In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

Copyright 2013 by William Sitwell

Cover 2013 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Pig illustration Neil Gower

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: June 2013

A version of this book was previously published in the UK by Collins, copyright by William Sitwell, 2012.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN: 978-0-316-25570-7

For Laura

W illiam Sitwell is the editor of Waitrose Kitchen magazine, can regularly be seen on TV programs such as BBC2s Food & Drink and MasterChef: The Professionals, and writes about food for a variety of newspapers and magazines. Following an early career in newspapers, he came to prominence in the food world after 1999 when he joined the then titled Waitrose Food Illustrated, of which he became editor in 2002. He subsequently won a string of awards, including Editor of the Year in 2005, for the magazines writing, stories, design and photography. He spends his spare time growing vegetables, cooking, and making cider at his home in Northamptonshire, England, where he lives with his wife, Laura, and their children, Alice and Albert. This is his first book.

Simon Brown

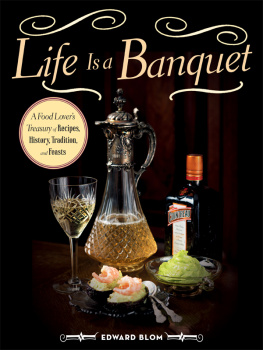

A fter an auction at Sothebys, London, in the summer of July 2010, I came away with an armful of nineteenth-century cookery books and a smattering of food-related paintings and cartoons. They had been a tiny part of a vast culinary collection owned by one Stanley J. Steeger, a collector from New York. Now, as I took them to my home in the English countryside, they would be a large part of a rather small collection of one William R. S. Sitwell.

There on a shelf in my study, a room filled with giant photographs of foodripened figs in a bowl, peas in a pod and a Damien Hirststyle shark in jellythe books added intellectual and historical weight to what I already had. There were cookery books sent to me by publishers and PRs over the years hoping for coverage in the food magazine I edit, autobiographies penned by famous chefs I know and the odd food tome that I had actually paid for.

I started leafing through the old books I had bought, slightly wondering if, while they certainly gave character to the shelf, they would be as dry to read as they looked from their tired bindings and browned paper. But I was quickly struck by the characterful writing that leapt from so many of the pages. Where I had expected placid cooking instruction I found verbose opinion. Entries in the nineteenth-century Cassells Dictionary of Cookery, for instance, were filled with radical opinion and comment. It is a shocking thought that many die annually of absolute starvation, whose lives might have been saved twenty times over, wrote the editor, A. G. Payne, in a long and ranting introduction.

That view sounded rather familiar, I thought. Scraps of meat, fag ends of pieces of bacon, too often wasted, with a little judicious management, make a nice dish of rissoles, it continued, making the idea that using leftovers was fashionableas promulgated in magazines such as mineseem laughably prosaic.

I came across the writings of Dr. William Kitchiner in his hilarious 1817 Cooks Oracle, in which, aside from describing in every gory detail some of the cruelest cooking practices he had ever heard of (dont worryIve also conveyed it with no stone left unturned, see cuisine of the Paris Jockey Clubin whose Royal Cookery Book of 1868 he attacked the perfect uselessness of such cookery books as have hitherto been published.

This all sounded very familiar. Didnt every PR sending me a new cookbook from the latest culinary sensation claim that there hadnt been one quite like this one, that no previous book had been written with such clarity, that the recipes in this book really worked, that it was a new style of cooking guaranteed to capture the publics imagination?

Deciding to delve a little deeper, I soon came across Hannah Glasse, who had published The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy in 1747. It could have been 2011. Her book, she declared, far exceeds anything of the kind ever yet published. I believe I have attempted a brand of cookery which nobody has yet thought worth their while to write upon.

Then back in 1500 there was This Boke of Cokery in which the anonymous author stated: Here begynneth a noble boke of festes ryalle and cookery a boke for a princes household or any other estates and the makynge therof according as ye shall find more playnely with this boke. The inference is clear: this boke was plainer, simpler and clearer than any other boke.

As well as such bold claims of authenticity and brilliance, it struck me that across the centuries the characters making these claims were as strong as the sentiments they expressed. In other words, there is nothing new about chefs today being mad, bad, passionate, obsessive foodie fanatics. Furious rages echo out of kitchens throughout history, as does a passion for the best ingredients. Just as in the late 1980s Marco Pierre White was throwing the contents of a badly arranged cheese board at the wall of his restaurant, back in 350 BC the Sicilian Archestratus was losing his rag. If you wanted good honey, he said, it was only worth getting the stuff from Attica, otherwise you might as well be buried measureless fathoms underground. And if you didnt cook simply and poured sauce over everything, you might as well be preparing a tasty dish of dogfish.

Just as the passions of chefs, producers and consumers of food have brought the subject of food alive for me over the years, so this book is an investigation into, and a tribute to, the passionate people who have driven its story forward over the centuries. Were it not for a few rampant gourmands like the sauce-loving Apicius who in AD 10 wrote the only surviving cookbook from ancient Rome, or cheese-obsessed Pantaleone da Confienza sniffing his way around the dairies of Europe in the mid-fifteenth century, the dim and distant past would be a great deal dimmer and considerably less tasty.

Next page