Anne Applebaum - Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine

Here you can read online Anne Applebaum - Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Penguin, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

RED FAMINE

Stalins War on Ukraine

Contents

ep TB a

To the victims

List of Illustrations

. Ukrainian Declaration of Independence, 9 January 1918. . Cover of Nashe Mynule , 1918, by Heorhiy Narbut. . Independence rally in Kyiv, 1917. . Mykhailo Hrushevsky. . Cover of Hrushevskys History of Ukraine (1917). . Symon Petliura and Jzef Pisudski, Stanyslaviv, 1920. . Nestor Makhno. . Pavlo Skoropadsky. . Oleksandr Shumskyi. . Mykola Skrypnyk. . Grigorii Petrovskii. . Vsevelod Balytsky. . Auction of kulak property. . Kulak family on their way to exile. . Confiscating icons, Kharkiv. . Discarded churchbells, Zhytomyr. . Peasants besides the ruins of a burned house. . Women vote to join a collective farm. . Peasants listening to the radio. . Peasant family reading Pravda. . Harvesting tomatoes. . Volunteers bringing in the harvest.. Searchers find grain hidden from requisitions.

. Guarding fields. . Guarding grain stores. . Peasants leaving home in search of food. . An abandoned peasant house. . People starving by the side of the road. . A starving family. . Peasant girl.. Breadlines in Kharkiv.

. Famine in Kharkiv, spring 1933.

. A starving man, alive and then dead.

. A family in Chernihiv, before and after the famine.

. Famine Rules Russia, Gareth Jones, Evening Standard , 31 March 1933. . Walter Duranty dining in Moscow. . Russians Hungry but not Starving, Walter Duranty, The New York Times , 31 March 1933. . Lazar Kaganovich, Joseph Stalin, Pavlo Postyshev and Klement Voroshilov, 1934. . Mass grave outside Kharkiv, 1933.List of Maps

A Note on Transliteration

The transliteration of Ukrainian names and place names in this book follows the standard set out by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. The Library of Congress transliteration rules for Ukrainian names and place names are followed strictly in the endnotes; in the text, names and place names are written without primes, since that seems more familiar to an English reader. Russian and Belarusian place names are transliterated according to the rules of those languages. A few well-known names and place names, including Moscow and Odessa, have been left in their better-known forms, also to make them recognizable to English-language readers.

Preface

The warning signs were ample. By the early spring of 1932, the peasants of Ukraine were beginning to starve. Secret police reports and letters from the grain-growing districts all across the Soviet Union the North Caucasus, the Volga region, western Siberia spoke of children swollen with hunger; of families eating grass and acorns; of peasants fleeing their homes in search of food. In March a medical commission found corpses lying on the street in a village near Odessa. No one was strong enough to bury them. In another village local authorities were trying to conceal the mortality from outsiders. They denied what was happening, even as it was unfolding before their visitors eyes.

Some wrote directly to the Kremlin, asking for an explanation:

Honourable Comrade Stalin, is there a Soviet government law stating that villagers should go hungry? Because we, collective farm workers, have not had a slice of bread in our farm since January 1 How can we build a socialist peoples economy when we are condemned to starving to death, as the harvest is still four months away? What did we die for on the battlefronts? To go hungry, to see our children die in pangs of hunger?Others found it impossible to believe the Soviet state could be responsible:

Every day, ten to twenty families die from famine in the villages, children run off and railway stations are overflowing with fleeing villagers. There are no horses or livestock left in the countryside The bourgeoisie has created a genuine famine here, part of the capitalist plan to set the entire peasant class against the Soviet government.But the bourgeoisie had not created the famine. The Soviet Unions disastrous decision to force peasants to give up their land and join collective farms; the eviction of kulaks, the wealthier peasants, from their homes; the chaos that followed; these policies, all ultimately the responsibility of Joseph Stalin, the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, had led the countryside to the brink of starvation. Throughout the spring and summer of 1932, many of Stalins colleagues sent him urgent messages from all around the USSR, describing the crisis. Communist Party leaders in Ukraine were especially desperate, and several wrote him long letters, begging him for help.

Many of them believed, in the late summer of 1932, that a greater tragedy could still be avoided. The regime could have asked for international assistance, as it had during a previous famine in 1921. It could have halted grain exports, or stopped the punishing grain requisitions altogether. It could have offered aid to peasants in starving regions and to a degree it did, but not nearly enough.

Instead, in the autumn of 1932, the Soviet Politburo, the elite leadership of the Soviet Communist Party, took a series of decisions that widened and deepened the famine in the Ukrainian countryside and at the same time prevented peasants from leaving the republic in search of food. At the height of the crisis, organized teams of policemen and party activists, motivated by hunger, fear and a decade of hateful and conspiratorial rhetoric, entered peasant households and took everything edible: potatoes, beets, squash, beans, peas, anything in the oven and anything in the cupboard, farm animals and pets.

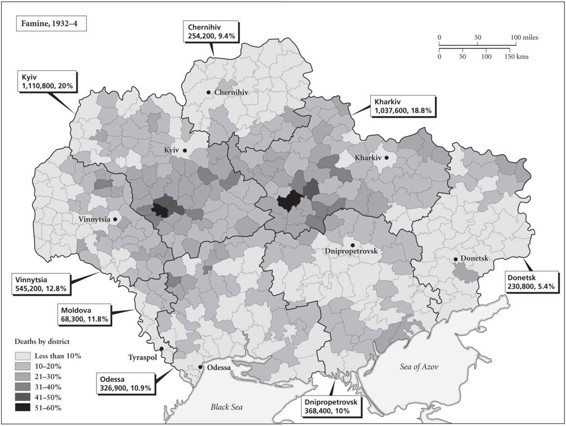

The result was a catastrophe: At least 5 million people perished of hunger between 1931 and 1934 all across the Soviet Union. Among them were more than 3.9 million Ukrainians. In acknowledgement of its scale, the famine of 19323 was described in migr publications at the time and later as the Holodomor , a term derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger holod and extermination mor .

But famine was only half the story. While peasants were dying in the countryside, the Soviet secret police simultaneously launched an attack on the Ukrainian intellectual and political elites. As the famine spread, a campaign of slander and repression was launched against Ukrainian intellectuals, professors, museum curators, writers, artists, priests, theologians, public officials and bureaucrats. Anyone connected to the short-lived Ukrainian Peoples Republic, which had existed for a few months from June 1917, anyone who had promoted the Ukrainian language or Ukrainian history, anyone with an independent literary or artistic career, was liable to be publicly vilified, jailed, sent to a labour camp or executed. Unable to watch what was happening, Mykola Skrypnyk, one of the best-known leaders of the Ukrainian Communist Party, committed suicide in 1933. He was not alone.

Taken together, these two policies the Holodomor in the winter and spring of 1933 and the repression of the Ukrainian intellectual and political class in the months that followed brought about the Sovietization of Ukraine, the destruction of the Ukrainian national idea, and the neutering of any Ukrainian challenge to Soviet unity. Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish lawyer who invented the word genocide, spoke of Ukraine in this era as the classic example of his concept: It is a case of genocide, of destruction, not of individuals only, but of a culture and a nation. Since Lemkin first coined the term, genocide has come to be used in a narrower, more legalistic way. It has also become a controversial touchstone, a concept used by both Russians and Ukrainians, as well as by different groups within Ukraine, to make political arguments. For that reason, a separate discussion of the Holodomor as a genocide as well as Lemkins Ukrainian connections and influences forms part of the epilogue to this book.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine»

Look at similar books to Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.