We were born to make fairy tale [skazka]fact

propaganda verse, extolling the heroism of the Soviet Air Force

We were born to make Kafka fact

unofficial wit, reflecting the reality of the Soviet experience

The fiftieth anniversary of Stalins death, March 5, 2003, marked a moment of reflectionand concern for manyon the legacy of Russias Soviet past. Former prisoners can remember being woken to the tune of Stalins national anthem in the Gulag. Apparently, the country is suffering from some form of political amnesia.

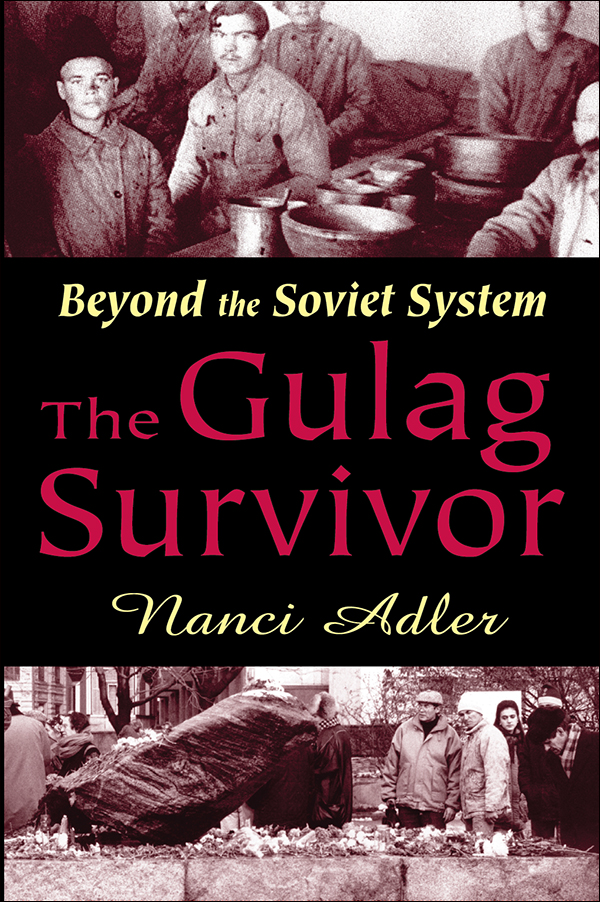

One of the specters of Russias past that regularly appears to haunt its present is that of fallen Soviet idols, complete with their emblems and anthems. In December of 1998 the Russian State Duma voted in an overwhelming majority to restore the statue of Feliks Dzerzhinsky to the platform in front of Lubyanka from which the founder of Lenins Cheka (secret police) had been so ceremoniously toppled seven years earlier. The Duma resolved that returning Dzerzhinsky to his place would prove an important step in the preservation of the historical-cultural heritage of Russia and would serve as a symbol in the struggle against crime.

While the Cheka founder was not resurrected, the motion was raised once again. In the fall of 2002, Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov called for the statues return to its former place of honor. He noted Dzerzhinskys good deeds in establishing orphanages Luzhkovs proposal may have been aimed at political benefits for pleasing President Putin, a former KGB career officer. It was supported by the Communist, nationalist, and agrarian parties, but ultimately blocked by critics.

Another telltale sign of public memory lossor political amnesiahas been detected in population surveys. A February 2003 public opinion poll taken among 1,000 residents of St. Petersburg reported that 45 percent of the respondents maintained a favorable view of Stalins role in Russias history, while 38 percent looked upon the dead leader negatively.

Who and how to remember and commemorate can be daunting questions for a society recovering from seven decades of state-sponsored repression. Russias ambivalent struggle to come to terms with its repressive and onerous past has been going on for half a century. On a political and societal level, starting in the fifties, entrenched officials attempted to address these issues in their efforts to distance themselves from the Stalinist past. At the same time, Gulag victims returning to society confronted every individual with whom they came into contact with a reality about the nature of the system and the mentality it nurtured that many did not want to see or think about. Indeed, the way in which the victims of Soviet terror returned and were returned to society touches upon some of the most complicated questions in Soviet history and in Russias continuing search for accountability and direction. What, for example, does it say about the credibility of a system in which many believed when an individual (or millions of individuals) endures seventeen years in prisons and labor camps, and then is declared an innocent victim, yet the perpetrator is left unnamed? In one sense, the perpetrator was, to borrow Vaclav Havels argument, everyoneneighbors, colleagues, friends, and family members who were induced to go along with the system for personal gain or out of fear. In another sense, the perpetrator was no one in particular. It was the system as a whole, with pervasive terror as its adaptive tool. The Soviet dictatorship lasted for over seven decades, so the pathology that extended from the top down, and from the bottom up, had a long time to take root and develop. These fundamental issues will be considered throughout the present work because they are at the very core of the Gulag returnee question.