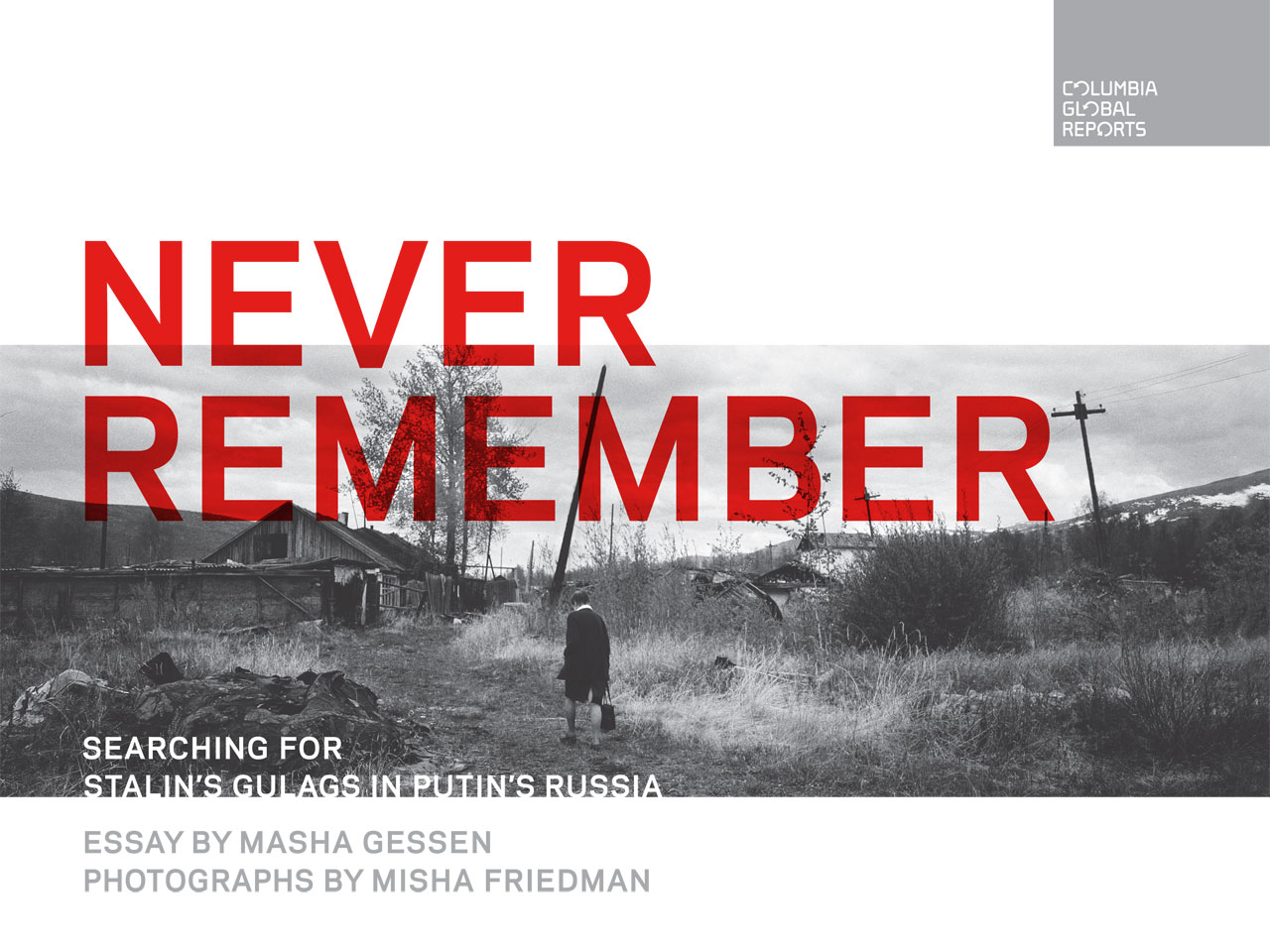

NEVER

REMEMBER

BY MASHA GESSEN AND

MISHA FRIEDMAN

SEARCHING FOR STALINS GULAGS

IN PUTINS RUSSIA

NEW YORK

Never Remember

Searching for Stalins Gulags in Putins Russia

Copyright 2018 by Masha Gessen and Misha Friedman

All rights reserved

Published by Columbia Global Reports

91 Claremont Avenue, Suite 515

New York, NY 10027

globalreports.columbia.edu

facebook.com/columbiaglobalreports

@columbiaGR

Never Remember: Searching for Stalins Gulags in Putins Russia

has been made possible in part by a major grant from the

Wallenberg Executive Committee and the Weiser Center for

Emerging Democracies at the University of Michigan.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016962829

eISBN: 978-0-9977229-7-0

Book design by Strick&Williams

Map design by Jeffrey L. Ward

Author photograph of Masha Gessen Tanya Sazansky

Author photograph of Misha Friedman Sergey Goroshko

Printed in China.

