Khrushchevs Cold Summer

Gulag Returnees, Crime, and the

Fate of Reform after Stalin

MIRIAM DOBSON

Cornell University Press

ITHACA AND LONDON

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Part I. Re-imagining the Soviet World after Stalin, 19531956

1. 1953: The Most Painful Year

2. Prisoners and the Art of Petitioning, 19531956

3. Heroes, Enemies, and the Secret Speech

Part II. Stalins Outcasts Return: Moral Panic and the Cult of Criminality

4. Returnees, Crime, and the Gulag Subculture

5. The Redemptive Mission

6. A Return to Weeding

Part III. A Fragile Solution? From the Twenty-Second Party Congress to Khrushchevs Ouster

7. 1961: Clearing a Path to the Future

8. Literary Hooligans and Parasites

Conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

I would first like to thank the funding bodies that enabled me to complete this book. During my first three years at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) in London, the Arts and Humanities Research Board offered generous financial support, and a Scoloudi Research Fellowship from the Institute of Historical Research allowed me a precious writing-up year. Additional grants from the University of London Central Research Funds, University College London, SSEES, and the Royal Historical Society helped enormously with travel costs. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield for granting me research leave during my second year working here, and to the British Academy for funding a much-needed archive trip during that sabbatical.

Over the nine years that I have been working on this project many people have helped me. Susan Morrissey was an amazing adviser, pushing me to think without forcing me toward any one conclusion. On a personal level, she was extraordinarily supportive, seeming to know instinctively when to be demanding, and when to remind me that theres more to life than Russian history. Others also provided important encouragement along the way. Chris Ward was an inspirational undergraduate teacher, and Geoffrey Hosking has given me great support throughout, always asking probing and insightful questions of my work. Two of the most rigorous readings of my work came from Steve Smith and Stephen Lovell, and as I revised and rewrote my manuscript their detailed and incisive comments proved absolutely invaluable. Many others have discussed my ideas, read drafts, or helped with translations and queries, and I would like to thank all of them, in particular Steve Barnes, Yoram Gorlizki, Maya Haber, Cynthia Hooper, Hubertus Jahn, Polly Jones, Ann Livshchiz, Ben Nathans, Holger Nehring, Kevin McDermott, Rachel Platonov, Susan Reid, Kelly Smith, Claudia Verhoeven, Amir Weiner, and Benjamin Ziemann. In the books final stages, the input from Cornell University Press has been outstanding: I am particularly grateful to John Ackerman, Karen Laun, Carolyn Pouncy, and the two anonymous reviewers. Sections of chapter 8 appeared in Slavic Review (vol. 64, 3 [Fall 2005]) and are reprinted here with the permission of the American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies.

The support I received while conducting research in Russia made this project possible. There are many people in the libraries and archives of Moscow, Vladimir, and Cheliabinsk who helped me. Special thanks go to Leonid Weintraub, Elena Drozdova, and Galina Kuznetsova, who started me on the right path. My biggest debt of gratitude must lie with Denis Klimov and Natasha Kurdenkova for sharing their home and friends with me for almost a year. I am also grateful to Pavel, Masha, Dima, and Nastya for their warm hospitality each time I go back. The late Svetlana Zamiatina was an inspiring friend, and I thank Eduard Kariukhin for introducing us and for his support while I was living in Moscow.

During my post-graduate study, SSEES offered a stimulating environment: staff at the library have always been helpful and the Centre for Russian Studies offered a friendly forum for debate. Fellow doctoral students helped make London a great place to live and study, especially Nick Sturdee, Bettina Weichert, and Maya Haber. Penny Wilson and Kate Wilson were incredible friends and flatmates during these years and helped in many ways. Since I moved to Sheffield four years ago my colleagues have been supportive and interested, offering useful guidance as I began the process of revising my manuscript. My family deserves special thanks for their encouragement, and I particularly appreciate the enthusiasm with which my parents Heather and Mike came to visit me in Russia. Last but not least, all my love goes to Thomas Lengknowing him makes it harder to go to Russia, but so much more fun to be at home.

