THE WARTIME GARDEN

Twigs Way

Detail from image on .

With part of the flower borders being taken up by vegetables, any decorative plants were often crammed into small spaces.

CONTENTS

Providing for the Home Front, the wartime garden played an essential role in victory.

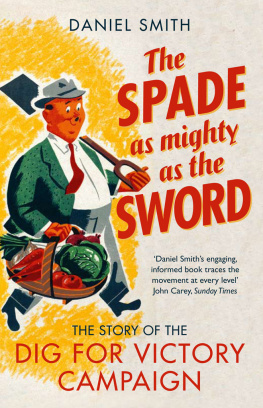

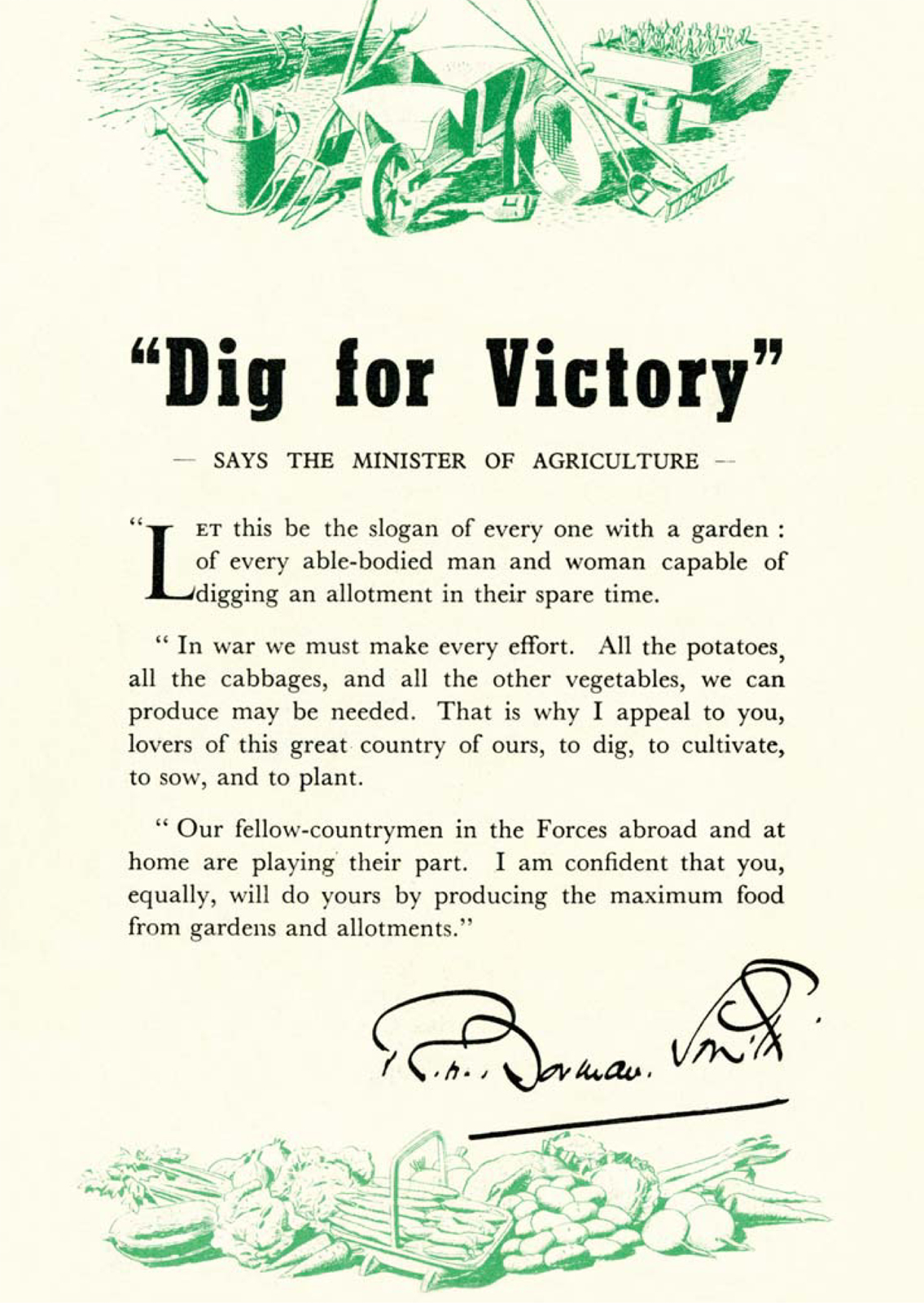

INTRODUCTION: THIS IS A FOOD WAR

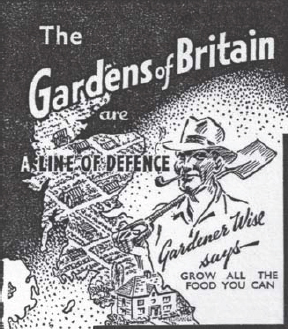

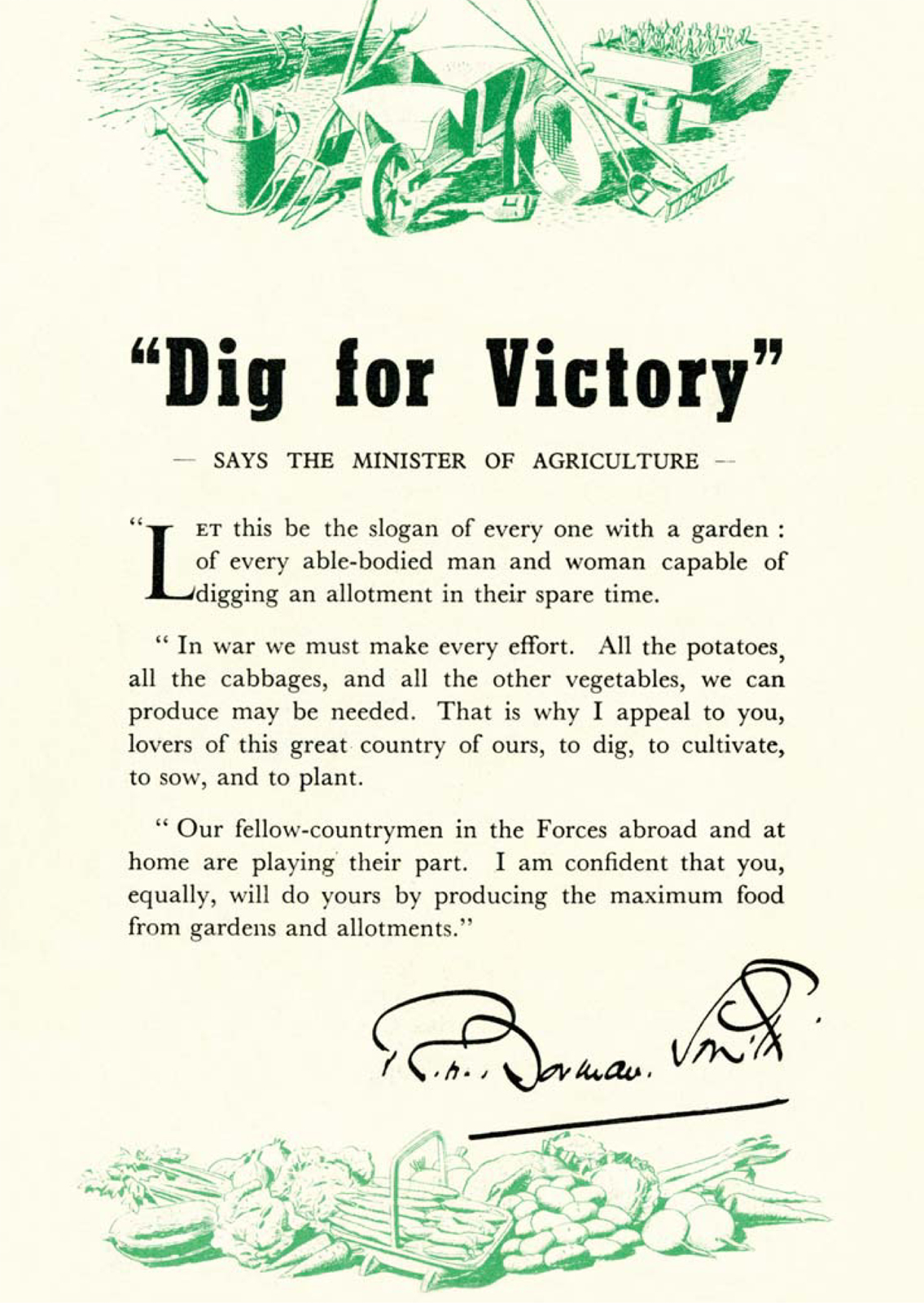

I NSPIRING OVER 1.5 million allotments, 10 million leaflets and thousands of Victory Garden fetes, Dig for Victory was one of the most memorable and successful campaigns of the Second World War. The campaign defined the wartime garden: turning lawns into vegetable plots, flower borders to lettuce beds, and decorating Anderson air-raid shelters with marrows. Between the autumn of 1939 and the summer of 1945 the government variously enticed, cajoled and threatened the nation to take up forks and spades and do their bit on the Garden Front. The gardens of Britain were its Line of Defence. It was a line that looked to women and children, as well as to men, for support: bringing together town and country, rich and poor, to feed wartime Britain from its own vegetable gardens and maintain morale from its flower beds.

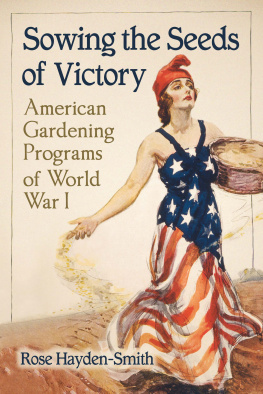

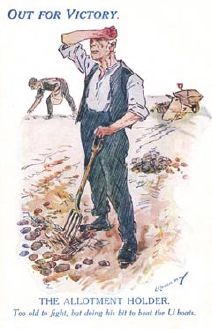