Contents

9

Prologue

Looking for Wallenberg

Chapter One

The Bodies in the Forest

Chapter Two

The Last Daughter

Chapter Three

The Last Camp

Chapter Four

Sergei Kovaliov

Chapter Five

Memory-Building

Chapter Six

Butugychag

Chapter Seven

Inna Gribanova

Chapter Eight

Invisible Memory

Epilogue

The Sculpture Garden

PROLOGUE

Looking for Wallenberg

Of all the men who left and never returned, of all who were remembered and all who were forgotten, of all whose fate never let memory gain a foothold, none might have been sought as desperately or for as long as Raoul Wallenberg. Born in 1912 to a wealthy Swedish family, educated in the United States as an architect, Wallenberg found his calling, in 1944, in Nazi-occupied Hungary. As an envoy of neutral Sweden, Wallenberg used his position to create safehouses for Jews, forge identity documents for Jews, and smuggle Jews out of the country to safety. Most Eastern European Jews had been murdered by then; the turn of the Hungarian Jews came last, when the world was generally aware of the Holocaust. Wallenberg was not the only foreign diplomat in Budapest racing to save Jews; he was not even the one ultimately credited with saving the greatest number of lives. He was the one who disappeared.

Wallenberg vanished after the Red Army entered Hungary. On January 17, 1945, he went to a meeting with Soviet officials and was never again seen by anyone who had known him. After the war Sweden worked to maintain neutrality in a divided Europe. An energetic search for the missing diplomat could have undermined these efforts. Wallenberg was written off.

A decade after Wallenbergs disappearancea decade after the end of the Second World Warthe Soviet Union released surviving German prisoners of war, and they brought memories of Wallenberg. They had heard of himor heard him knocking on cell walls and floors, tapping out messages from solitary confinement in Moscows Lefortovo Prison. Stalin was dead, the new Soviet government was presenting a friendlier face to the West, and Sweden began asking for an accounting. The United States, worried about

MASHA GESSEN AND MISHA FRIEDMAN

COLUMBIA GLOBAL REPORTS

the newly seductive Soviet posture, did what it could to arouse interest in Wallenberg among the Swedish mediaas a public-opinion hedge against coziness with the USSR. Moscow finally produced a handwritten document indicating that Wallenberg had died of a heart attack in Soviet custody on July 17, 1947.

It was Alexander Solzhenitsyn who rekindled the search for Wallenberg nearly twenty years later. In Stockholm to collect his Nobel Prize for literaturefour years after it was awarded in 1970, before he was exiled from the Soviet Unionthe man who had memorialized the Gulag by putting a myriad voices on paper told Wallenbergs parents that their son could still be alive. Over the next fifteen years, the urgency of the search continued to intensify.

There were rumors. One had it that a character in The Gulag Archipelago, an apparition among inmates who wears his hair long and is transported in a separate compartment, who says that he is a Swede from a wealthy family named Anderson, was in fact Wallenberg. He was not. But he could have been. Anything was possible in the absence of knowledge. If Anderson had been Wallenberg, that would have meant that Wallenberg was still alive in the 1950s.

There were witnesses. They claimed that they had seen Wallenberg in a jail, in a camp, in a prison infirmary, in a mental hospital, in Moscow, in central Russia, in Siberia, in the Far East, in the 1950s, the 1970s, and even the 1980s. All of them were lying. Whether these liars were seeking attention, money, or nothing at all, their falsifications landed in fertile soil. Wallenbergs family longed to believe that he was alive, and the CIA kept tending to the story, to ensure that Sweden did not forget the Soviet crime against it.

Thirty-five years after his disappearance, Raoul Wallenberg began gathering international recognition. There were books,

films, monuments, streets, and squares, in New York City, Washington, and Stockholm. There were honorary citizenships: American, Canadian, and Israeli. The idea that the man being honored might still be aliveWallenberg would have been in his seventies in the 1980sgave this growing international movement its energy and an edge of desperation. The idea that he might have died in a Soviet prison camp during the decades of relative silence gave it an edge of shame. I first learned of Wallenberg from an article my mother wrote for a Russian-language emigre newspaper in New York. She wrote that Wallenberg was a man who tried to save the world whom the world failed to save.

Perestroika began in 1985. The policy of glasnostopenness started loosening information from KGB archives. Organizations that called themselves Memorial Societies began forming in cities and towns all over the USSR, for the purpose of excavating the memory of the Gulag. Soviet citizens started asking what had happened to members of their families, and getting some answers.

Wallenbergs siblings traveled to Moscow in October 1989 (his parents had died) and had an audience with a top secret-police official. It turned out that the points of departure for the conversation diverged strongly, one of Wallenbergs biographers later wrote. The siblings had come in order to free their brother. The KGB general had been assigned the task of once and for all convincing the family that Wallenberg was dead. Both sides failed.

Next page