Anne and I are unlikely cookbook writers. She is an acclaimed, prize-winning historian and columnist who has spent most of her career covering the politics of Eastern Europe and Russia. Im a Washington-based journalist, editor, and author who has mostly occupied herself with politics and womens issues. And many people would suggest that Polish food is an unlikely topic for a cookbook. We encountered this reaction throughout the writing of our book:

What are you working on now?

A Polish cookbook.

Snickers or a perplexed look. Then, unfailingly, a reply along the following lines:

How many recipes can you get out of boiled potatoes?

Unfortunately for many of us, including the millions of North Americans with Polish ancestry, the very term Polish cooking conjures up memories of heavy, greasy dishes: the food of exile and poverty. And as Anne notes in her introduction, the reputation of Polish cooking was not enhanced by forty-five years of communism. But what youll find in the following pages is not, as one might say, your grandmothers cooking.

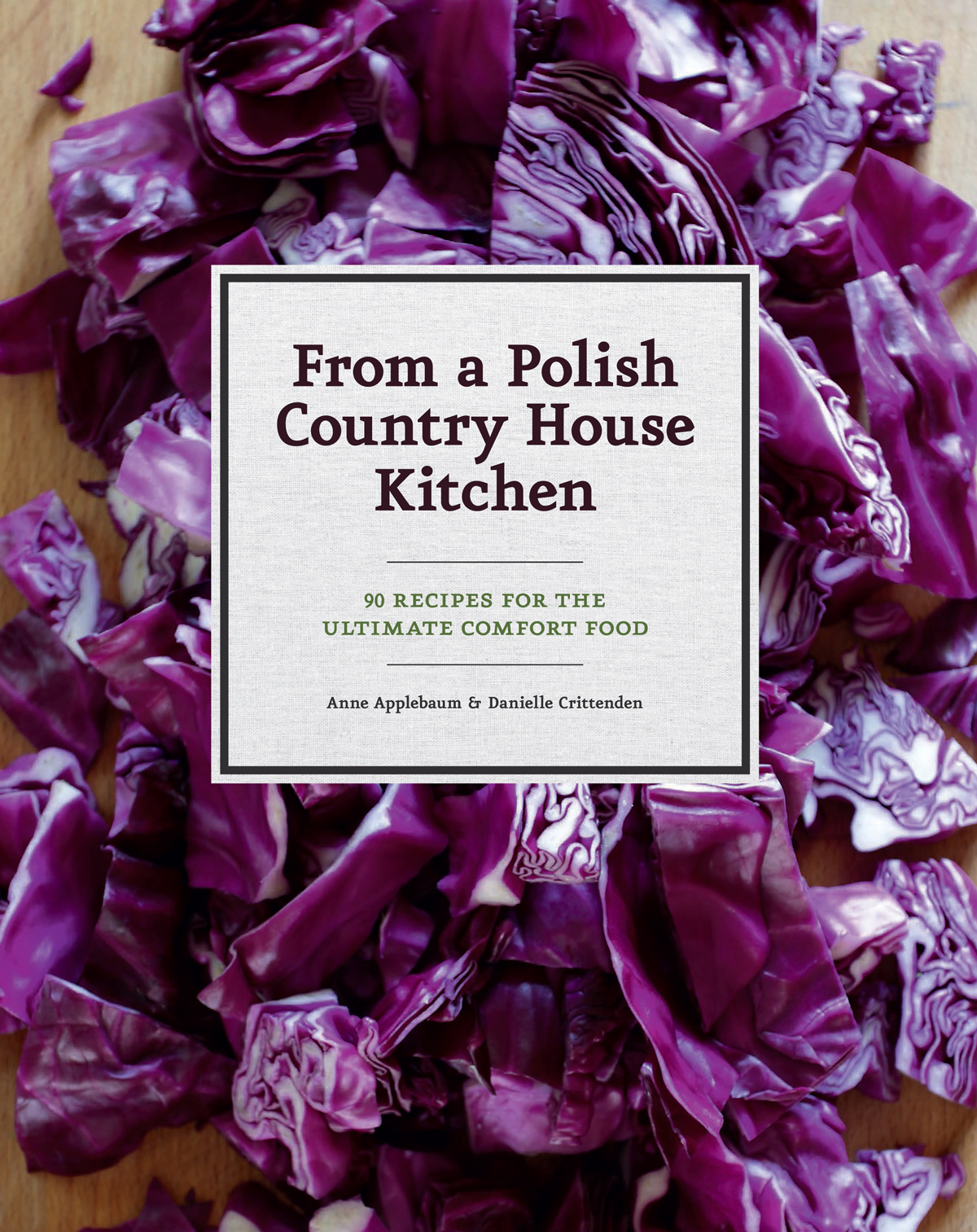

Anne and I conceived this book a few summers ago on the back porch of her beautiful Polish country house, Dwor Chobielin. (Dwor means manor.) Anne and her husband, Radek Sikorski (at that time Polands defense minister), had invited a group of their American friends to come stay with them. Few of us had ever been to Poland, and none of us had yet visited the house that Anne and Radek had purchased for next to nothing right after communism fell in 1989. The couple had devoted two decades to rebuilding the ruined nineteenthcentury pile near Bydgoszcz, quite literally from the ground up.

Radek and Anne led us on a leisurely bike ride through tall forests and winding side roads. We ate a picnic in the shadow of a lovely restored church. We stopped for ice cream in the main square of the nearby village of Nako. Later, in lazy repose on their pillared back porch, wine glasses in hand, we admired the sweeping clipped lawn, which was bordered by rows of fruit trees. An impressive vegetable garden, with greenhouse, had been laid out near their picturesque old barn. Anne stepped out with a basket to collect the lush plums and soft lettuces that would later reappear at dinner.

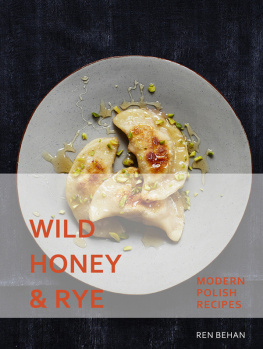

At that moment we all had to concede that our preconceived notions of everything wed see and eat in Poland were utterly and completely shattered. Our group had arrived in Warsaw a few days previously, and wed taken some time to tour the magically rebuilt old city and other historical sites. Then wed driven three hours to Chobielin, pausing to stop for lunch in the spectacular medieval village of Toru (birthplace of Copernicus). The culinary renaissance we encountered everywhere thrillingly symbolizedas much as the new highways or glittering glass skyscrapersPolands national rebirth. The pierogi, or