RESISTANCE IN THE GULAG ARCHIPELAGO (1918-1956)

By Donald G. Boudreau, PhD, MPA

How miserable is a society that knows no better means of defense than an executioner.

-Karl MarxAs quoted by Albert Camus in Camus,

The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt, at 240.

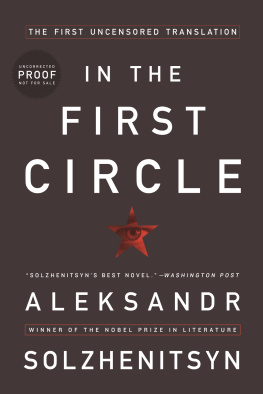

Back in the balmy summer of 1974, I spent many hot and humid nights working as a waiter in a steakhouse restaurant, out on the highway known as US Rt. 22, in northern New Jersey. In arriving home thereafter, late in the evening to a nearby suburb, feeling wired and needing to unwind before sleeping, I began bedtime reading a significant number of works authored by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Solzhenitsyn had been receiving substantial media attention then, regarding his published release a year earlier in 1973 of the first volume of his highly acclaimed The Gulag Archipelago, depicting life and death in the Soviet prison labor camp system during the years 1918-1956.

Given his, Solzhenitsyns firsthand perspective of the harsh life therein the Gulag camps, and reading his lightly fictionalized accounts contained in his many novels and stories and poems authored, I thought it would be useful in exploring the question as to how resistance manifested itself in its many ways among the inmates in the Gulag camps. I set about to doing so through reading the works of Solzhenitsyn and some other observers including noted historians of that particular era, whose writings depicted or otherwise memorialized authoritative experiences, acts of dissenting, protesting, and resisting that had occurred in the Gulag during those years.

In the fall of 1974, while preparing my senior college thesis for the advanced Scope and Methods in Political Science course at Montclair State College (now University) in Upper Montclair, New Jersey, on this very same subject, the senior requirement for a Political Science Major culminated in the student presenting an hour long oral presentation of the same written thesis of some serious length manuscript, before and in front of the entire classroom audience, comprised of the courses professor and ones fellow students.

My dear friend and fellow classmate, Janet Serra, just days before my scheduled senior presentation before the class, kindly presented me with an early surprise birthday present. It was a first edition, hardcover of the just released volume one of Solzhenitsyns The Gulag Archipelago. She was also, admittedly, sparing me in the process she had rightly said, the shamelessly classless embarrassment of having to read excerpts of the same, from my much worn and rabbit eared, paperback edition, during my hour long class presentation that she knew I was to be delivering soon before the entire class.

Thereafter, my professor, the now since retired Dr. George T. Menake, Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Montclair State University, kindly recommended to me in the months thereafter upon returning the graded paper with comments, that he thought I might seriously wish to consider publishing the paper someday, which of course, at the time, I did not do so, that is until this day, as this is largely that same very paper verbatim with some incidental, minor cosmetic changes, which you now have before you.

Although granted, publishing this paper now represents somewhat of a thirty-eight year delay in following up on his, Professor Menakes most thoughtful, prescient suggestion. But while some of the writing here may strike some as a bit dated, given the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union and other related reforms, the topic here presented nonetheless remains valid in our present day, given the worthwhile value in learning more regarding the many ways, creative and otherwise, in which victims historically have gone about resisting tyrannical and totalitarian regimes, worldwide. It is also noteworthy from the standpoint that many observers believe that Russia, the now former Soviet Union, has yet to come to grips with addressing and accepting the truths, the history of Stalin as a leader, and the Stalinist era and that of the Gulag camps, in all of their unvarnished cruelty and horror. See for example, in this regard Fred Hiatt, Russians Seek Rosier Past, Even Revising Stalin Image, [Russians are romanticizing their prerevolutionary era and have even begun to question whether Joseph Stalin and his gulag were as monstrous as perestroika-era revelations suggested.], The Washington Post, October 30, 1994, p. A31, col. 1, bold added. As David Satter (2011) powerfully observes in It Was A Long Time Ago, and It Never Really Happened Anyway: Russia and the Communist Past (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press) the elemental failing of Russias leaders and people is their refusal in facing the moral depravity of its Soviet past, including its most savage manifestation: Joseph Stalins terror.

My appreciation for the accomplishments of Alexander Solzhenitsyn as a gifted writer (he was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature), and as an exhaustively detailed historian of life in Stalinist Russia, has only increased over the several intervening decades. Towards the end of his life, Solzhenitsyn lived in a comfortable compound in nearby Moscow, and was very supportive of organizations providing for the welfare of survivors from the Gulag camps. In supporting their works, Solzhenitsyn was known to make appearances at the Moscow-based offices of such in order to autograph copies of his books; the proceeds of which went to benefiting the victims and their families of those who had, somehow too, survived life in the various Gulag camps, as Solzhenitsyn himself knew well having himself experienced such firsthand.

Fortunately, and thanks to a reputable fine book dealer based in Connecticut who frequented such events in Moscow, I am today the proud owner of the prized possessions of not one, but two rather, beautifully signed copies of Solzhenitsyns The Gulag Archipelago, which I have every intention of bequeathing as invaluable family heirlooms to be treasured and passed on, in turn, by my two beloved children, Katarina and Joseph.

Moreover and finally, given their aforementioned personal contributions made in the fall semester of 1974 to furthering the work of this paper, it is only fitting that I dedicate it here to them both: in ever loving memory of my late beloved dear friend, Janet Serra, for her much valued warm friendship and countless kindnesses. And for his steadfast encouraging support to the much respected scholar, Dr. George T. Menake, Emeritus Professor of Political Science, Department of Political Science and Law, Montclair State University, Upper Montclair, New Jersey, may he have a healthy, long, happy and fruitful retirement. Thank you both sincerely Janet and George, this ones for you two!

Dr. Donald G. Boudreau

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Summer 2012

Here is somewhere to settle forever, a place where a man could live in harmony with the elements and be inspired. But it cannot be. An evil prince, a squint-eyed villain, has claimed the lake for his own: there is his house, there is his bathing place. His evil brood goes fishing here, shoots ducks from his boat. First a wisp of blue smoke above the lake, then a moment later the shot.

Away beyond the woods, the people sweat and heave, whilst all the roads leading here are closed lest they intrude. Fish and game are bred for the villains pleasure. Here there are traces where someone lit a fire but it was put out and he was driven away.

Beloved, deserted lake.

My native land

-Alexander I. Solzhenitsyn (1972)Excerpted in part from Lake Segden, in Solzhenitsyn,

Stories and Prose Poems, at 198-9.

I dedicate this