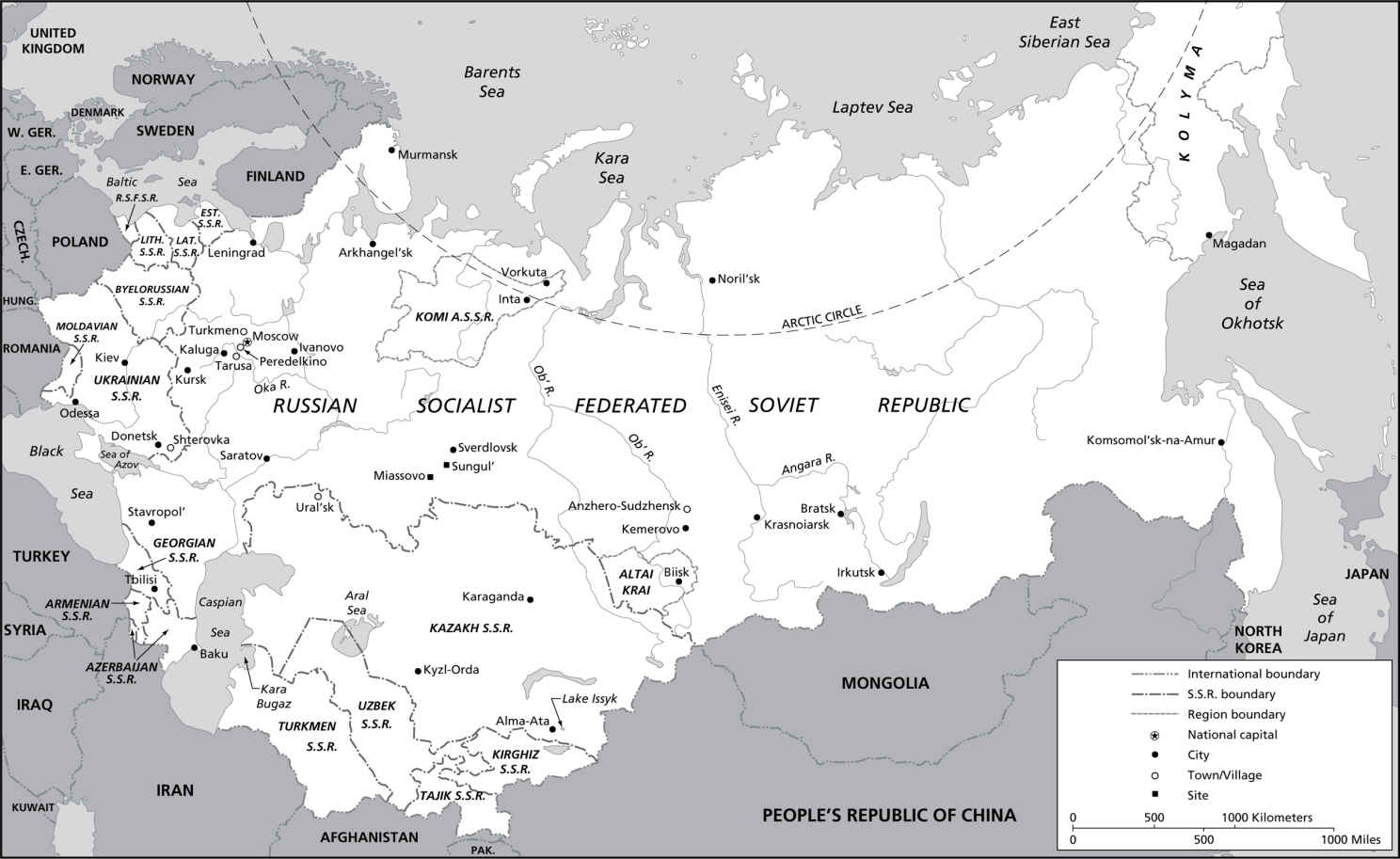

The Soviet Union in 1956.

As the year 1956 dawned in Moscow, Joseph Stalin had been dead for nearly three years. His preserved corpse lay alongside Vladimir Lenins in the mausoleum on Red Square. Just over the wall in the Kremlin, however, pressure had been building for months among members of the Communist Partys ruling presidium about how to handle the late dictators mixed legacies. Stalin had aggressively promoted industrialization and led the Soviet Union to victory in World War II, but he had also purged his rivals, sanctioned mass arrests of innocent people, and built a monopoly on power centered on a cult of personality. After Stalins death, his heirs had quickly backed away from a looming show trial and reined in the secret police. However, they had acted with little commentary. Nikita Khrushchev was about to change that.

