A SALAMANDER IN PERMAFROST?

Without Solzhenitsyn the world would hardly have been the same but does the changing world still need him? As Elisa Krizas book demonstrates, the answer often depends on where and who you are and which part of the authors legacy you prefer to focus on.

In Russia , Solzhenitsyns works defeated the Soviet ban, have (re-)entered the school curriculum and are being staged and televised. His Dictionary of Linguistic Expansion (1990) a quixotic attempt to save underused Russian vocabulary from oblivion has recently gone into a third edition. The Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan , and Russia, in operation since 2010, can be seen as a partial implementation of Solzhenitsyns 1990 manifesto Rebuilding Russia , which advocated fostering ties between Russia, Belarus , and Ukraine ; and suggestively noted the share of Southern Siberia and the Ural Mountains in what Kazakhstan consists of. His film scripts about a Soviet car mechanic ( The Parasite , 1968) and the Kengir uprising ( Tanks Know the Truth , 1959) are perhaps the only substantial pieces that remain unwanted, possibly because of their high production costs.

As far as the West is concerned, with c ommunism in retreat, Solzhenitsyn is no longer a household name as one of the doctrines most iconic detractors and victims. The general decline of the readership in our increasingly visual age is probably affecting Solzhenitsyn more than other authors, because the average length of his books appears prohibitive even to those appreciably intrigued by his controversial (or maybe misunderstood) views on Nazism, homosexuality, Western democracy , and the role of Jews in Russian history (all of which are discussed in Krizas study). Anybody who has read Solzhenitsyns unfinished Red Wheel epic, about World War I and the Russian Revolutions of 1917 in its entirety, in ten volumes, up to 800 pages each may well deserve a monument.

Of Solzhenitsyns relatively shorter fiction, his 1962 novella about Soviet labour camp experience in the early 1950s, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (his arguably best known and most impactful title), is frequently perceived to be of purely historical significance, while his novel Cancer Ward (1967) is likely to gain following among cancer patients and their friends and relatives, given that the number of cancer cases across the globe, now at approximately 14 million annually, is expected to rise twofold over the next two decades. Solzhenitsyns memoirs about his life in the West, The Grain and the Millstones (1998-2003; a sequel to the 1975 USSR-based The Oak and the Calf ), are bound to cause quite a stir when they are translated into English but they have not yet appeared as a separate edition even in Russia, although more than ten years have passed since the last instalment in their serialization (the delay may have been caused by some potentially litigious content).

According to Kriza, Western academia may have a role to play in helping Solzhenitsyn retain some form of public interest beyond Russia, especially if his reception is regularly mediated by recourse to various literary theories (as opposed to judg e ments dictated largely by political stances and affiliations). All in all, it is not easy to speculate if Solzhenitsyns Western reputation as a credible artist-cum-prophet would rebound any time soon, or, to use his own image from the preface to The Gulag Archipelago , his ideas would stay well preserved, like a salamander in permafrost, hoping to impress distant future generations. Meanwhile, in 2012, as a testimony to Solzhenitsyns lasting relevance, the Council of Paris voted (against the objections from the Left) to name a city square in his honour. This may or may not be an encouraging sign.

Andrei Rogatchevski

Professor of Russian Literature and Culture

University of Troms , Norway

Acknowledgements

This book is based on the doctoral research I conducted as a fellow at Aarhus University . First of all, I would like to thank the Faculty of Arts for the generous stipend that made this project possible. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor Karen-Margrethe Simonsen of the Section of Comparative Literature for her valuable advice and her helpful comments on my text. I also thank my co-supervisor Henrik Kaare Nielsen, and the members of my PhD defence committee Svend Erik Larsen, Galin Tihanov, and Anja Tippnerfor their insightful observations on my thesis. I would like to express my gratitude to Andreas Umland, the editor of this series, and ibidem -Verlag for the opportunity to publish in a series I have long been a fan of. I thank Andrei Roga t chevski for his detailed reading of my manuscript and for kindly contributing the foreword of this book. I would also like to thank Victoria Gosling, my proof-reader, for her good work. I am very grateful to my husband, Thomas, for his unwavering support and encouragement (not only) while I worked on this project.

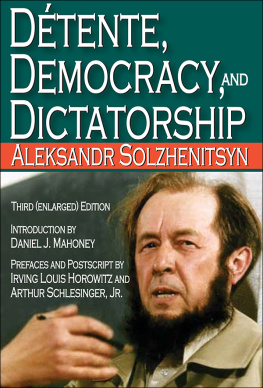

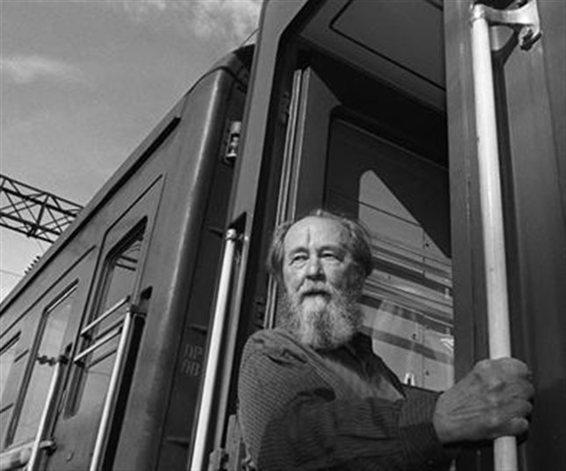

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Russian writer and Nobel prize winner, looks out from a

train, in Vladivostok, summer 1994, before departing on a journey across Russia.

Photo by Mikhail Evstafiev.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

1. Introduction

1.1 The Goal and the Scope of the Study

In this book I analyze the reception of the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn in three Western countries: the US , the UK , and the Federal Republic of Germany. My goal is not a quantitative study of Solzhenitsyns reception in its entirety but a qualitative analysis under specific perspectives. I investigate the role of the historical and political context in Solzhenitsyns reception and its effect on the canonization of his works. Furthermore, I propose new critical readings of his work from a contemporary view point .

T he end of 2013 mark ed exactly forty years since a Russian migr publisher in Paris printed the first edition of Solzhenitsyns T he Gulag Archipelago . The apex of Solzhenitsyns world fame is now a few decades b ehind us . What makes a study of his reception relevant today?

S tudying the reception of this author is relevant both in a particular sense and more general ly . First of all , the results of this study ha ve broader significance because the process of Solzhenitsyns international canonization is associated with his status both as a victim of state violence and as a dissident and this is not unique to the Soviet case . Identifying different canonization mechanisms operating in his reception will give insight into the influence of political, humanitarian , and/or ethical criteria in the assessment of literature under similar circumstances .

Furthermore, Solzhenitsyn is a Nobel Prize winner, and he is an author often described as one of the most significant writers of the 20th century. He has a vast international reception which has received scant attention , making a new and updated study necessary. It is therefore relevant to study the reception of one of the Cold Wars most iconic authors in itself.

Out of the hundreds of dissident writers in Russian history I have chosen to focus on Solzhenitsyn because political dissen t has been more central to his reception than it was in the case of other politically troubled authors, such as Alexander Pushkin, or Joseph Brodsky. In my book , I will explore why this aspect of Solzhenitsyns work is so central, and why his reception seems much more ample than that of similarly politicized writers such as Andrey Sinyavsky.