ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No book is ever really the work of one person, but this book truly could not have been written without the practical, intellectual, and philosophical contribution of many people, some of whom count among my closest friends, and some of whom I never met. Although it is unusual, in acknowledgments, for authors to thank writers who are long dead, I would like to give special recognition to a small but unique group of camp survivors whose memoirs I read over and over again while writing this book. Although many survivors wrote profoundly and eloquently of their experiences, it is simply no accident that this book contains a preponderance of quotations from the works of Varlam Shalamov, Isaak Filshtinsky, Gustav Herling, Evgeniya Ginzburg, Lev Razgon, Janusz Bardach, Olga Adamova-Sliozberg, Anatoly Zhigulin, Alexander Dolgun, and, of course, Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Some of these number among the most famous of Gulag survivors. Others do notbut they all have one thing in common. Out of the many hundreds of memoirs I read, theirs stood out, not only for the strength of their prose but also for their ability to probe beneath the surface of everyday horror and to discover deeper truths about the human condition.

I am also more than grateful for the help of a number of Muscovites who guided me through archives, introduced me to survivors, and provided their own interpretations of their past at the same time. First among them is the archivist and historian Alexander Kokurinwhom I hope will one day be remembered as a pioneer of the new Russian historyas well as Galya Vinogradova and Alla Boryna, both of whom dedicated themselves to this project with unusual fervor. At different times, I was aided by conversations with Anna Grishina, Boris Belikin, Nikita Petrov, Susanna Pechora, Alexander Guryanov, Arseny Roginsky, and Natasha Malykhina of Moscow Memorial; Simeon Vilensky of Vozvrashchenie; as well as Oleg Khlevnyuk, Zoya Eroshok, Professor Natalya Lebedeva, Lyuba Vinogradova, and Stanisaw Gregorowicz, formerly of the Polish Embassy in Moscow. I am also extremely grateful to the many people who granted me long, formal interviews, whose names are listed separately in the Bibliography.

Outside of Moscow, I owe a great deal to many people who were willing to drop everything and suddenly devote large chunks of time to a foreigner who had arrived, sometimes out of the blue, to ask nave questions about subjects they had been researching for years. Among them were Nikolai Morozov and Mikhail Rogachev in Syktyvkar; Zhenya Khaidarova and Lyuba Petrovna in Vorkuta; Irina Shabulina and Tatyana Fokina in Solovki; Galina Dudina in Arkhangelsk; Vasily Makurov, Anatoly Tsigankov and Yuri Dmitriev in Petrozavodsk; Viktor Shmirov in Perm; Leonid Trus in Novosibirsk; Svetlana Doinisena, director of the local history museum in Iskitim; Veniamin Ioffe and Irina Reznikova of St. Petersburg Memorial. I am particularly grateful to the librarians of the Arkhangelsk Kraevedcheskaya Biblioteka, several of whom devoted an entire day to me and my efforts to understand the history of their region, simply because they felt it was important to do so.

In Warsaw I was greatly aided by the library and archives run by the Karta Institute, as well as by conversations with Anna Dzienkiewicz and Dorota Pazio. In Washington, D.C., David Nordlander and Harry Leich helped me at the Library of Congress. I am particularly grateful to Elena Danielson, Thomas Henrikson, Lora Soroka, and especially Robert Conquest of the Hoover Institution. The Italian historian Marta Craveri contributed a great deal to my understanding of the camp rebellions. Conservations with Vladimir Bukovsky and Alexander Yakovlev also helped my comprehension of the post-Stalinist era.

I owe a special debt to the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the John M. Olin Foundation, the Hoover Institution, the Mrit and Hans Rausing Foundation, and John Blundell at the Institute of Economic Affairs for their financial and moral support.

