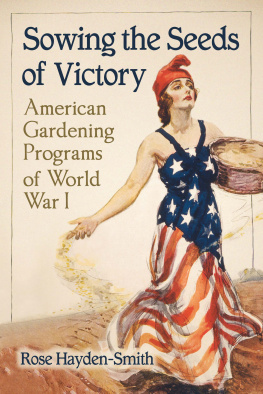

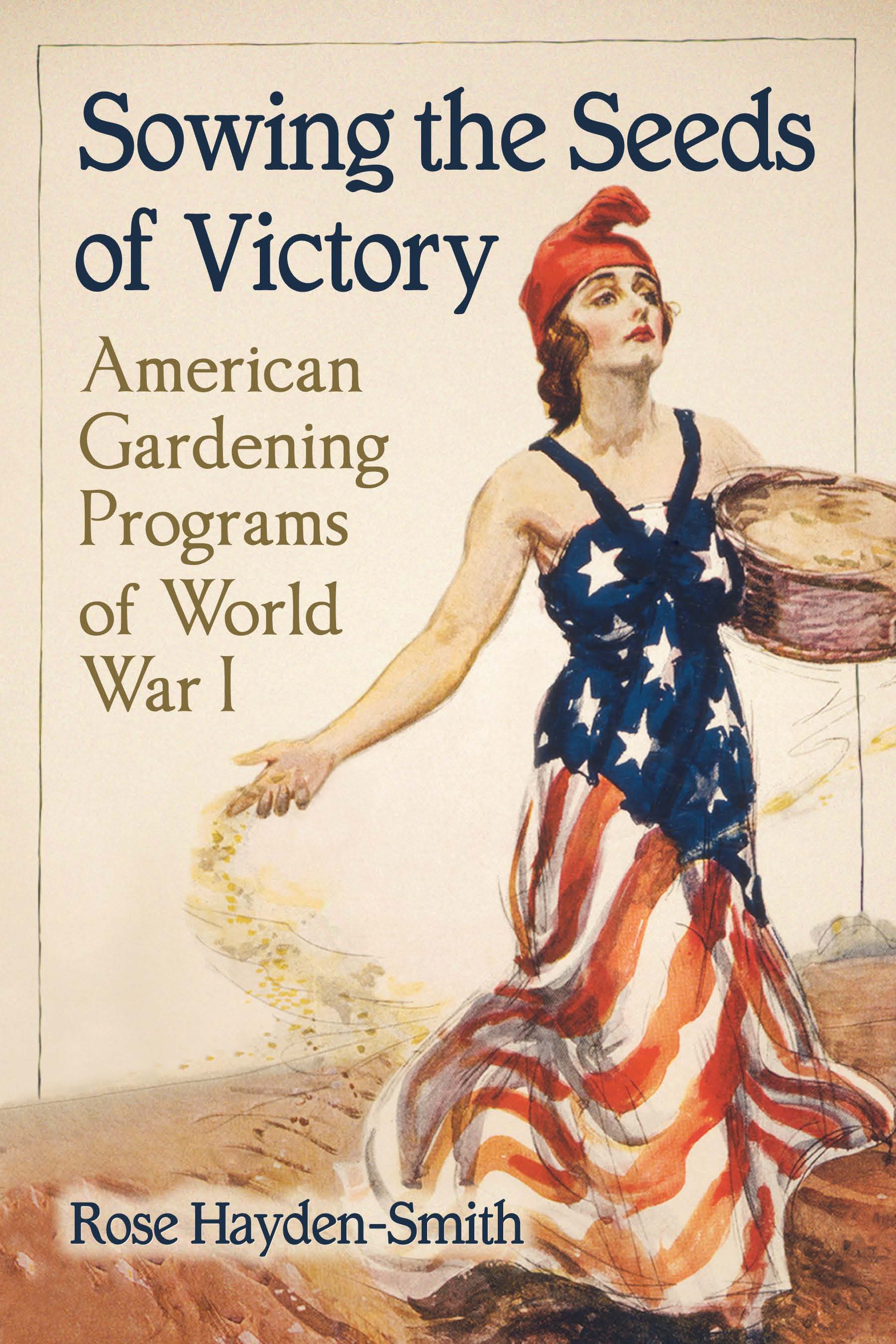

Sowing The Seeds Of Victory

American Gardening Programs of World War I

Rose Hayden-Smith

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1586-8

2014 Rose Hayden-Smith. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: World War I poster Sow the seeds of victory!artist James Montgomery Flagg, ca. 1918 (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Natalie

Wherever your path leads, your immense talents,

passion and love will surely fill some part

of the worlds deep hunger and need.

I love you to the moon and back.

For Daryl Wagar

Civic horticulturalist,

family man, friend

Acknowledgments

Good soil is the foundation of a good garden, and I owe deepest thanks for improving the foundation of my work to many people.

