CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

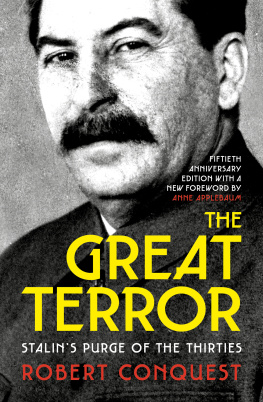

Robert Conquests The Great Terror is the book that revealed the horrors of Stalins regime to the West. This definitive fiftieth anniversary edition features a new foreword by Anne Applebaum.

One of the most important books ever written about the Soviet Union, The Great Terror revealed to the West for the first time the true extent and nature Stalins purges in the 1930s, in which around a million people were tortured and executed or sent to labour camps on political grounds. Its publication caused a widespread reassessment of Communism itself.

This definitive fiftieth anniversary edition gathers together the wealth of material added by the author in the decades following its first publication and features a new foreword by leading historian Anne Applebaum, explaining the continued relevance of this momentous period of history and of this classic account.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Robert Conquest (1917 2015) was one of the twentieth centurys greatest historians of the Soviet Union. Publication of The Great Terror: Stalins Purge of the Thirties in 1968 brought him international renown, as did his revelatory later history The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine published in 1986. As well as holding academic posts at various universities, including the London School of Economics, Columbia University and Stanford University, he was an acclaimed poet, critic, novelist and translator.

Also by Robert Conquest

Non-fiction

Power and Policy in the USSR

Common Sense about Russia

Courage of Genius: The Pasternak Affair

Russia after Khrushchev

The Great Terror

The Nation Killers

Where Marx Went Wrong

V. I. Lenin

Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps

Present Danger: Towards a Foreign Policy

We and They: Civic and Despotic Cultures

What to Do When the Russians Come (with Jon Manchip White)

Inside Stalins Secret Police: NKVD Politics 19361939

The Harvest of Sorrow

Stalin and the Kirov Murder

Tyrants and Typewriters

The Great Terror: A Reassessment

Stalin: Breaker of Nations

Reflections on a Ravaged Century

The Dragons of Expectation

Poetry

Poems

Between Mars and Venus

Arias from a Love Opera

Coming Across

Forays

New and Collected Poems

Demons Dont

Verse Translation

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyns Prussian Nights

Fiction

A World of Difference

The Egyptologists (with Kingsley Amis)

Criticism

The Abomination of Moab

For my sons, John and Richard

FOREWORD

BY ANNE APPLEBAUM

More than four decades ago, back when the Soviet Union still existed and the Berlin Wall still stood, the KGB searched the apartment of a Russian friend of mine. Inevitably, they found what they were looking for: his large collection of samizdat illegally printed magazines and books. They pounced on the bleary mimeographs, rifled through them, put some aside. One of them held up my friends contraband copy of The Great Terror in triumph. Excellent, weve been wanting to read this for a long time, he declared. Or words to that effect.

Nowadays, its difficult even to conjure up the background necessary to explain that scene. Can anyone under forty imagine a world without satellite television and the Internet, a world in which television, radio and borders were so heavily patrolled that it really was possible to cut a very large country off from the outside world? In the Soviet Union, that kind of isolation was not only possible, it was successful. Soviet leaders controlled and distorted their history so much so that their own policemen were unable to find out the truth from their own writers, in their own language. There was always a vast gap between the official versions of the past on the one hand, and the stories that people knew from their parents and grandparents on the other. That gap made people curious, hungry to know what had really happened even people who worked for the KGB.

In that world, a single book could have an enormous impact. From the time of its publication in 1968 a moment when it went very much against the grain Robert Conquests The Great Terror was one of those that did. Of course the story that it told was hardly unfamiliar inside the USSR. In 1956, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had made his famous secret speech, denouncing the mass arrests, especially mass arrests of party members, that Stalin had carried out in 193738, the era of the Great Terror. But the speech was never officially published, and its catalogue of Stalins crimes was incomplete. More importantly, the impact of the speech, although electrifying at the time, did not last. Khrushchevs reign as Soviet leader was relatively short, and by 1968 Leonid Brezhnev had begun imposing a new version of Stalinism. History inside the Soviet Union had once again been stultified , public debate had stopped, and the brief literary and artistic Thaw had come to an end. At that moment, despite Khrushchev, the true history of the terror of 193738 still could not be told. The details were once again in dispute. For Soviet citizens who had access to it, or who managed to hear about it, Conquests book once again opened a closed door.

But Conquest was also writing for the benefit of the West, which was in 1968 still engaged in a real struggle against the temptations of Soviet totalitarianism. In 2008, Conquest himself reminded his younger contemporaries of just how existential this struggle had seemed. He quoted the French historian Francois Furet: All the major debates on post-war ideas revolved around a single question: the nature of the Soviet regime. This idea that all important political debates once revolved around communism is now as hard to understand or believe as the closed world of the USSR itself. But in the 1960s, the history of the Soviet Union mattered to Western Marxists, and indeed to Western anti-Marxists, far more than we now remember. It mattered because it had implications for the present. Was the tale of Lenins revolution a story of success and triumph, or was it a tale of tragedy? Did the Soviet Union therefore herald a new paradise on earth, or was it a macabre charade? Conquest always knew that The Great Terror would play a role in this urgent and important public debate. By documenting the terror of the 1930s, the arrests and executions, the prisons and the torture chamber, Conquest made a powerful argument for tragedy and for the fundamental falseness of the Soviet vision as well.

Conquests moral and political commitment to anti-communism his passionate belief that it mattered how the West perceived the USSR shaped his book in numerous ways. For one, it changed the way he did research. At that time, there were no real archives available, because the Soviet state kept all of its records secret. Although the Soviet press, and official Soviet histories, were accessible, they were profoundly deceptive, distorted by official propaganda. They did not tell the story of 193738, did not explain what had happened to the Bolshevik elite during those years, did not tell the full story of the show trials or mass arrests. Conquest used what was available judiciously, but also used a third source: eyewitnesses, migrs and defectors who were often, at the time, dismissed as biased'. They didnt understand great power politics, it was said; or they bore grudges; or they didnt realise that they were unimportant casualties on the road to the communist utopia.