I would also like to thank the friends and colleagues who offered their advice, practical and historical, during the writing of this book. Among them are Antony Beevor, Colin Thubron, Stefan and Danuta Waydenfeld, Yuri Morakov, Paul Hofheinz, Amity Shlaes, David Nordlander, Simon Heffer, Chris Joyce, Alessandro Missir, Terry Martin, Alexander Gribanov, Piotr Paszkowski, and Orlando Figes, as well as Radek Sikorski, whose ministerial briefcase proved very useful indeed. Special thanks are owed to Georges Borchardt, Kristine Puopolo, Gerry Howard, and Stuart Proffitt, who oversaw this book to completion.

Finally, for their friendship, their wise suggestions, their hospitality, and their food I would like to thank Christian and Natasha Caryl, Edward Lucas, Yuri Senokossov, and Lena Nemirovskaya, my wonderful Moscow hosts.

Also by Anne Applebaum

Between East and West:

Across the Borderlands of Europe

Appendix

HOW MANY?

ALTHOUGH THE SOVIET UNION contained thousands of concentration camps, and although millions of people passed through them, for many decades the precise tally of victims was concealed from all but a handful of bureaucrats. As a result, estimating their numbers was a matter of sheer guesswork while the USSR existed, and remains a matter of educated guesswork today.

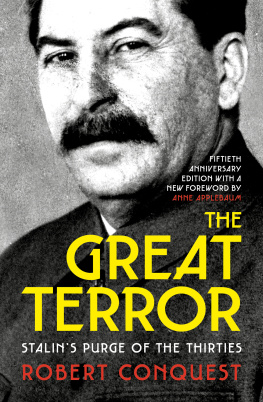

During the era of sheer guesswork, the Western debate about the statistics of repressionjust like the more general Western debate about Soviet historywas tainted, from the 1950s on, by the politics of the Cold War. Without archives, historians relied alternately on prisoners memoirs, defectors statements, official census figures, economic statistics, or even minor details which somehow became known abroad, such as the number of newspapers distributed to prisoners in 1931.1 Those more inclined to dislike the Soviet Union tended to choose the higher figures of victims. Those more inclined to dislike the American or Western role in the Cold War chose the lower figures. The numbers themselves ranged wildly. In The Great Terror , his then groundbreaking 1968 account of the purges, the historian Robert Conquest esimated that the NKVD had arrested seven million people in 1937 and 1938.2 In his 1985 revisionist account, Origins of the Purges, the historian J. Arch Getty wrote of merely thousands of arrests in those same two years.3

As it turned out, the opening of the Soviet archives gave neither school complete satisfaction. The first sets of figures released for Gulag prisoners seemed at first to show numbers lying squarely in the middle of the high and low estimates. According to widely published NKVD documents, these were the numbers of prisoners in Gulag camps and colonies from 1930 to 1953, as counted on January 1 of each year:

These numbers do reflect some things that we know, from many other sources, to be true. The inmate figures begin to rise in the late 1930s, as repression increased. They dip slightly during the war, reflecting the large numbers of amnesties. They rise in 1948, when Stalin clamped down once again. On top of all that, most scholars who have worked in the archives now agree that the figures are based on genuine compiliations of data provided to the NKVD by the camps. They are consistent with data from other parts of the Soviet government bureaucracy, tallying, for example, with data used by the Peoples Commissariat of Finance.5 Nevertheless, they do not necessarily reflect the whole truth.

To begin with, the figures for each individual year are misleading, since they mask the camp systems remarkably high turnover. In 1943, for example, 2,421,000 prisoners are recorded as having passed through the Gulag system, although the totals at the beginning and end of that year show a decline from 1.5 to 1.2 million. That number includes transfers within the system, but still indicates an enormous level of prisoner movement not reflected in the overall figures.6 By the same token, nearly a million prisoners left the camps during the war to join the Red Army, a fact which is barely reflected in the overall statistics, since so many prisoners arrived during the war years too. Another example: in 1947, 1,490,959 inmates entered the camps, and 1,012,967 left, an enormous turnover which is not reflected in the table either.7

Next page