I am particularly grateful to the faculty at the University of California Santa Barbara History Department, including Dr. Randy Bergstrom, Dr. Lisa Jacobson, Dr. Ann Marie Plane, Dr. Mary Furner, Dr. Laura Kalman, Dr. Patricia Cohen, and Dr. John Majewski. I also offer gratitude to the friends who participated in UCSBs graduate survey course in United States history in 20022003 and to my colleagues at the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, particularly Dr. Daniel Desmond, who guided me into lines of applied research that have been avocational in nature and rewarding in ways I could not have imagined. Special thanks to my friend and fellow historian Dr. Maeve Devoy, who provided support at key moments and would not let me fail.

I am also extremely grateful to the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, the Thomas Jefferson Institute, and the Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy for their generous support in the form of a Food and Society Policy Fellowship and the ongoing opportunities they have provided to improve and further my work. Particular thanks are due to Susan Roberts, who challenged me to apply it in new ways and to see the broader public policy implications of my historical research. Deepest appreciation and affection to the Fellows of the W.K. Kellogg Foundations Food and Society Policy program: your work has inspired my own and you continue to support me in vital ways. You are family to me.

Historians build upon the work of other historians. In the course of a project, we often draw upon the work of many othersboth living and deadto inform our own work. I have had the privilege of meeting or speaking with some of those I most admire; their generosity, enthusiasm, and encouragement have been greatly appreciated. In no particular order, thanks to Dr. David Danbom, Dr. David Kennedy, Dr. David Glassberg, Dr. Amy Bentley, Dr. Laura Lawson, Dr. Robert Wiebe, Dr. David Potter, Dr. James Machor, Dr. Katherine Jellison, Dr. Stephanie Carpenter (who generously shared materials very early in my project), Dr. William Breen, Dr. Christopher Capozzola, Dr. William Cronon, Dr. William Leuchtenburg, Dr. Eldon Eisenach, Dr. Melanie Simo, Dr. Witold Rybczynski, Dr. Robyn Muncy, Dr. Douglas Sackman, Dr. Robert Cuff, Dr. Harvey Levenstein, Dr. Margaret Rossiter, Dr. Nancy Cott, Valencia Libby, Elaine Weiss, Catherine Kipp, Rae Eighmey, and Martha Nolan.

Gardeners and those who study gardening are the most generous and kind people. To the many librarians, archivists, horticultural experts and gardeners who supported this endeavor: thank you. I am especially indebted to a local institution, the Museum of Ventura County, which works in my community to educate about the importance of agriculture in all our lives. I have visited dozens of gardens (and gardeners) each year, all across the United States: home gardens, gardens small and large, informal and formal, school gardens, botanical gardens, country gardens and city gardens, gardens for children, gardens for seniors, gardens at workplaces, community gardens, gardens that are public-purposed, and farming enterprises that are transforming the food system. Each growing place I visited provided a profoundly moving experience and demonstrated that the Victory Garden model is alive and well.

The roots of this project run deep and are highly personal. My deepest roots are in my family, friends and community. Warmest thanks to my husband, Bill, who mobilized the resources of our familys home front over a period of many years to make this book possible. Our daughter, Natalie, was also helpful and often traveled with me on research trips. She and her peers provided opportunities to share my interests in gardening and food systems education as they were growing up. When I began to study this topic, Natalie was small and stood on a chair to copy pages of books and journal articles for me at UCSBs library. Time marches on; it was she who typed the final citations in my dissertation, which was the genesis of this book.

While those who have worked with me are a critical component of this book and are reflected in it, any errors, omissions or failings are wholly mine.

Preface: Sowing the Seeds of Victory

During World War I, students at the small Ann Street Elementary School in my community of Ventura, California, raised two tons of potatoes in their school garden. Their work, replicated in thousands of schools across the United States, had its roots in a broader national imperative that mobilized citizens of all ages to help boost wartime agricultural production and encourage consumption of local foods. While these national programs encouraging home, school, and community gardening reflected cultural, social, and political conditions specific to the World War I era, they established a public practice that has been revisited during war and other trying times. Today they contribute to national sustainable food systems initiatives.

This book explores the implications of Americas national gardening and food production programs during World War I in a historical context. The programs provided models for community food production not only in a later war (World War II), but also in a contemporary settingtodaycast as an analogue of war. Perhaps it is not so remarkable that the histories of these wartime food projects are seriously considered now within the context of creating a more sustainable food system in America. Public commentary, advocacy and scholarship have heightened concern for the public health, environmental, and strategic aspects of food production. Scholars, policy makers and producers recognize that the sustainability of agriculture is a serious challenge not only to our nations security, but also to the public welfare generally, and not only nationally, but also globally.

Never have food and agricultural policy discussion been so mainstream and never have food and agriculture been connected more explicitly. Early in President Barack Obamas first administration, a department in the USDA was reorganized into the National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA), echoing the organization of the National Institutes of Health.

Next page