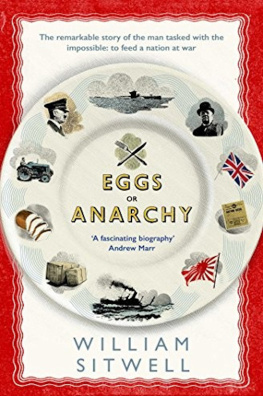

EGGS OR

ANARCHY

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2016

A CBS COMPANY

Copyright 2016 by William Sitwell

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of William Sitwell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

The author and publishers have made all reasonable efforts to contact copyright-holders for permission, and apologise for any omissions or errors in the form of credits given. Corrections may be made to future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-4711-5105-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-4711-5108-8

Typeset in the UK by M Rules

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd are committed to sourcing paper that is made from wood grown in sustainable forests and support the Forest Stewardship Council, the leading international forest certification organisation. Our books displaying the FSC logo are printed on FSC certified paper

For Alice and Albert

A UTHOR S N OTE

The quotes from Lord Woolton and other main protagonists such as his wife Maud Woolton or Winston Churchill are mainly based on Wooltons own writings, from his memoirs, diaries, a long tribute he wrote to his late wife, from his letters and other personal writings and also the diaries of his wife Maud. While his memoirs are more tempered, his private writings are quite extraordinary in both style, tone, temper and sound. So most quotes, dialogue and speech come from those writings often using multiple sources for individual scenes which would make the constant referencing of them tiresome. If I have ever paraphrased, elongated or massaged a quote, it is done faithfully and with respect for both the original source material and the reader.

1

A N EW M AN AT THE M INISTRY

Late afternoon, Thursday 3 April 1940. Seven months into the Second World War and, in an office in Londons Tothill Street in Westminster, a grey-haired man in his late fifties, dressed in a three-piece pin-striped suit, with a watch chain, was placing the few remaining items left on his desk a small framed picture and an ink pot into a box. In an ashtray a pipe smouldered.

Fred Marquis, latterly ennobled as Lord Woolton, was leaving his post, an advisory position with the less-than-exciting title of Director General of Equipment and Stores. His new role had a simpler name and was a touch more glamorous: in a matter of hours he would be Minister of Food.

The previous day, Woolton had received a telephone call from the Prime Ministers office, asking if he would visit Neville Chamberlain at seven oclock that evening.

I understand that your department is running so smoothly that you are now unnecessary, were Chamberlains opening words when they met.

Woolton, in his memoirs, wrote that it was said without a smile, in his rather cold manner, and I realized that for some reason or other he proposed to remove me.

Woolton assumed that he would then be released to return to his actual day job, as head of the Manchester-based (and countrys biggest) department store chain, Lewiss.

Am I now free to go and look after my own business affairs? asked Woolton.

Chamberlain replied that this was not his intention, instead he was making some changes in his Cabinet and he wanted Woolton to join the government as Minister of Food.

The task would see Woolton heading a ministry whose job was, in simple terms, to feed Britain and her colonies during the straitened times of the Second World War.

That meant 41 million men, women and children in Britain and Northern Ireland, with an oversight of the 532 million people of the British Empire. He would have to manage the purchase and importation of food, ensure its fair distribution across the country, tackle the very low productivity of home-grown sustenance, and, with the system of rationing that had begun on 8 January of that year, ensure that abuses of the system were kept to a minimum and a black market thwarted.

Woolton left Downing Street, discussed the proposal with his wife Maud and then accepted the job the following day. At which point he immediately began to feel apprehensive.

I was embarking on a new life, he later reflected, at the age of fifty-eight, with many fears about my own capacity to succeed in these new and unaccustomed fields of parliamentary responsibility, and with a profound sense of the dire consequences to the country if I failed.

As he cleared his office he considered the challenges of the coming days. His new offices were just north of Oxford Street, physically some two miles away from the political machine of government in Whitehall.

He would get his feet under the desk and spend the days and nights reading to get on top of the subject. There was a large bureaucracy that supported the ministry and he wondered how immovable a beast it would be.

He pondered on the day he would be presented to the press as the new minister and vowed to be ready for the difficult questions that would be thrown his way.

Those first few days of reading and research would be invaluable; he was a stickler for detail and accuracy. He was also a man of firm mind and steely determination, and remained resolute that no decision, no public comment should ever be made without a very clear understanding of the facts.

There was a knock at the door and the secretary who had served him well since he had taken up his post at the Ministry of Supply just days after war had been declared announced a visitor.

Sir Henry French is here for you, Lord Woolton, the secretary said.

Woolton looked startled. He had heard about this man; a career civil servant, Sir Henry French was the Ministry of Foods Permanent Secretary, classically implacable and solemn. Sir Henry had joined the Civil Service in 1901 at the age of eighteen as a second-division clerk to the Board of Agriculture; moving slowly but steadily up the ranks, he had built a reputation as a sound, if inflexible, administrator until joining the Ministry of Food at the start of the war. Fifty-six when war broke out, Sir Henry had spent thirty-eight of those years in the same department. He was, according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, unapproachable and vain. He made up his mind about people and rarely changed it. He was known to wear the responsibilities of his job in the lines on his face, and there was no known evidence that he had a sense of humour.

Woolton wondered how they would get on. He was a man who liked to get things done, who would often circumvent the traditional channels to implement decisions. Since starting work for the government some six months previously, his battles with the Civil Service had already landed him in hot water. He was keen to start this new job on the front foot. He would be ready for Sir Henry French.

He would settle into his new office, take a puff on his pipe, having spent time studying the machinations of his new ministry. Then he would call upon his Permanent Secretary.

Next page