As an island nation, Great Britain had always been vulnerable to attack and blockade by sea and it was not until after the mid-twentieth century that substantial quantities of food were imported by air. The Napoleonic Wars (180315) forced increased home food production, expanded arable farming and raised food prices, leading in turn to civil unrest in 181520. In February 1915, just a few months into the First World War (191418), Kaiser Wilhelm II announced that both merchant and naval shipping in the waters around Great Britain would be destroyed without warning. The threat was renounced in 1916, but in February 1917 unrestrained U-boat warfare was reintroduced, with the aim of starving Britain into defeat. The response was a Victory campaign that included the creation of over a million allotments, and exhortations that those too old to serve at the front should do their bit to beat the U-boats in Britains fields and gardens. In 1917 Britains leaders had been unprepared for the impact of the German blockades and food shortages were a serious threat, especially as rationing was not put in place until 1918. Aptly, 1918 was the same year that Winston Churchill told to the poet and soldier Siegfried Sassoon that War is the normal occupation of man war and gardening, when the two crossed swords in parliament.

The First World War had seen a Victory campaign on allotments and gardens.

Britain had always looked to its gardeners to overcome the impact of war and blockades.

By 1938, when the possibility of a Second World War became a probability, the nation was even more vulnerable to blockades than in 1917. Population growth, combined with the expansion of the suburbs and a move away from a food-producing economy, brought heavy reliance on food imports. In 1938 over 55 millions tons of food were imported by merchant shipping, including many of the items traditionally regarded as essential to the national diet. Ninety per cent of onions came from mainland Europe, fruit came from South Africa and Australia, bread wheat from Canada and the United States, tomatoes were imported from the Netherlands or the Channel Islands, and even apples were brought from France, leaving the orchards of Kent increasingly neglected. Numbers of allotments had dropped dramatically after the end of the First World War, and, although some 1930s suburban houses had been created with gardens of an equivalent size to an allotment, many urban families were housed in cramped high-density housing and tenements. In 1939 a population of 45 million shared only 3.5 million private gardens. With an expectation that merchant shipping would again be the subject of blockade, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries calculated that, in such an emergency, private gardens and allotments could be made to produce a quarter of the nations non-cereal foodstuffs. But getting the nation to feed itself would necessitate far-reaching change.

Between 1939 and 1945 war transformed the nations gardens.

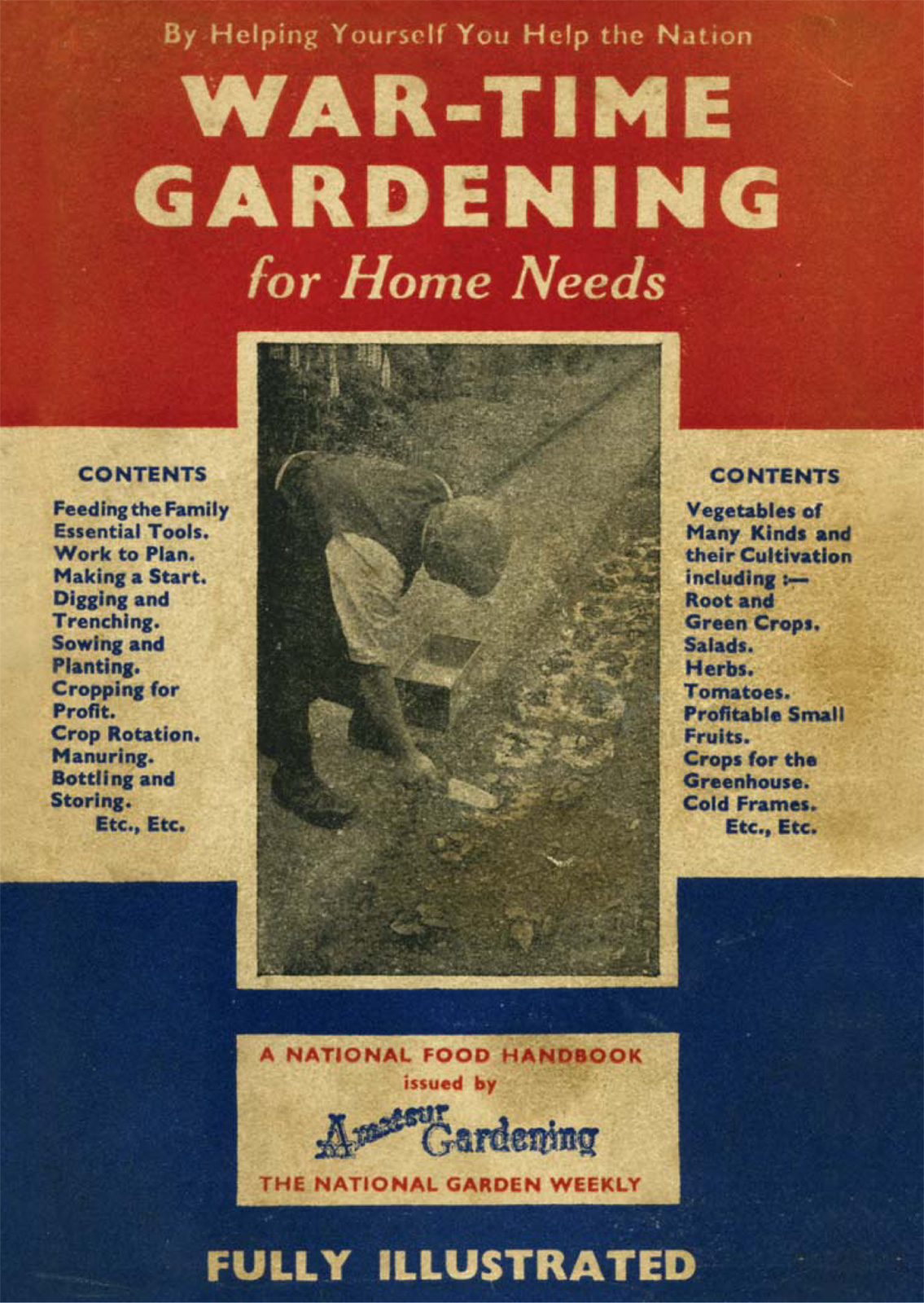

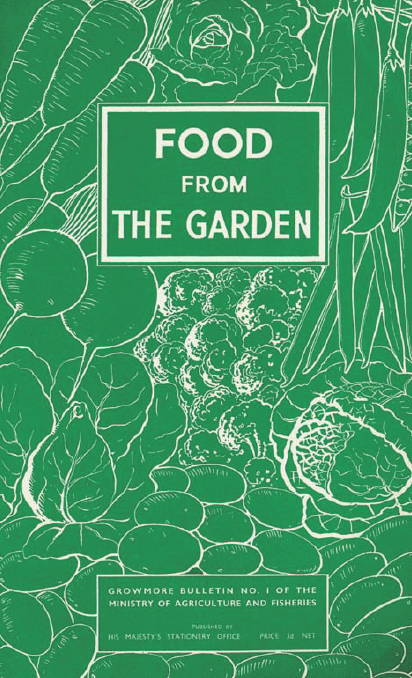

In the spring and summer of 1939 a small committee, its members drawn from the Royal Horticultural Society, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and the National Allotments Society, worked behind the scenes to produce the first strike from the Garden Front. Priced at 3d, Food from the Garden (Growmore Bulletin No. 1) aimed to inspire and inform the nations gardeners on the outbreak of war: its publication on 9 September 1939 put the gardens of Great Britain on a wartime footing. As the Gardeners Chronicle declared in its first edition after the outbreak of war (coincidentally also 9 September): Everybody whose whole time is not engaged in other forms of national defence, and who has a garden or garden plot or allotment, can render good service to the community by cultivating it to the fullest possible extent.

