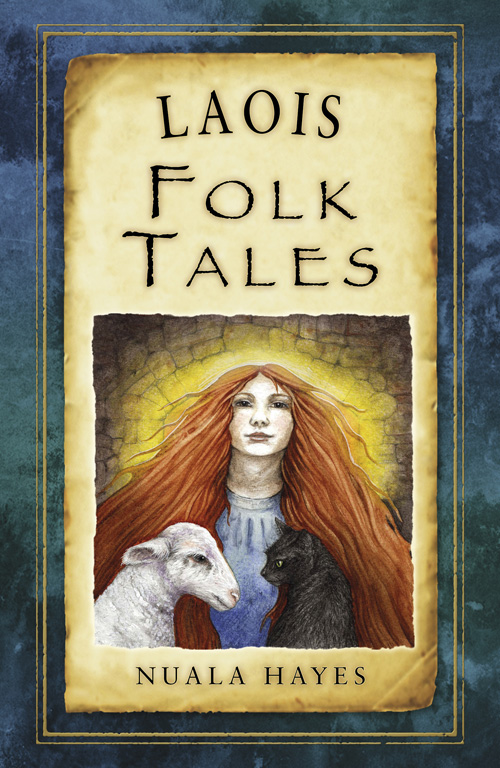

This work is dedicated to the people of Laois

C ONTENTS

Sometimes folklore cuts straight to the heart of life. It illuminates history like a small pure flame burning in the darkest corner of memory.

Vincent Woods, writer and broadcaster

I learnt about Laois mainly through the stories and lore that were shared with me when I had the good fortune to be appointed artist-in-residence with Laois County Council Arts Office in 2002.

My brief was to unearth the oral stories in this midland county, which, up to that point, were relatively unknown to me. To those who live on the peripheries of the island, the Midlands are places you pass through to get to the other side. The midpoint, the centre where roads meet, is also a place of movement and action, and a historically strategic place to possess, if the aim was to conquer. I discovered in County Laois that the stories that are told are intrinsically bound up with the landscape, the place and the history. The stories of ghosts and spirits are stories from the subconscious underworld, beyond the seen world. Many of the storytellers I met call themselves historians, yet they fully understand the purpose and value of the told story as a way of knowing the world and their place in it.

Henry Glassie makes the point in Irish Folk History that the local historians connect to an ancient and vital Irish idea by ordering history more in space than in time .

By the end of my time in County Laois almost two years and many stories later I had collected and recorded nine CDs of oral stories and history from many parts of the county. These recordings are now part of the Laois Oral Archive Collection and are available to the public through the Library Service. Some of those people who so generously shared their stories are no longer with us, but their voices remain. The recorded material was also the basis for a six-part radio series called Tales at the Crossroads , which was produced in 2004 for RT Radio One.

Thanks to the encouragement of Muireann N Chonaill, the Arts Officer, and with support from the Heritage Office, I also produced a video of the same name which was filmed by local artist Ray Murphy and edited by S Merry Doyle of Loopline Films.

A story told is never the same twice. The written word pins the story down and forces it into the straitjacket of sentences and grammar. And the written text cannot always capture the music of the voice, the pauses, the emphasis to make a point, or even a joke. Or can it? In retelling these stories in written form, I have tried to retain the voice of the person who told me the story. As a teller of stories myself, I found it difficult to write them down, but I resisted the temptation to change or improve them. To tell a story is to live in the moment along with a listener. To read a told story is a very different experience. A story asks to be told aloud.

The much-repeated phrase at the end of a story also applies here: M t brag ann bodh, n mise a chum (If there is a lie in here, dont blame me I didnt invent it!).

However, this time around, I had access to the riches of the National Folklore Collection at UCD, to the local libraries in Stradbally and in Portlaoise, and to the published work of people such as Laois archaeologist Helen M. Roe, who collected Tales, Customs and Beliefs from Co. Laoghis in 1939; John Canon OHanlon, who wrote the mammoth work A History of the Queens County , as well as collections of folk tales and local legends, which were published under his pseudonym, Lageniensis. Brother Dan Hassett FSC of the De la Salle Order in Castletown also collected and collated local lore and stories in 1985.