Introduction

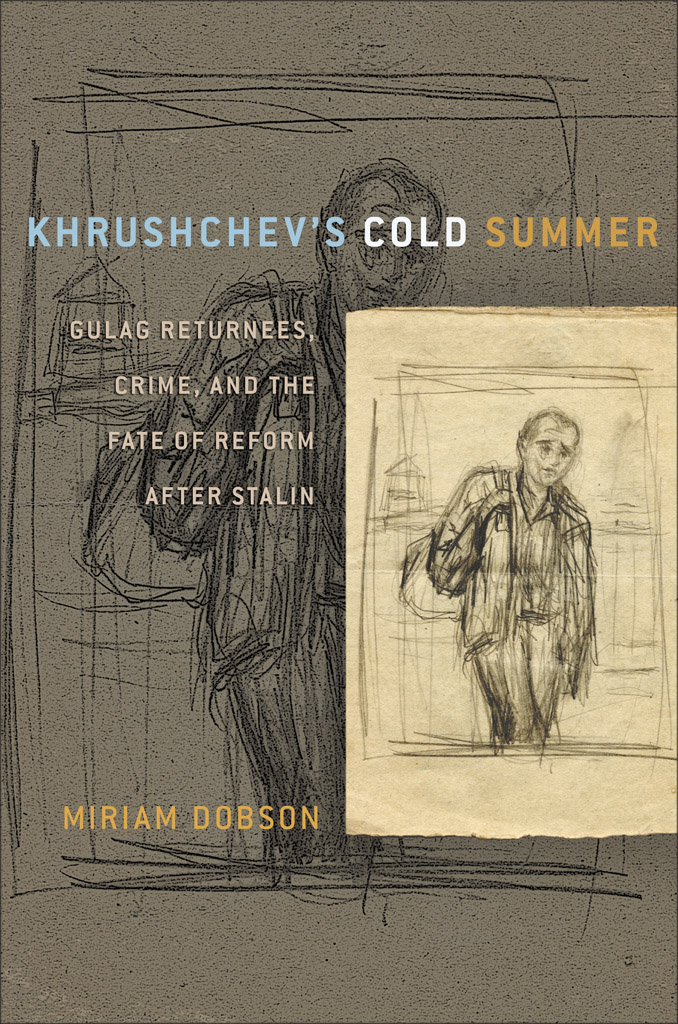

Cold Summer of 53, a film of the perestroika era, opens in an isolated fishing hamlet. Under the boundless expanse of the northern skies, an unkempt man flirts with a pretty young girl washing the family laundry at the edge of a river. Her mother, a mute, opposes the friendship between the two, at one point throwing a bucket of cold water over them both. Her reasons soon become clear: having served a prison sentence for treachery during the Second World War, the man lives in the hamlet as an exile and, although the villagers know him, he remains an outsider to the community.

The first few scenes of Cold Summer of 53 have an elegiac feel, but the rural calm is soon violently disrupted. Viewed by one critic as the Russian answer to the American western, the film goes on to portray a brutal conflict in which bandits arriving from the outside world rip apart the harmony and security of the tiny rural settlement. In the spirit of a traditional western, the film requires both heroes and villains. The latter come in the form of a group of armed bandits, released from the Gulag by the amnesty of 27 March 1953. Terrorizing the countryside as they make their way back across Russia from the camps, they are organized, violent, and merciless: the villagers are held hostage, the girl narrowly escapes rape but is later killed. The role of hero is taken not, as a Soviet audience might have expected, by a local party official or policeman, but by the shabby exile. Alongside an old comrade, also a former political prisoner, he courageously engages the brigands in a dangerous shoot-out. The risk pays off. The protagonist kills the bandits, and the village is saved. The villagers are forced to recognize that despite his status as exile, the protagonist has rescued them; and yet most still remain wary of him. Despite his heroics he is still not fully reintegrated into Soviet society: the last shot of the film sees the hero two years later wandering the streets of the capital carrying his suitcasealone.

Aleksandr Proshkins 1988 film told the story of the first wave of Gulag releases following the death of I. V. Stalin on 5 March 1953. Long an outpost for those deemed unfit to remain within the Soviet family, the Gulag was dramatically downsized between 1953 and 1960. The population of the camps and colonies, which stood at almost 2.5 million on the eve of Stalins death, would shrink nearly five times over the course of these seven years. In addition to the prisoners in camps and colonies, almost three million people were enduring some form of banishment in 1953, and the majority of these saw their exile status revoked by the beginning of the 1960s. Although the regime tried to protect key cities and major industrial centers by placing restrictions on the movement of some returnees, in practice few points in the Soviet Union remained untouched as millions of Stalins outcasts began wending their way back from the most remote areas of the country.