On February 29, 1956, writer Lidiia Chukovskaia, whose husband had been executed during the purges, wrote in her diary: Rumors, rumors, you cant make out anything. Can it be that weve lived to hear the Word? It would be another month before she heard Khrushchevs Secret Speech read out loud at the Writers Union. But she had indeed survived to learn that judgment on Stalin had been pronounced from on high. Four days earlier, the partys own first secretary had stunned a closed gathering of the political elite by recounting appalling facts about the terror that had been unleashed in the name of the revolution. Over the course of a few hours, Khrushchev shattered the myth of Stalins infallibility and promised that a restored collective leadership would bolster socialist legality and undo the harmful practices of the Stalin cult.

Starting in March 1956, Khrushchevs confidential report to the Twentieth Party Congress would be read out to a broader audience of party and youth league members and civically active persons across the Soviet Union. For the cult of Stalin to be dissolved, its millions of adherents had to learn how the late leader had violated Marxist-Leninist norms. Before they encountered survivors of the gulag, Soviet citizens needed to know that the party had already recognized and corrected its errors.

Khrushchev acted out of conviction that the party would be strengthened by acknowledging and addressing problems caused both by the erosion of collegiality within its ranks and the elevation of Stalin to godlike status. In his report to the special session of the Congress, the first secretary did not delve into the larger record of coercion and violence that marked the span of Soviet rule; he recognized only a few of the worst abuses of the Stalin era. However, Khrushchev believed that a dose of truth telling could emancipate the post-Stalin leaders emotionally and practically from their adherence to past practices and policies. Well aware of the peoples dire need for housing and their desire for a higher standard of living, Khrushchev gambled that promoting peace abroad and reinvigorating management at home would boost the economy and with it popular support. He expected the restoration of the great moral and political strength of our Party promised in the Secret Speech to produce a cascade of positive outcomes.

However, while Khrushchevs bold act spawned genuine admiration and enthusiasm in some quarters, it also gave birth to myriad unintended and sometimes profoundly unwelcome consequences. The wide practice of criticism and self-criticism that Khrushchev claimed ought to characterize party life proved hard to handle in practice, especially as the Report on the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences raised questions about the accountability of the current party leaders. Moreover, the denunciation of the practice of whitewashing flaws in the Soviet economy encouraged writers, journalists, and engaged citizens to tackle current issues more bluntly. Chukovskaia and other members of the intelligentsia in particular would struggle in 1956 to understand what it meant to lift the constraints of the cult of Stalin within the framework of a monopolistic ruling party. How far did the limits of criticism stretch? Who would be the regimes new heroes and villains? How could liberation be combined with renewaland under whose terms?

While the Soviet government coped with pressure from its intelligentsia for more freedom of speech and more access to the outside world, genuine popular unrest broke out in two of its central European satellites in 1956. The year would end with Khrushchev scrambling to defuse discord in Poland and suppress an armed uprising in Hungary. These events would strengthen the position of those who feared that the Secret Speech had damaged the regimes standing. In December, with Khrushchevs acquiescence, they would turn the party apparatus against reformers who had taken up the tasks laid out by Khrushchev and against young freethinkers who had begun to call for more popular control over politics. The spring would be silenced at least temporarily.

For the Soviet Union, 1956 became a year of optimism and disillusionment, of painful revelations and gratifying debates, of hopes raised and disappointed. During this intense period of social, cultural, and political turmoil, people from all walks of life attempted to sort out what it meant that the patriotic narrative of progress toward a communist utopia had been tarnishedbut presumably not upendedby Stalins megalomania, paranoia, and mass persecution of innocent people. Meanwhile, Khrushchev and other party leaders wrestled with challenges to their notion that political changes could and should be orchestrated and directed from above. Khrushchev assumed the masses would respond enthusiastically to a fresh commitment to a more approachable and responsive government. He did not expect that young people especially would demand more freedom and more trust than he was ready to yield.

Half a century later, veteran human rights activist Ludmilla Alexeyeva would recall of her generation, Of course, our development began before the Twentieth [Party] Congress, [but] it constituted a shock for us, because we all knew but had never heard [about Stalins repressions] from the lips of the leader of the country. We instantly sided with Khrushchevpsychologically we were already children of the Twentieth Congress. Other intellectuals participating with Alexeyeva in a 2006 seminar on the Sixties Generation concurred that although some reforms predated Khrushchevs speech and while cultural liberalism had thrived most vigorously in the 1960s, one could fairly say that: The sixties generation was born on the day of the Twentieth Congress. The self-censorship ingrained under Stalin had taken a major blow, and as a result a new culture of discussion and debate emerged among artists, writers, scientists, university students, and the like. Pent-up questions and fresh opinions would spill over into the public sphere in 1956 as people were emboldened by Khrushchevs disparagement of Stalins practice of labeling critics as enemies.