruction.