THE TUDOR GARDEN

14851603

Twigs Way

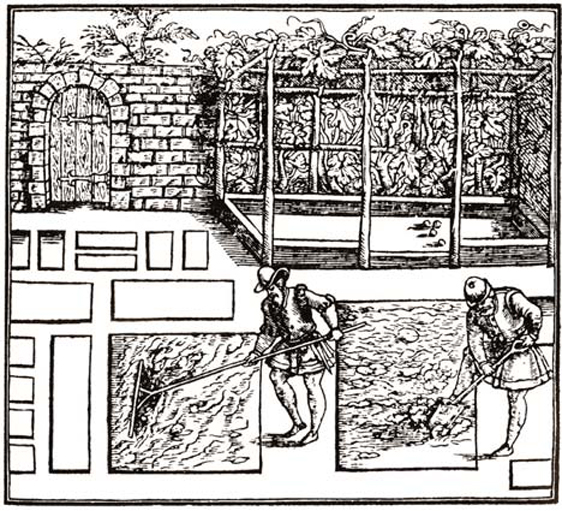

Detail from Adam Lonicers (1557) Krauterbuch of a plantsmans garden.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

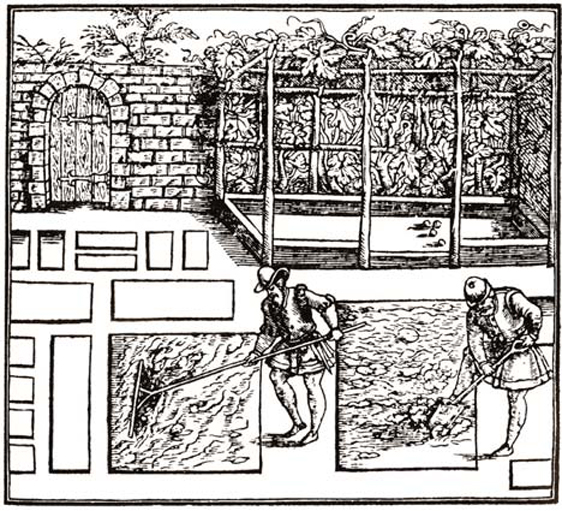

In collectors gardens, flowers were planted as individuals, rather than in groups, so that each could be individually admired. Raised beds also brought the plants closer to their admirers, as in this flower garden portrayed in the 1594 edition of Thomas Hills The Gardeners Labyrinth.

CONTENTS

The first page of an early edition of Thomas Hills The Proffitable Arte of Gardening. This work was based on his popular Briefe and Pleasaunte Treatyse on gardening, which had been printed in 1563.

INTRODUCTION

There lavish Nature, in her best attire,

Powres forth sweet odors and alluring sightes;

And Arte, with her contending, doth aspire

Texcell the naturall with made delights:

And all, that faire and pleasant may be found,

In riotous excesse doth there abound.

Edmund Spenser (1591) Muiopotmos (or the Fate of the Butterflie)

F ROM THE CORONATION of Henry VII in 1485 until the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the Tudor period was one of revolutionary change. Renaissance, reformation, empire and exploration combined to transform the lives and gardens of all but the very poorest in society. New plants from the old and new worlds, and new concepts from the classical and renaissance worlds, created opportunities for change whether in the most basic of productive gardens, or the magnificent extravagance of courtier and royal gardens. Our sources for the history of gardens also increase in this period. Maps and surveys, views, books, letters and even archaeology provide us with insights into the design and planting of the Tudor garden, as well as first-hand accounts of the garden experience. The scents and sounds, the sights, and the sheer excitement of the new are all captured in the words of travellers, courtiers, poets, and even gardeners, of the Tudor period.

It is with the words of gardeners, or at least garden writers, that the day-to-day workings of the typical Tudor garden are known to us, as the sixteenth century saw the birth of the garden book, and a consequent flourishing of manuals giving instruction in all aspects of planning, planting and even the philosophy of gardens. The first popular English gardening book appeared in 1563, written, or at least compiled, by Thomas Hill, an astrologer and book translator. Entitled A most brief and pleasaunte Treatyse, teachynge how to Dresse, Sowe, and set a Garden, the book was aimed primarily at the literate middling classes, the owners of small manor houses with combined productive and decorative gardens. The book was so popular that, under the rather catchier title The Profitable Arte of Gardening (1568 onwards), it was reprinted in numerous editions. Hills aim was to gather together in one book all the existing advice on gardening contained in the myriad classical works on plants and the more recent works on estate husbandry and farming, adding the usages of plants gained from books on herbs and physic. He added into this heady mix his own years of gardening experience, in the seasonal tasks to be carried out, and tools necessary for those tasks. The final work (by no means the Briefe treatise of its title) provided a complete guide for the Tudor gardener and garden owner, and also, through the woodcuts that accompanied later editions, a vision of the ideal Tudor garden. Building on his own popularity, although using the jocular pseudonym Didymus Mountain, Hill also brought out The Gardeners Labyrinth (1577), a title indicating labyrinthine knowledge, rather than designs for labyrinths, although it does include patterns for knot gardens. Hill dedicated The Gardeners Labyrinth to perhaps the most famous Tudor statesman and gardener, William Cecil (Lord Burghley) (152098), who thus forms a link between Hill and the other most famous writer of the period, John Gerard. Gerard (15451611), whose Herball, or General Historie of Plantes was written in 1597, was gardener to William Cecil at his house at Theobalds, where some of the rarest plants in the country could be found under his care.

Thomas Hills popular works give us an insight into the day-to-day operations in the Tudor garden, as well as glimpses of tools and tasks we still recognise today. This woodcut reminds us that gardens were for play as well as work, with a small raised bowling green in the background.

Using summer plants known in the sixteenth century, it is possible to create a jewel-box-like knot garden in the style favoured by the Tudors.

Games such as bowls, archery or Troco (shown here) were an important element of the enjoyment of gardens in the Tudor period, shown here in a painting of the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century.

This rare Tudor watering pot fills by being immersed in water; by then placing a thumb over the top hole a vacuum is created so that the water can be carried. When the thumb is removed, the water streams out of the multiple holes in the base.

Despite the clearly recognisable tools and actions from this sixteenth-century gardening text, and the fashionable raised beds, the planting style is very different from today. Individual plants were often accorded space to be admired at all angles. Here pride of place is being given to the Crown Imperial and other bulb plants.

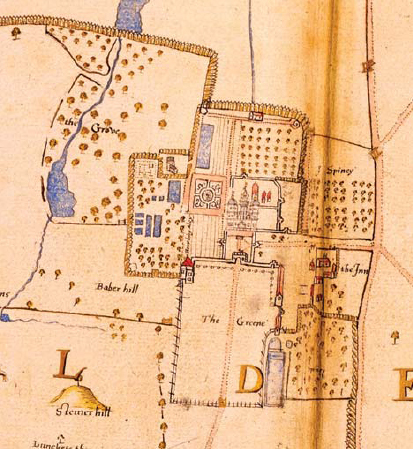

This 1587 plan of the gardens at Holdenby House (Northamptonshire) by Ralph Treswell allows us an insight into the layout of a typical Tudor garden. A long green forecourt and gatehouse lead to the house itself. The gardens around the house comprise orchards, bowling alley, and knot garden, all surrounded by wooden pale fence and set within a park.

The Tudor gardening world was a small one, and also linked to William Cecil was Francis Bacon, the opening to whose Essay on Gardens, that God Almighty first planted a garden and indeed it is the purest of human pleasures has been much quoted by gardeners ever since. Born in 1561, Bacon, son of Cecils sister Anne, was as much an Elizabethan as a Jacobean and had been a confidante of the ill-fated Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Although his