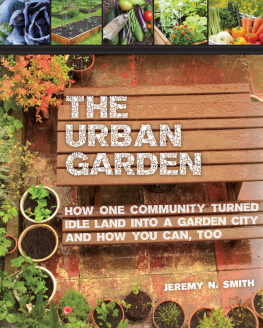

The Spade as Mighty as the Sword

And he gave it for his opinion, that whoever could make two ears of corn, or two blades of grass, to grow upon a spot of ground where only one grew before, would deserve better of mankind, and do more essential service to his country, than the whole race of politicians put together.

Jonathan Swift, Gullivers Travels

On 19 March 1941, a woman by the name of Joan Strange updated her personal diary (subsequently published as Despatches from the Home Front). Help! Ive not written this old diary for nearly a week, she wrote. Its the allotments fault! The weather has been so good that Ive gone up most evenings and get too tired digging to write the diary.

Joan was a member of one of the British nations essential fighting forces, waging a daily battle on what was to become known as the Garden Front. Through dint of hard work, frugality and inventiveness, Joan and millions of others like her ensured the nation remained sated during the Second World War. No longer able to guarantee the international imports on which the nation had for too long relied for its food, the British government had set about persuading its people to live off the fat of its own land. Those not fighting on the front lines took up the challenge with gusto, joining an army of growers united by the clarion call Dig for Victory. The authorities hoped the campaign would help the United Kingdom avoid the food shortages that almost proved so catastrophic during the First World War, while boosting levels of nutrition and morale amongst the public, and freeing up shipping for other vital supplies instead.

Joan herself had grown up in Worthing during the First World War and was a most eager horticulturalist by the time of the Second World War. But even as hardy a grower as she occasionally felt the strain. On 3 May 1941 she noted: For four weeks I have had acute neuritis in my right arm thanks to digging for victory in the north-east wind in the evening! However, as any good gardener will attest to, there are always rewards for the pain and toil. A mere month later, her joy was apparent as the first crops emerged: The allotment is looking wonderful and I cut 2 lb of spinach today the first fruits! Through such efforts the Diggers for Victory would harvest a million tons of produce per year at the campaigns peak.

Within the space of eighteen months at the start of the war, the campaign helped reconfigure the national landscape and the lives of its citizens. In villages and towns up and down the country, every available scrap of spare land was given over to the cause. Lawns, flower beds, parks and playing fields, tennis courts, railway sidings, window boxes, even the grass verges at the side of the road all were turned over to food production. In a 2006 Royal Horticultural Society documentary on the campaign, one contributor called Fred Ferebee remembered returning to his family home in Southwark after a period in the country as an evacuee:

I got back home and noticed some amazing changes The biggest change was in the small back garden Dad had changed everything bar one rose over a trellis which he loved And everywhere was planted with runner beans and peas and tomatoes, lettuce, everything you could imagine.

The government reported in 1942 that over half of all households were growing at least some of their own veg. Men, women and children of all backgrounds pooled their efforts. Sunday afternoon was a particularly popular time to get the veg patch straight, though many more hours besides were spent cultivating and nurturing. Even the church got in on the act, delivering messages of encouragement to the amateur grower from the pulpit. Oft used as the starting point of such sermons was Proverbs 28:19: He that tilleth his land shall have plenty of bread. Bread and much more, in fact! One Kent schoolboy reminisced on the excitement of digging small carrots on the allotment, selecting one, cleaning it on my sleeve and biting into its fresh crispness!

The pleasure in success was only heightened by the physical dangers under which growers laboured. Herbert Brush of Forest Hill reported in his diary on 26 October 1940 (quoted in Our Longest Days by Sandra Koa Wing) on the impact of a German bombing raid: I went round to look at the allotment, but it was a case of looking for the allotment. Four perches out of five are one enormous hole and all my potatoes and cabbages have vanished.

With food supplies growing ever shorter as the war progressed, a few fresh veg could turn an otherwise dull dish into a veritable feast. As such, produce became increasingly valued. An organised barter market sprung up in Croydon, where growers could exchange surplus produce for vouchers to buy clothes and other goods. Elsewhere, there were village raffles offering first prize of a giant onion or some other such delicacy. In innumerable villages and towns, growers armed with shovels and buckets could be seen sprinting down the street after the coalmans cart, hopeful of winning the race for priceless horse manure to spread on their crops. People proudly displayed signs on their garden gates proclaiming, This is a Victory Garden.

Remarkable acts of cooperation became commonplace, from the Gloucestershire village that united to grow potatoes in commercial volumes to the north London dustmen who recycled the waste they collected to feed the pigs they had started to keep. Perhaps most remarkable of all were the residents of Bethnal Green who, pummelled by Nazi air raids, took the land where bombed-out homes and schools once stood and turned it into fertile ground for growing.

Yet more people took on the challenges of animal husbandry for the first time. Rabbit hutches and chicken coops appeared in countless back gardens. Houses were filled with the mysterious aroma attached to the cooking of chicken feed. Others kept beehives to produce their own honey, or joined pig clubs in the hope of feasting upon choice cuts while others had to make do with their minimal bacon rations. On street corners in every major town and city there were pig bins into which citizens were encouraged to deposit their food scraps for porcine sustenance. All this from a nation that, before the war, had looked abroad for its food.

Now among the most fondly remembered of any government initiative in history, the success of the Dig for Victory campaign relied on remarkable feats of organisation, inspired publicity campaigns and a will among the people to undertake whatever they could to do their bit. In an address on the BBC on 27 April 1941, Winston Churchill gave his own typically stirring assessment of the desire on the Home Front to contribute:

Old men, little children, the crippled veterans of former wars, aged women, the ordinary hard-pressed citizen or subject of the King are proud to feel that they stand in the line together with our fighting men, when one of the greatest of causes is being fought out, as fought out it will be, to the end. This is indeed the grand heroic period of our history, and the light of glory shines on all.

On 12 June 1940, an article appeared in the Manchester Guardian, headlined Half an Acre. The writer, identified only as D., described the new experience of growing your own. In an understated tone, it speaks of a new way of life and tells a story repeated throughout the country:

Now the potatoes are coming along in eighteen rows, the beetroot is showing strongly, and although the carrots are a mystery and the first two rows of scarlet runners, sown against the weight of local advice, were nipped by a May morning frost the townsmen never heard of, their successors are already running an exciting race with the peas. We are eating our own radishes and spring onions and shortly the infuriating experience of paying four pence for a lettuce will be no more. The celery and the marrows are in. It has all been good fun and good exercise and we are getting proud of it. In fact we now refer to the cottage as The Farm.