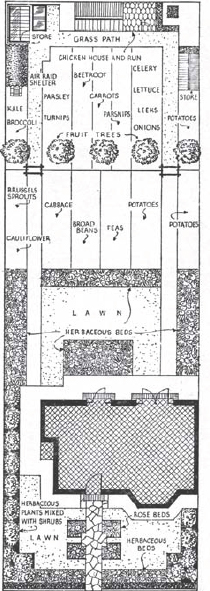

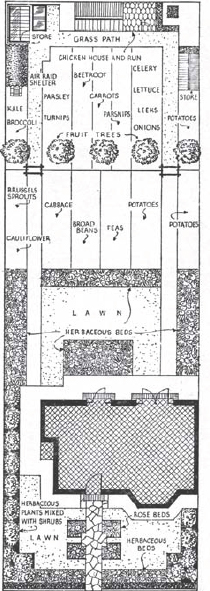

A typical 1930s garden adapted to wartime conditions, with the lawn under vegetables. Taken from Richard Suddells Practical Gardening and Food Production, published in 1940.

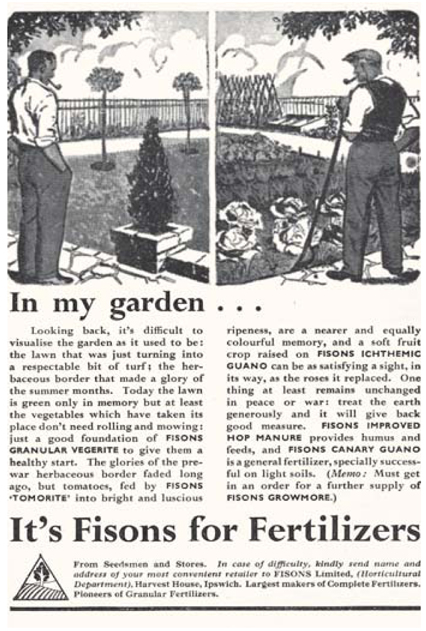

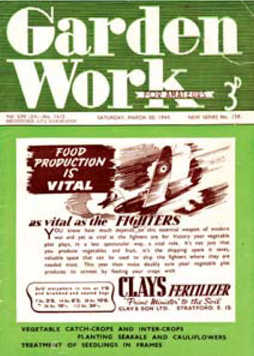

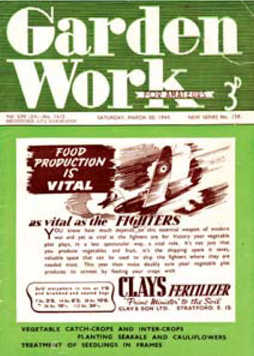

Home food production would play a vital role in winning the war by replacing food imports, as this advertisement explained.

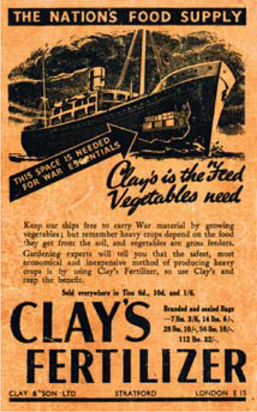

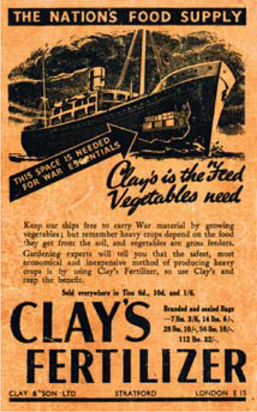

In wartime, there was no space for cargoes of food if it could be grown at home instead.

Food from the Garden was the first Growmore bulletin. Although largely superseded by shorter, free leaflets, there were two further bulletins aimed at the home gardener, on preserving foods, and pests and diseases.

Next page