potato dumplings, that you can buy from supermarket freezers in North America, in no way resembled the delicate dumplings we were served in even the most modest of restaurant kitchens. These pierogi werent doughy or oily or overstuffed with bland cheese. As delicate and translucent as Hong Kongs finest dim sum, they contained all sorts of original fillings. (My favorites were the ones that burst with the intensity of freshly picked wild mushrooms with an ever so slightly sour hint of sauerkraut.)

Beet soupor what we so often associate with dishwatery thin and flavorless borschtarrived as pink and silky as a sunset, occasionally with the exotic surprise of a bright yellow quails egg yolk sinking into light streaks of sour cream. And then there was our introduction to game, meats that some lucky rural Polesthose who hunt or have friends who huntkeep in their freezers the same way North Americans keep chicken, beef, and pork. For us, they opened up a whole new palate.

On this trip, too, Anne and I discovered that we shared a passion for cookingand especially cooking for company. Given the political circles we both travel in, there are lots of occasions for it. I think neither of us can imagine a more pleasurable evening than sitting down to dinner with a mix of fascinating guests, whose lively conversation is fueled by home-cooked food that is hearty, unpretentious, and, above all, delicious.

Anne and I also discovered that we both shared a love of cooking with fresh, seasonal ingredients. At Chobielin and across Poland there still exists a culture that has all but vanished in the rich, sterile produce aisles of Western supermarkets, one that is only slowly being rediscovered in the growing prevalence of local farmers markets. I noticed that even the most urbanized Poles still knew how to string and dry mushrooms, pickle cucumbers, and make jam. These skills may have been enforced by decades of economic hardship, as Anne describes in her introduction, but they deliver pure joy: Even a poor Polish farmer who pulls his own potato from the ground will experience something far tastier than the wealthy Western European who plucks his potato from the mass-produced selections stacked in pyramids at his grocery store. Anyone who has ever grown something as simple as a cherry tomato on her city patio knows that her sweet and juicy little crop in no way resembles the waxy red marbles the supermarkets sell in January. A carrot pulled fresh from the dirt, a young sugary beet with its crisp veined leaves, a velvety green bean picked right off its vinethese are what we tasted from Annes own garden, and they tasted like nothing Id had before. Her example inspired me to seek out such freshness when I returned back home to DC; since then Ive been growing small crops of lettuces in my backyard, and enjoying the seasonal produce that has become increasingly more available from nearby Virginia and Maryland farms.