SH

For Shonaleigh and Isaac

Ive telled my tale,

Thee tell thine.

***

DB

In memory of Roy and Reg

Wordsmiths, fibbers, allotment enthusiasts,

and keepers of forgotten lore.

May these words prompt many questions

from the grandchildren you never met.

When the legends die, the dreams end;

there is no more greatness.

Attributed to Tecumseh (17681813), Shawnee chief

C ONTENTS

In June 2012, the Sheffield band Reverend and the Makers appeared live on BBC Breakfast Time , to promote a new release. The presenter, Bill Turnbull, was curious about this successful bands reluctance to relocate to London. What was it about their Sheffield home, he asked frontman Jon McClure, that made it so special?

McClure did not hesitate.

Understatement, he replied firmly.

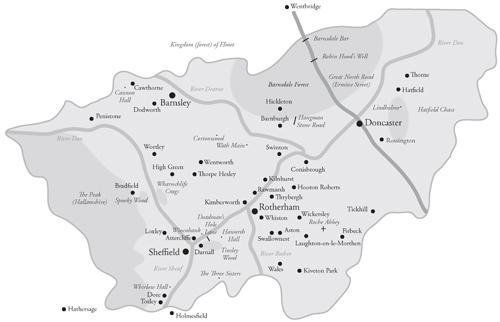

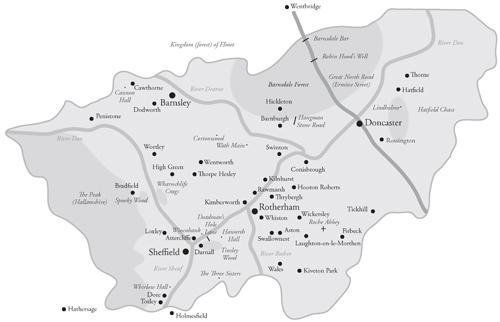

Understatement seems to run deep in South Yorkshire. For much of its history, the place hardly existed in official terms. An old name, Hallamshire , refers to a loosely defined area on the right bank of the River Don, but the southern reaches of Yorkshire were always part of its West Riding. The county of South Yorkshire, comprising the metropolitan boroughs of Barnsley, Doncaster, Sheffield and Rotherham, was created in 1974. It now appears as a historic centre of mining, metalworking and other industries, garlanded by legend-rich beauty spots, including the Peak District, the Yorkshire Dales, the Vale of York, the North York Moors, and Sherwood Forest, which can seem to outshine its own wealth of landscape, tradition and history. The understatement, however, is deceptive.

Traffic along eastern Britain has always had to skirt round the head of the Humber, fording or bridging its tributaries. The landscape drained by these smaller rivers including the Don, Dearne, Sheaf, and Rother forms a natural barrier to northsouth traffic. It is therefore no coincidence that local historians have long recognised the area now known as South Yorkshire as a frontier zone. Nor is it chance that the frontier has lasted longer than any of the territories and peoples it has divided. It has separated prehistoric tribe from prehistoric tribe; Celt from Roman; province from province, in Roman Britain; Dark-Age Briton from Dark-Age Saxon; and medieval English from conquering Vikings. Today, the same boundary divides the northern English county of Yorkshire from the counties of the English Midlands.

This durable frontier has, in turn, left its own marks on the landscapes that defined it. The name of the village suburb of Dore means, as it sounds, a door, or threshold. According to the great nineteenth-century folklorist Sidney Addy, the River Sheaf, which gives Sheffield its name, bears a name that similarly means boundary. The Red Lion Inn at Gleadless is still said to straddle the county line, and the stream that marked the county boundary, the Shirebrook, ran through the pubs cellar. Legend reports that late drinkers in modern times would cross the room to avail themselves of Derbyshires more liberal licensing hours.

But, paradoxically, the main thoroughfare of eastern Britain has always run right through the area. Over the centuries, the main route seems to have oscillated, like a gigantic plucked bowstring, up and down the Don Valley: from the Ermine or Icknield Streets that the Romans paved, to the Great North Road (now the A1) that Robin Hood watched, and back today to the route of the M1.

So South Yorkshire has always been so to speak less ancient boundary than ancient checkpoint. Such places tend to be fought over. Sheffields history began with Celtic and Roman fortresses, overlooking the lower Don river crossings. In 1966 archaeologists announced that earthworks at Butchers Orchard, North Anston, were, in fact, the remains of a medieval house, or maybe some seventeenth-century fishponds. There was disappointment in the local community at this announcement, because the earthworks had long been regarded as marks of an ancient battlefield. In context, this was a fairly reasonable supposition.

The terrain is hilly towards the west and flatter towards the east. Heath, woodland and wetland form its natural cover. Sheffield, indeed, remains one of the leafiest cities in Europe. The regions first prehistoric farmers largely kept to the uplands; later, when the wildwoods were cleared, the plough conquered the valleys. But throughout the Middle Ages there remained a great deal of managed hunting reserve: that is, forest , in the original sense of the word outdoor playgrounds for the rich, sometimes, but not always, thickly wooded. We read that Barnsdale, Robin Hoods favoured haunt, was not a forest in this sense, but was instead a remote tract of waste woodland. Sherwood, by contrast, was, legally, a forest. It existed as such by 1130 (Mitchell 1970: 16). There were many other forests and chases nearby, partly because local princes and great landowning families dominated the areas early history. Then came the medieval church, and the great landowning abbeys of Roche and Beauchief.

But when these great abbeys were ruins, South Yorkshires rivers began to lend water-power to the knife-grinding and metalworking trades, and the areas centre of gravity shifted westward back towards them, from the medieval towns of Conisbrough and Doncaster to the well-watered hills. From the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries, Sheffields Cutlers Company came to preside over a self-reliant, well-organised, confident and cohesive working community, whose backbone was the independent craftsmen, or little mesters, whose tradition of workmanship has lasted till the present day just about. Thereafter, industrial production in the area was destined to be organised on an even larger scale. Wood- and then coal-burning industry created substantial working and middle classes. Later, trade unionism inherited the areas old instinct for social cohesion and tight community. Other expressions of the same instinct, meanwhile, took many forms. In the earlier 1800s, in most English cities, blind street musicians were buskers or beggars, but in Sheffield they were an organised and prosperous guild, a central pillar of the rapidly burgeoning urban community. The sinking of pits and the spread of pit villages across the coalfields a recent process, not complete until well into the twentieth century sealed modern South Yorkshires character as an industrial centre. The countys central place in the modern labour movement lately expressed in an unofficial and affectionate title, the Peoples Republic of South Yorkshire was therefore grounded in old community traditions.

Well indeed were those old traditions called radical . Sheffield town stood with Parliament in the Civil War. When Royalists dug themselves in at Sheffield Castle, the castle was captured and razed. Little trace of it now remains above ground. In the 1790s, Sheffield would throw a street party, and roast an ox to divide among the city poor, whenever the revolutionary French armies won a battle (Mather 1862: xx). In the Yorkshire coalfields, the miners old enemy, Winston Churchill, was never quite accepted as the irreproachable figure he is often presumed to be elsewhere. In more recent times, community activism saved a Sheffield suburb, Walkley, from demolition, and also stopped the construction of an inner-city bypass through the suburb of Heeley; Heeley City Farm was created instead. Most spectacularly, there were the miners strikes, culminating in the great strike of 198485. The coalfields celebrated unabashedly when Margaret Thatcher died in 2013. It is easy to feel that Robin Hood of Barnsdale would have done likewise.

Next page