The collection of John Keegans Selected Works , edited by Tony Delaney, is always a rich source of stories and poems from his short lifetime (18161849). A History of Stradbally Co. Laois , compiled by the Stradbally Historical Project in 1989, was also very useful.

However, the real pleasure in the process of compiling this work was meeting the very generous people who shared their time and their stories with me first, in 2002 and now thirteen years later in 2015.

Grateful thanks to Paddy Heaney, Paddy Dooley, Mick Dowling, Michael Clear, Dan Culleton, Johanna ODooley, Adrian Cosby, John F. Headen, Roghan Headen, Arthur Kerr, Hugh Sheppard, Paddy Laffin, Tina Mulhall, Sen Murray of Laois Archaeology, Hugh ORourke, Jimmy Fitzpatrick, the past pupils of Camross National School and the families of the late Jenny McGlynn and Frank Fogarty, for allowing me to reproduce their stories.

I am grateful to the management and members of Laois County Council; to Arts Officer Muireann N Chonaill, and the staff at the Arts Office, to Heritage Officer Catherine Casey and to Bernie Foran, County Librarian, for their support and enthusiasm for the project. It was a great boon to stay at the Arthouse in Stradbally, so close to the beautiful hills and lush valleys, which feature in many of the stories.

Julie Shead, librarian at Stradbally Library, thank you.

Mle buochas to Criostir Mac Crthaigh of An Roinn Baloideasa/Department of Folklore at UCD for his help sourcing material and to storyteller Aideen McBride, without whose encouragement I might never have begun. Thanks also to my friend and colleague, Jack Lynch for perusing the manuscript with a beady eye.

I am delighted to collaborate once more with Rita Duffy, who provided such vibrant images to illustrate the stories. Folklore and story is a rich source of inspiration to her as an artist, and her enthusiasm and energy keeps me spinning on. Thanks also to the photographer Stanislav Nikolov who documented all the drawings.

Nuala Hayes, 2015

Rock of Dunamase, County Laois.

N OTE

. Vincent Woods, Folklore and Modern Irish Writing , Eds Anne OConnor and Anne Markey (Irish Academic Press, 2014).

The mythical origins of the Laoighsigh, the people of Laois, tells us that they were descended from the great Conall Cearnach, renowned among the Red Branch Knights and leader of the army of Conor Mac Neasa, King of Ulster, whose headquarters was at Emain Macha, now known as Navan Fort, in County Armagh.

It was said that Conall Cearnach fought against Queen Maedhbh of Connacht for seven years. After his defeat at the Battle of Ros na R alongside the River Boyne, he came south. The Book of Leinster tells us that he had two sons, Iriel Glnmhar and Lughaidh Laoiseach Ceann Mr (Laoiseach of the Big Head). Laoiseach Ceann Mr was the one to watch.

Around the year AD 112, the King of Leinster looked for assistance against an invasion from Munster and our man Laoiseach was successful in defeating the Munstermen at Mullaghmast, Coolrus and Magh Riada, and banished them finally at another battle at Mna Droichead near Borris-in-Ossory. As a reward for his brilliant leadership Laoiseach was given Dunamase and its surrounding territories. It is from this man that Laois got its name.

With the Fort at Dunamase as his centre, he divided the area under his control into seven. Better known as the seven tribes of Laois, a portion was given to each of his seven followers.

The OMoores, Lughaidh Laoiseachs own descendants, are likely to have got their name from his big head, his ceann mr . The others were the OKellys, the ODevoys, the ODorans, the OLalors, the ODowlings and the McEvoys. The leaders of these tribes were awarded many privileges at the court of the king, including the right to a sirloin of beef from a cow killed for the kings table. They acted as counsellors and treasurers as well as distributing the kings bounty to bards, musicians and other professionals. Rory OMoore had a hand in setting up the Franciscan monastery in Stradbally and his family is praised in Leabhar na Nua Congbhaile, now known as the Book of Leinster.

Next page